| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

A DIFFERENT WAR: Marines in Europe and North Africa by Lieutenant Colonel Harry W. Edwards, U.S. Marine Corps (Ret) Assignment to London It is interesting to note that, when the 1st Provisional Brigade went ashore at Reykjavik, Iceland, it was met on the dock by Major Walter I. Jordan and members of his 12th Provisional Marine Company. These 11 Marines were survivors of the torpedoing and sinking of the Dutch transport, SS Maasdam, by a German submarine 300 miles south of Iceland on 26 June. They were rescued and taken to Iceland on the SS Randa. The men had formed an advance detail of Major Jordan's unit, en route from the Marine Barracks in Washington for assignment in London. Reembarked on the SS Volendam, they finally reached London on 15 July, there to join forces with 48 other Marines, including three officers, Captain John B. Hill and First Lieutenants Roy J. Batterton, Jr., and Joseph L. Atkins. These three officers had been embarked on another Dutch transport, the SS Indraporia, which made the crossing without mishap. The 59-man organization was designated the Marine Detachment, American Embassy. A second echelon arrived about six months later. The table of organization for this detachment had been prepared in London sometime earlier by Major John C. McQueen, at the request of Admiral Robert L. Ghormley, Assistant Chief of Naval Operations, who was in England at the time.

Major McQueen had been sent to London in the prewar period in 1940. He traveled in civilian clothes on a ship, Duchess of Richmond, and arrived in London during a German air raid. After reporting to the American Embassy, he went to Inveraray, Scotland, to observe the training of Royal Marines and especially to study the landing craft in use by the British. Marine Major Arthur T. Mason accompanied McQueen on this visit. Mason benefited from these contacts in his subsequent duty assignment to the combined operations section on the staff of the Supreme Commander Southeast Asia, Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten. While McQueen was in London, he was concerned about the lack of security at the American Embassy at 1 Grosvenor Square and made some comments to that effect. The American Ambassador, John Winant, was so impressed that he gave McQueen the job of embassy security officer.

Before leaving to return to Washington, he was entrusted with a classified instrument to be delivered to the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI). He had some anxious moments en route home through the Azores, since it was considered to be a den of spies at that time. Upon arrival in New York, he was met, unexpectedly, by strangers in civilian clothes. He thought surely they were out to waylay him, only to learn that they were ONI security men. He was relieved when he delivered his precious cargo to Washington: a top-secret radar device invented by the British and specifications for its manufacture. It was greatly superior to equipment then in development in the United States. McQueen was but one of a succession of Marine officers ordered to London during this period before the war and continuing throughout the war. Most of them held the title of "assistant naval attache" (ANA) or "special naval observer" (SNO). The ANA designation enabled one to travel on a diplomatic passport and to enjoy many of its privileges, including immunity from arrest in the host country. An attache was a member not only of the official staff of the American Ambassador to Great Britain, but also of the diplomatic corps, composed of all of the foreign governmental representatives resident in London. An attache also could be accredited to the London embassy while being designated as ANA in other countries. This was the case with several Marine officers, who were accredited to London and assigned to Cairo and other capitals. Once established in London, the Marine Detachment, American Embassy, under command of Major Walter I. Jordan, with Captain John B. Hill as executive officer, became the official reporting echelon for nearly all Marine personnel serving in Europe and Africa, including those on temporary duty and those attached to the OSS. The detachment was billeted at 20 Grosvenor Square, which was known at that time as the American Embassy Annex. Major Jordan and Captain Hill both held the title of ANA and their duties took them to various parts of the United Kingdom as Special Naval Observers (SNOs). Jordan was the only detachment commander to carry this added title. None of the three officers who succeeded him in the post — Captain Thomas J. Myers, First Lieutenant Alan Doubleday, and Captain Harry W. Edwards — were so designated.

