|

Popular Study Series History No. 14: American Charcoal Making |

|

American Charcoal Making*

In the Era of the Cold-blast Furnace

By Jackson Kemper, III, Formerly Research Assistant, French Creek Recreational Demonstration Area, Birdsboro, Pennsylvania.

[HOPEWELL Village National Historic Site, Pennsylvania, contains a 170-year-old cold-blast furnace which was one of the last of its type to compete with anthracite-fueled hot-air furnaces. When it, with others of its kind, gave way before the new processes that were destined to contribute vitally to the development of America's great iron industry, a final chapter was written into the record of a companion technique—the making of furnace charcoal. Aware that an abandoned art eventually might become a completely lost one, the National Park Service provided a demonstration revival of the obsolescent method so that accurate textual and photographic data could be obtained for permanent record. Supervised by octogenarian Lafayette Houck, last of the Hopewell colliers, all steps of the coaling process of an earlier day were reenacted while Mr. Kemper stayed night and day at the site of operations and assembled the information which follows. Ed.]

Lafayette Houck, Hopewell's last collier. |

Two and a half centuries ago the Schuylkill Valley in Pennsylvania, which extends from the present coal region to the city of Philadelphia, was an untouched wilderness. The section was not only rich in metal and water power but possessed also a great wealth of timberland which later became the first source of charcoal fuel for the great iron industry to come.

The first colonists to discover the rich valley were a group of Swedish people who had settled on the Delaware River in 1638. They went up the Schuylkill by canoe and found a livelihood in trading with the Indians, fishing for shad, and cultivating the rough but fertile lands. In 1681 William Penn received his charter and grant from Charles II of England in consideration of a debt of £16,000 due to his father. With Penn came the great influx of English, Welsh, Dutch, and German settlers to what later was the Province and State of Pennsylvania.

Early colonial writers often mentioned rumors that there was iron ore in the Schuylkill Valley, and Penn himself encouraged the belief. It was not until 1716, however, that steps were taken to transform into pig iron the great natural resources of ore, water power, and timber. It was in that year that Thomas Rutter, who had been in business as a blacksmith near Germantown as early as 1682, moved up the river and constructed in the vicinity of what now is Pottstown the first bloomery forge of the province. The great ore beds, the thick woodlands assuring tremendous reserves of charcoal, and the bold streams promising water power soon induced many capable and hopeful men to follow Rutter's lead in the attempt to make iron. Between 1716 and 1771 more than 50 forges and furnaces are known to have been constructed in the province; and there probably were countless others.

By 1719 Rotter was convinced that his experiment at the mouth of the Manatawny could be developed into a great industry. Accordingly, with his friend Thomas Potts, and with the support of others, he began to build Colebrookdale, the first charcoal furnace in the province. It is interesting that the first charcoal furnace in England to cast hollow ware by the use of sand molds also was called Colebrookdale.

So much jealousy was excited in England by the excellent quality of the ironware produced in the American colonies and shipped to the mother country that in 1719 a bill was introduced in Parliament to prevent the construction of rolling and slitting mills here. The bill was rejected but the news that the colonies could produce good metal spread quickly and aroused the enthusiasm of many enterprising young men.

William Bird, whose exact antecedents are not known, came to Pennsylvania a year or two before 1728 and soon was recognized as a contemporary with Rutter, Potts, Samuel Savage, and Samuel McNutt in the establishment of forges and furnaces. When Rutter's will was admitted to probate in Philadelphia, November 27, 1728, Bird was a witness. He then was a resident of Amity township, a part of Philadelphia County, and at the age of 23 had attained a position of influence in his community, serving as a commissioner in the laying out of public roads. By 1733 he was working at Pine Forge as a woodchopper earning 2 shillings 8 pence a cord, and a few years later he rented a one-eighth share in the forge at £40 a year. At about that time he began to acquire property for his own enterprises west of the Schuylkill and in the vicinity of Hay Creek. He started construction of the Hopewell forge in the fall of 1743 and was handling pig iron as early as March of the next year.

Upon the death of William Bird in 1761, forges at Birdsboro and Hopewell passed to his son, Mark Bird, who took over the management of the family business at the age of 22. Upon discovering a rich ore vein near the Hopewell forge, he built a furnace there in 1770, "or a year or two before." With the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, he answered the call of the new country and, as a lieutenant colonel in a regiment of Berks County volunteers, took command of his battalion and equipped it with his personal funds.

