| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

THE FINAL CAMPAIGN: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) L-Day and Movement to Contact Operation Iceberg got off to a roaring start. The few Japanese still in the vicinity of the main assault at first light on L-Day, 1 April 1945, could immediately sense the wisdom of General Ushijima in conceding the landing to the Americans. The enormous armada, assembled from ports all over the Pacific Ocean, had concentrated on schedule off Okinawa's southwest coast and stood coiled to project its 182,000-man landing force over the beach. This would be the ultimate forcible entry, the epitome of all the amphibious lessons learned so painstakingly from the crude beginnings at Guadalcanal and North Africa. Admiral Turner made his final review of weather conditions in the amphibious objective area. As at Iwo Jima, the amphibians would be blessed with good weather on the critical first day of the landing. Skies would be cloudy to clear, winds moderate east to northeast, surf moderate, temperature 75 degrees. At 0406 Turner announced "Land the Landing Force," the familiar phrase which marked the sequential countdown to the first assault waves hitting the beaches at H-Hour. Combat troops already manning the rails of their transports then witnessed an unforgettable display of naval power — the sustained bombardment by shells and rockets from hundreds of ships, alternating with formations of attack aircraft streaking low over the beaches, bombing and strafing at will. Enemy return fire seemed scattered and ineffectual, even against such a mass of lucrative targets assembled offshore. Turner confirmed H-Hour at 0830.

Now came the turn of the 2d Marine Division and the ships of the Diversionary Force to decoy the Japanese with a feint landing on the opposite coast. The ersatz amphibious force steamed into position, launched amphibian tractors and Higgins boats, loaded them conspicuously with combat-equipped Marines, then dispatched them towards Minatoga Beach in seven waves. Paying careful attention to the clock, the fourth wave commander crossed the line of departure exactly at 0830, the time of the real H-Hour on the west coast. The LVTs and boats then turned sharply away and returned to the transports, mission accomplished. There is little doubt that the diversionary landing (and a repeat performance the following day) achieved its purpose. In fact, General Ushijima retained major, front-line infantry and artillery units in the Minatoga area for several weeks thereafter as a contingency against a secondary landing he fully anticipated. The garrison also reported to IGHQ on L-Day morning that "enemy landing attempt on east coast completely foiled with heavy losses to enemy."

But the successful deception came at considerable cost. Japanese kamikazes, convinced that this was the main landing, struck the small force that same morning, seriously damaging the troopship Hinsdale and LST 844. The 3d Battalion, 2d Marines, and the 2d Amphibian Tractor Battalion suffered nearly 50 casualties; the two ships lost an equal number of sailors. Ironically, the division expected to have the least damage or casualties in the L-Day battle lost more men than any other division in the Tenth Army that day. Complained division Operations Officer Lieutenant Colonel Samuel G. Taxis: "We had asked for air cover for the feint but were told the threat would be 'incidental.'" On the southwest approaches, the main body experienced no such interference. An extensive coral reef provided an offshore barrier to the Hagushi beaches, but by 1945 reefs no longer posed a problem to the landing force. Unlike Tarawa, where the reef dominated the tactical development of the battle, General Buckner at Okinawa had more than 1,400 LVTs to transport his assault echelons from ship to shore without hesitation. These long lines of LVTs now extended nearly eight miles as they churned across the line of departure on the heels of 360 armored LVT-As, whose turret-mounted, snub-nosed 75mm howitzers blasted away at the beach as they advanced the final 4,000 yards. Behind the LVTs came nearly 700 DUKWs, amphibious trucks, bearing the first of the direct support artillery battalions. The horizon behind the DUKWs seemed filled with lines of landing boats. These would pause at the reef to marry with outward bound LVTs. Soldiers and Marines alike had rehearsed transfer line operations exhaustively. There would be no break in the assault's momentum this day.