Initially, the detachment roster showed a strength of four officers and 55 enlisted men. Since this was the first embassy detachment in London for the Marine Corps, the enlisted personnel were selected with emphasis on intelligence and military bearing; many of them had previously served in the 1939 World's Fair Detachment in New York. When the second echelon of the 12th Provisional Marine Company arrived in December 1941 with 2 more officers and 62 enlisted Marines, the strength swelled to 123. The two additional officers were Captain Walter Layer and First Lieutenant Thomas J. Myers. Before departure from America, all members of the detachment were outfitted with a complete civilian wardrobe, purchased from the Hecht Company in Washington, D.C., with a government clothing allowance. It was U.S. policy, prior to the declaration of war, to have military personnel travel in civilian clothes when en route to countries which were at war. The mission of the London detachment was to provide security for the American Embassy and to furnish escorts for State Department couriers. Sergeant John H. Allen, Jr., was assigned duty as orderly to the American Ambassador. The unit's billet on Grosvenor Square was close to the American Embassy, a very prestigious address in peacetime, but a tempting target in wartime. The Marines established their own mess, appointed an air raid precaution officer and, with the arrival of Harley-Davidson motorcycles equipped with sidecars, operated a courier service between the Embassy and various governmental staff offices in London. Warrant Officer George V. Clark organized the service, modeled after one that he operated in Shanghai, China, for the 4th Marines during 1937-1939. As with all services, the immediate prewar era was a period of rapid expansion for the Marine Corps. Marine aviation, which would grow from 240 pilots in 1940 to 10,000 in 1944, focused much of its attention on the Royal Air Force (RAF), whose effective air defense in the Battle of Britain (1940) was one of the greatest military victories of all time. It had severely reduced the strength and combat efficiency of the Luftwaffe, the German air force, saved the beleaguered survivors of Dunkirk, and protected England from invasion. Many Marine aviators visited England and Egypt during this time, and what they learned from the RAF would have a profound effect upon the development of tactics and techniques employed by the Marine air arm during World War II.

Major General Ralph J. Mitchell, Director of Aviation at Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, prior to World War II, was eager to have his officers and NCOs learn what they could from the British experience of fighting the Luftwaffe. He sent them as observers to Cairo and London and frequently as students or trainees to various training courses offered by the British.

These practices began before America entered the war, and continued throughout the war. Most of those officers were given the status of ANA for Air, and assigned to the American Embassy in London. After June 1941, they were carried, for record purposes, on the muster rolls of the Marine Detachment in London. Among the first arrivals, in April 1941, were Colonels Roy S. Geiger and Christian F. Schilt. They spent their time in Africa, observing British operations. Geiger was on board the British aircraft carrier Formidable while it was performing escort duty. By the time the carrier had reached its destination, it had lost all of its aircraft and pilots in combat operations protecting the convoy from attack by aircraft and submarines. Brigadier General Ross E. Rowell and Captain Edward C. Dyer took the long trip around through China and India and arrived in Cairo a month later. Rowell was interested in the operational side of the RAF and he told Dyer to concentrate on the technical aspects, since Dyer was a communications specialist with an advanced electronics degree and had been assigned to the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics. They met with top British military leaders: General Sir Archibald Wavell, Air Vice Marshal Arthur Tedder, and Admiral Andrew Cunningham, and found all of them extremely cooperative. In anticipation of American entry into the war, nearly all of the British commanders were very friendly and forthcoming with their military visitors. The only exception was General Bernard L. Montgomery, who had a reputation for not tolerating visitors at his headquarters.

The Marines were favorably impressed by a number of things which they observed, including: the organization of the war rooms; the RAF radio intercept system used to track the movement of all German aircraft; deceptive use of dummy airfields, complete with dummy aircraft; the competence of British radio technicians and their ingenuity in salvaging material for operational repairs; and the effective air defense system employed by the RAF in the Western Desert. Other Marine aviators who arrived in Cairo at this time included Lieutenant Colonels Claude A. Lar kin and Walter G. Farrell, and Captain Perry O. Parmalee. All visited RAF squadrons in Haifa and Beirut as well as Egypt. While in Egypt, Dyer contracted yellow jaundice and dengue fever and was to be hospitalized for a month. Once recovered, he caught up with Rowell in London, where they visited the RAF Coastal Command headquarters in Scotland and Bomber Command in England. They observed how the RAF used pathfinder aircraft to guide their bomber formations over German targets and how they employed saturation bombing to minimize losses. Dyer enrolled in a three-week course for fighter controllers at Stanmore where, for the first time, he was given detailed information about the use of radar. The Germans, as did the U.S., also had some radar equipment, but it was not nearly as sophisticated, or effective, as that developed by the British. Dyer next attended a British radar school and stood watches, as an observer, at various Fighter Command stations and ground control intercept stations, so as to become well indoctrinated in the system. For his return home, Dyer embarked on a British aircraft carrier and that was, for him, the most disappointing part of the entire trip. He alleged that the British use of alcohol in their wardrooms adversely affected both their personnel and their flight operations. Drawing upon his training and observations in England, Dyer was able to suggest changes in Marine aviation doctrine for employing intercepting aircraft more effectively. He also was able to adopt much of the RAF system of night interception in the subsequent development of training for night fighter squadrons in the Marine Corps. Back in Washington, he shared his knowledge with others, especially his Naval Academy classmate, Major Frank H. Schwable, who later played a large role in developing a night-fighter program for the Marine Corps.