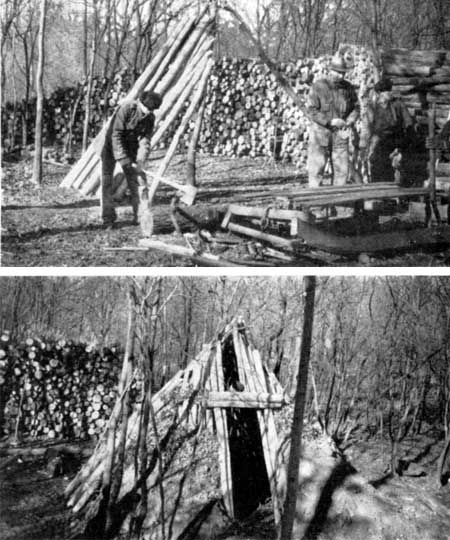

A typical collier's hut. |

At the height of Mark Bird's prosperity the ironmaster believed himself immune to disaster. "Neither fire nor flood can harm me," an expression of his, was quoted for many years in the community. He was held in high esteem, and welcomed everywhere with the utmost cordiality. He was wont to create an impression when he arrived from Philadelphia in his coach drawn by four handsome horses. Yet both flood and fire visited him. His vast holdings, spread into several counties of Pennsylvania and into New Jersey and Virginia, suffered from neglect during the war, and his personal means dwindled considerably as a result of his patriotic generosity. The end came in 1788 when he was "sold out" by the sheriff to satisfy various bonds.

With the Hopewell furnace as the center of activity, a little feudal village had gradually developed consisting of the "Big House," where the owner or manager lived, and the many tenant houses for the families of the furnace men, colliers, woodchoppers, molders, miners, teamsters, blacksmiths, wheelwrights, and others. The company store supplied every need of the village inhabitants from food to clothing, while a one-room schoolhouse gave to the younger generation the fundamentals in reading, writing, and arithmetic. A large farm and garden also were operated and maintained by the owner of the furnace to supply the community with much of the foodstuff and to provide hay enough for each family to keep a cow in an adjoining "one-cow" stable.

The lady of the Big House was looked upon as the mistress of the community. When anyone became ill or needed help in any way, she was the first person to be called in and consulted. Social activities at the Big House were festive occasions, particularly at Christmas and New Year's when the entire village took part.

Until 1837 charcoal was the only fuel which could be used successfully in the cold-blast furnace. Many attempts were made between 1815 and 1838 to use the recently discovered anthracite coal, but the experiments generally were unsatisfactory because the heat generated was insufficient to melt the ore. Then James B. Neilson of Scotland obtained a patent for the use of hot air in the blast. On February 7, 1837, George Crane was successful in smelting iron at his works in Ynyscedivin, Wales, by using Neilson's hot air blast on anthracite coal and producing 36 tons a week. In May of that year, Solomen W. Roberts of Philadelphia visited Crane's works in Wales and witnessed the satisfactory results obtained from the method. Upon his return to the United States, he made recommendations which resulted in organization of the Lehigh Crane Iron Company to manufacture pig iron with anthracite coal of the Lehigh Valley. This is believed to have been the first successful furnace of its kind in the country.

Collier's hut under construction. |

The reason that ironmasters of the nineteenth century wished to convert their cold-blast charcoal furnaces into hot-blast anthracite furnaces was based primarily on economic grounds. The maintenance of great wood tracts and the expense of labor for making the wood into charcoal were tremendous items. The use of anthracite coal not only obviated these factors but also brought the industry out of the wilderness, so to speak, and into the cities where product and market were in closer proximity.

It is due to this economic stage in the evolution of the great iron industry of Pennsylvania that the old art of making charcoal has been forgotten. Hopewell furnace remained a cold-blast charcoal furnace to its final blast and was one of the last works of its kind to attempt modern competition.

*From The Regional Review, National Park Service, Region One, Richmond, Va., vol. V, no. 1, July 1940, pp. 3-14.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Oct 20 2001 10:00:00 am PDT |