Dyer's visit to England was quickly followed by those of other Marine flyers in 1941 and 1942. They included Schwable and Major Lewis G. "Griff" Merritt. Schwable was directed by the Commandant of the Marine Corps to "get all the information you can on the organization and operation of night fighting squadrons, paying particular attention to the operational routine, squadron training, gunnery and tactical doctrine..." He also was told not to be concerned about the technical end of it, since that had been covered by Dyer. Schwable and Merritt also visited Cairo to observe British air operations in desert warfare. When Schwable returned home in April 1942, he wrote a detailed report on his findings. He was convinced that the most essential qualification for a night fighter pilot was his desire to be one. He recommended that those selected should be fairly young but stable and conscientious, cool headed but aggressive, and not quick-on-the-trigger or devil-may-care, as many a day fighter had been.

He and Dyer fought hard to obtain funding for the aircraft and personnel that would ultimately produce an effective night fighter capability for the Marine Corps. When the first Marine Night Fighter Squadron, VMF(N)-531, was commissioned on 16 November 1942, Schwable became its leader and it would achieve a fine combat record in the Pacific war. The list of Marine aviators who visited Europe and North Africa operations continued. Lieutenant Colonel Francis P. Mulcahy and Major William J. Manley both spent nearly all of their time in Egypt. Lieutenant Colonel Field Harris and Major William D. McKittrick spent nearly four months, from August to November 1941, inspecting British aircraft facilities and equipment (much of which was American-made), debriefing bomber crews, and talking with staff officers. They also visited Palestine, Syria, and Cyprus. Captain Etheridge C. Best went to England to study the communications control system in the RAF. He attended the RAF Day Fighter Controller Course and several courses regarding radar. He also visited most of the RAF units in England. Returning home in early 1942, he helped to pioneer the use of a ground control intercept system by the Marine Corps and became a deputy director of the Electronics Division of the Bureau of Aeronautics. Prodded by an urgent request from Admiral William F. Halsey for a night fighter capability in the Pacific, the Marine Corps continued to send aviation personnel to England to observe and train with the RAF in order to learn its system of night fighting and radar control. Among the officers so assigned were Majors Frank H. Lamson-Scribner, William Via, Michael Sampas, Gooderham L. McCormick, Frank G. Dailey, and John Wehle.

Major Wehle, who was a Marine test pilot, took particular interest in testing various British aircraft. He was also charged to investigate the British glider program. He returned to the U.S. with a negative recommendation, which probably helped to doom a Marine Corps glider program that was already underway. Many distinguished ground officers also conducted productive visits to England as observers prior to America's entrance into the war. Colonel Julian C. Smith and Major Jack P. Juhan arrived in London at the height of the German air blitz and spent some anxious moments in air-raid shelters. They collected a large amount of material on landing boats and tactics, enjoyed a number of high-level briefings, and toured the British amphibious warfare base at Rosneath, Scotland, where they had a visit with Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill. Their trips were followed by those of Colonel John T. Walker, Majors George F. Good, Jr. and Lyman G. Miller, Captains Bruce T. Hemphill, Eustace C. Smoak, Joe Smoak, and Charles Cox, and Warrant Officer Ira Brook. During May and June of 1941, Major Good and Captain Hemphill traveled to England on a secret mission, along with some Navy civil engineers, to tour four base sites, two in Scotland and two in Ireland, and to advise the Marine Corps and the Navy as to their security requirements. They arrived in London on a Pan American Airways Clipper flight via Lisbon. Their itinerary included a five-day stay in Londonderry, Northern Ireland, followed by a stop in Greenoch, Scotland. At the end of their reconnaissance, Major Good returned to Iceland to rejoin the 5th Defense Battalion, and Captain Hemphill escorted the newly arrived Marine embassy guard detachment to London before returning to Washington. Majors Wallace M. Greene, Jr., and Samuel B. Griffith II, arrived together in England in 1941 with an interest in special forces, in anticipation of the establishment of similar organizations in the Marine Corps. Greene attended the British Amphibious Warfare School and the Royal Engineers' Demolition School, while Griffith observed commando training. After their return — and based to a degree upon an impetus from the White House — Major General Thomas Holcomb, Commandant of the Marine Corps, authorized the formation of two raider battalions. Griffith became the executive officer of the 1st Raider Battalion and subsequently its commander. The concept of having specialized units in the Marine Corps was a controversial issue and would continue to be so during the war. Commando training, however, was a focus of interest as the Marines noted the success the British commandos had, and they welcomed the opportunity to send Marines to England for that training. On 7 June 1942, the London detachment designated two of its officers, Captain Roy T. Batterton, Jr., and Marine Gunner George V. Clark, and 10 enlisted men, to take the training. Captain Batterton later provided some interesting highlights of his experience during seven grueling weeks that summer (He considered the course to have been extremely valuable to him during his subsequent duty with the 4th Marine Raider Battalion in the Pacific.).

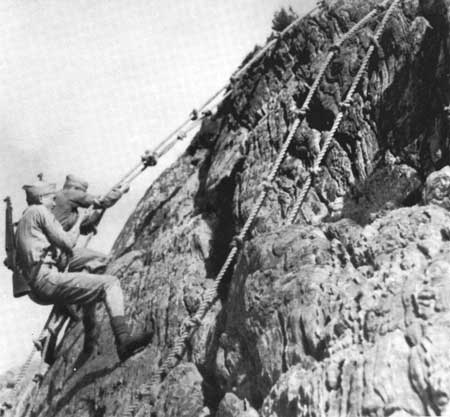

Batterton's Marine detail was assigned successively to four different commando units for its training at various bases in Scotland and England. Three were British Army Commandos (4th, 6th, and 9th) and one Royal Marines. A British Army commando averaged 500 men in size with a lieutenant colonel in command. There were six troops per commando, each commanded by a captain, and three sections per troop, each commanded by a lieutenant. Their training began at Achnacarry, Scotland, where the Marines were quartered in Nissen huts. Their beds consisted of wooden slabs, laid across six-inch blocks with straw mats as mattresses. Their working day was from 0830 to 1740, with time off only on Saturday afternoons. Training was in 40-minute periods allocated as follows: Bren gun, 16 periods; Thompson sub-machine gun, 4; grenades, 9; pistol, 4; foreign arms, 6; Garand rifle, 10; firing all weapons, 20; physical training, 21; bayonet, 6; climbing, 4. In addition, there were various course exercises, toggle bridging, field craft (scouting and patrolling), marching, map-reading, and two field exercises of 16 and 36 hours each. A rapid, seven-mile march demanded the utmost endurance. On such a forced march, the British required that all men keep in step, all the time, at either quick- or double-time, to create the teamwork which is essential to achieving their objective. On a toggle ride (called "Death Ride"), they crossed a stream by climbing a tree with the help of a 50-foot rope ladder, then sliding down a taut rope stretched downward at a 30-degree angle from the tree to another on the opposite bank, by looping the toggle rope over the taut rope. A toggle rope is normally six feet long and half an inch in diameter, with a wooden handle spliced on one end and an eye spliced on the other end. For descending from cliffs, they were taught a method called "absailing," which involves the use of a 100-foot length of 1/2-inch rope, looped first around a tree or a rock. The descent is made in bounds, and the rope section is brought along with each increment of descent. In an assault exercise, performed in 10 minutes, they crawled under a barbed wire, ascended a log ramp in order to jump from an eight-foot height over a six-foot barbed wire obstacle, descended a cliff by rope, and finished with a bayonet charge!

In another such exercise, two-man teams were employed, one covering the other, to approach a dummy house while firing from the hip with automatic weapons, throwing grenades through the windows, searching the structure, then departing over a fence, down a ravine by rope ladder, and up the other side by rope, using grenades against surprise targets, and ending with a bayonet charge. They also practiced rowing a 30-foot whaleboat, followed by a cross-country run of two miles from and back to the boat. Several of these assault exercises were conducted with live ammunition. The training schedule proceeded regardless of weather, which is frequently poor in Scotland. During training hours in the camp area, with few exceptions, everyone moved on the double. For their 36-hour exercise, they embarked for a night landing on a simulated Norwegian coastal area. Upon landing they moved 15 miles to a viaduct, made preparations to "blow it up;" and returned by a different route which was 35 miles cross-country. They organized a defensive perimeter and signaled for a retrieval by boat.

During the course of the seven weeks of training, the Marines went from Achnacarry, Scotland; to Cowes on the Isle of Wight; to Portsmouth, England (where they embarked in preparation for a landing at Dieppe on the French coast); then back to Scotland to Lachailort and Helensburgh. Thereafter, it was a tired but physically fit, well-trained detail of Marines which returned to its detachment in London on 31 July. These Marines were soon transferred to the United States and assigned to combat units for duty in the Pacific, mostly to Marine raider battalions in which they could practice and share their lessons learned. The senior British instructor was so pleased with the performance of this group that he sent a letter via Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, then head of British combined operations, to Admiral Stark at the headquarters of Commander, Naval Forces Europe, stating that "the Marines have undergone an arduous commando training with an exceptionally unconquerable spirit which never wavered during the course!" He singled out for special praise the work of Captain Batterton and Marine Gunner Clark and three NCOs: Platoon Sergeant Way Holland, and Sergeants George J. Huddock and Curtis A. Tatum. This report pleased Major Jordan, as he had been instrumental in organizing an exchange of training between the Royal Marines and the Corps which would continue over the years. Captain Batterton and his detail were not the first group of Marines to receive this commando training, nor were they the last. It proved to be a beneficial training resource for the Marine Corps in the early stages of World War II. During May and June 1941, Major Gerald C. Thomas and Captain James Roosevelt followed one of the most interesting itineraries of any Marine in the European Theater. On a special mission for President Roosevelt, they flew from India to Basra, Iraq, along with Brigadier William Slim of the British Army, arriving at a hotel that was filled with wounded soldiers. They flew from there on a British Sunderland flying boat to Suez, and on by car to Cairo, where they met two more Marine observers, Farrell and Captain Parmalee. After a briefing by the staff of Air Vice Marshal Arthur Tedder (later General Eisenhower's top deputy in Europe), they had a visit with General Sir Archibald Wavell, Middle East commander. Thereafter, they obtained requested transportation to Crete to deliver a message to King George, who had been driven from his throne in Greece by the Germans. Despite dire warnings of danger, they flew in a British flying boat to Crete, where they landed in the midst of a German air raid. Nevertheless, they completed their mission, which was to deliver the letter from President Roosevelt to King George, and then departed for Alexandria, Egypt. From Cairo they flew to Jerusalem for visits with King Peter of Yugoslavia; the High Commissioner for Palestine, Sir John McMichael; and Abdul, the Regent of Iraq. They were nearly killed here during a strafing attack by German fighters. They had only sandbags for protection, since there were no dugouts to hide in because of the high water table in the area. By the time they returned to Cairo, the Germans had already invaded Crete and seized the island with heavy losses for the British defense force. Returning to Cairo, they visited General Charles de Gaulle at his Free French Headquarters, then in Cairo, before leaving (along with Parmalee and Farrell) on a flying boat for Lisbon. Then-Captain Mountbatten also was a passenger on that flight. He had earlier lost his destroyer division in the battle of Greece, and he told them that his nephew, Prince Philip, was also a survivor of that action. At the end of that memorable trip, Major Thomas reported to the Commandant of the Marine Corps and requested to be returned to duty with troops. General Franklin A. Hart, USMC By the time Colonel Franklin A. Hart arrived for duty in London in June 1941, he already had a distinguished record of Marine Corps service.

A student at Auburn University, class of 1915, Hart was a top athlete in football, track, and soccer. He served as a Marine officer in France in World War I, and later in the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua, followed by a tour of sea duty and another of shore duty in Hawaii. As a Special Naval Observer in England during World War II, he participated in the Dieppe operation in July 1942 and remained in England until October on the ComNavEu staff. In June 1943 he commanded the 24th Marines in the Marshall Islands and at both Saipan and Tinian, from which operations he earned the Navy Cross and the Legion of Merit. As assistant division commander of the 4th Marine Division on Iwo Jima, he received a Bronze Star Medal. Subsequent duty assignments included: Director, Division of Reserve, and Director, Public Information, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps; and Commanding General, Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island. After his last command as Commandant, Marine Corps Schools, Quantico, Lieutenant General Hart retired in 1954 and was promoted to general on the retired list. He died on 22 June 1967. The muster rolls of the Marine Detachment in London frequently included the names of "visiting" Marines. The number of visitors each month varied, as did their assignments and missions. In this category, OSS Marines were a most unusual group, mostly reservists recruited because they possessed highly specialized skills needed to carry out the organization's intelligence mission. The OSS was established on 13 June 1942 as a successor to the Office of the Coordinator of Information (COI). Its director was Army Reserve Colonel William J. Donovan, a World War I hero and recipient of the Medal of Honor, whose reputation for fearlessness earned him the nick name of "Wild Bill!" OSS was a strategic intelligence organization which functioned outside the military services to carry out missions assigned by the chiefs of the armed services.

In addition to its civilian personnel, OSS had the authority to recruit military personnel from all services. Marine officers assigned to this work were given a specialty of MSS: Miscellaneous Strategic Services. More than 35 Marine officers and a considerable number of enlisted Marines were assigned to duty with the OSS in Africa and Europe during the war. Their duties were so highly secret that even their award citations were classified and remained so until after the war. Captain Peter J. Ortiz, for example, was twice awarded the Navy Cross, but these citations were not immediately published. The Marine Corps personnel in OSS made significant contributions to the Allied war effort in Europe and throughout the world.

In October 1942, two COI/OSS Marines were stationed at the American Legation in Tangiers, Morocco, a key listening post in Africa for the U.S. at the time. They were Lieutenant Colonel William A. Eddy and Second Lieutenant Franklin Holcomb. Eddy was born in Lebanon of American missionary parents and was fluent in Arabic. He had earned a Navy Cross and two Silver Star Medals for combat action with the 6th Marines in World War I. Holcomb was the only son of the Marine Corps Commandant, General Holcomb. Both officers were designated assistant naval attaches for air and would play a prominent role in relations with the Vichy French, and in providing valuable intelligence for Allied landings in Africa. Robert D. Murphy, counselor of the American Embassy in Vichy, once commented that "no American knew more about Arabs or power politics in Africa than Colonel Eddy." In January 1943 they were joined in Tangier by Captain Ortiz. He was an American citizen but had served in the French Foreign Legion early in World War Il. Thus, he was well acquainted with the area.

Marine Reserve Lieutenant Otto Weber also received an unusual assignment. A petroleum specialist as a civilian, he was ordered, under the auspices of the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), to report for duty in Cairo. From there he went to Asmara, Eritrea, where he stayed for several months, and finally he returned to Cairo and served as an intelligence officer with the Army Forces in the Middle East. Colonel Peter J. Ortiz, USMC One of the most decorated Marine officers of World War II, Colonel Peter Ortiz served in both Africa and Europe throughout the war, as a member of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Although born in the U.S., he was educated in France and began his military service in 1932 at the age of 19 with the French Foreign Legion. He was wounded in action and imprisoned by the Germans in 1940. After his escape, he made his way to the U.S. and joined the Marines. As a result of his training and experience, he was awarded a commission, and a special duty assignment as an assistant naval attache in Tangier, Morocco. Once again, Ortiz was wounded while performing combat intelligence work in preparation for Allied landings in North Africa. In 1943, as a member of the OSS, he was dropped by parachute into France to aid the Resistance, and assisted in the rescue of four downed RAF pilots. He was recaptured by the Germans in 1944 and spent the remainder of the war as a POW. Ortiz's decorations included two Navy Crosses, the Legion of Merit, the Order of the British Empire, and five Croix de Guerre. He also was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor by the French. Upon return to civilian life, Ortiz became involved in the film industry. At the same time, at least two Hollywood films were made based upon his personal exploits. He died on 16 May 1988 at the age of 75.

As a result of the lend-lease to the Royal Navy of 50 overage destroyers early in the war, the British made available to the United States bases on various islands in the Atlantic. Marine units were posted at several of these naval bases, where they remained throughout the war. They included: Marine Barracks in Bermuda, Trinidad, and Argentia, Newfoundland, and Marine detachments on Grand Cayman and Antigua islands and in the Bahamas. As a result of the lend-lease to the Royal Navy of 50 overage destroyers early in the war, the British made available to the United States bases on various islands in the Atlantic. Marine units were posted at several of these naval bases, where they remained throughout the war. They included: Marine Barracks in Bermuda, Trinidad, and Argentia, Newfoundland, and Marine detachments on Grand Cayman and Antigua islands and in the Bahamas.

|