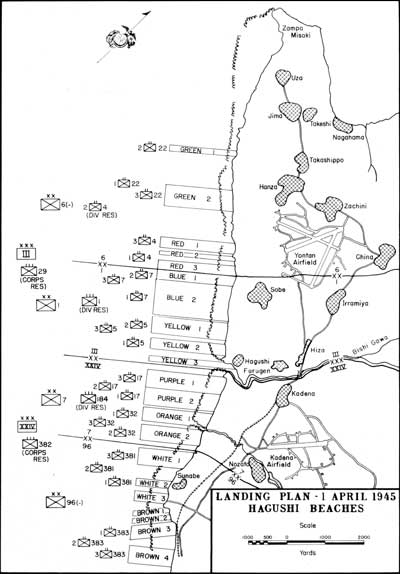

The mouth of the Bishi Gawa (River) marked the boundary between the XXIV Corps and IIIAC along the Hagushi beaches. The Marines' tactical plan called for the two divisions to land abreast, the 1st on the right, the 6th on the left. Each division in turn landed with two regiments abreast. The assault regiments, from north to south, were the 22d, 4th, 7th, and 5th Marines. Reflecting years of practice, the first assault wave touched down close to 0830, the designated H-Hour. The Marines stormed out of their LVTs, swarmed over the berms and seawalls, and entered the great unknown. The forcible invasion of Okinawa had begun. Within the first hour the Tenth Army had put 16,000 combat troops ashore. The assault troops experienced a universal shock during the ship-to-shore movement. In spite of the dire intelligence predictions and their own combat experience, the troops found the landing to be a cakewalk — virtually unopposed. Private First Class Gene Sledge's mortar section went in singing "Little Brown Jug" at the top of its lungs. Corporal James L. Day, a rifle squad leader attached to Company F, 2d Battalion, 22d Marines, who had landed at Eniwetok and Guam earlier, couldn't believe his good luck: "I didn't hear a single shot all morning — it was unbelievable!" Most veterans expected an eruption of enemy fire any moment. Later in the day General del Valle's LVT became stuck in a pothole enroute to the beach, the vehicle becoming a very lucrative, immobile target. "It was the worst 20 minutes I ever spent in my life," he said.

The morning continued to offer pleasant surprises to the invaders. They found no mines along the beaches, discovered the main bridge over the Bishi River still intact and — wonder of wonders — both airfields relatively undefended. The 6th Marine Division seized Yontan Airfield by 1300; the 7th Infantry Division had no problems securing nearby Kadena. The rapid clearance of the immediate beaches by the assault units left plenty of room for follow-on forces, and the division commanders did not hesitate to accelerate the landing of tanks, artillery battalions, and reserves. The mammoth build-up proceeded with only a few glitches. Four artillery pieces went down when their DUKWs foundered along the reef. Several Sherman tanks grounded on the reef. And the 3d Battalion, 1st Marines, reached the transfer line by 1800 but had to spend an uncomfortable night in its boats when sufficient LVTs could not be mustered at that hour for the final leg. These were minor inconveniences. Incredibly, by day's end, the Tenth Army had 60,000 troops ashore, occupying an expanded beachhead eight miles long and two miles deep. This was the real measure of effectiveness of the Fifth Fleet's proven amphibious proficiency.

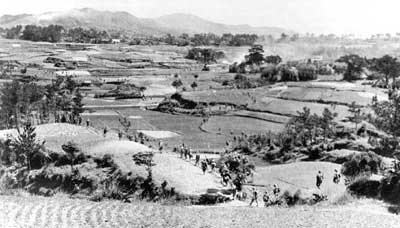

The huge landing was not entirely bloodless. Snipers wounded Major John H. Gustafson, commanding the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, late in the afternoon. Other men went down to enemy mortar and machine gun fire. But the losses of the entire Tenth Army, including the hard-luck 2d Marine Division, amounted to 28 killed, 104 wounded, and 27 missing on L-Day. This represented barely 10 percent of the casualties sustained by the V Amphibious Corps the first day on Iwo Jima. Nor did the momentum of the assault slow appreciably after the Tenth Army broke out of the beachhead. The 7th Infantry Division reached the East Coast on the second day. On the third day, the 1st Marine Division seized the Katchin Peninsula, effectively cutting the island in two. By that date, IIIAC elements had reached objectives thought originally to require 11 days in the taking. Lieutenant Colonel Victor H. Krulak, operations officer for the 6th Marine Division, recalls General Shepherd telling him, "Go ahead! Plow ahead as fast as you can. We've got these fellows on the run." "Well, hell," said Krulak, "we didn't have them on the run. They weren't there."

As the 6th Marine Division swung north and the 1st Marine Division moved out to the west and northwest, their immediate problems stemmed not from the Japanese but from a sluggish supply system, still being processed over the beach. The reef-side transfer line worked well for troops but poorly for cargo. Navy beachmasters labored to construct an elaborate causeway to the reef, but in the meantime, the 1st Marine Division demonstrated some of its amphibious logistics know-how learned "on-the-job" at Peleliu. It mounted swinging cranes on powered causeways and secured the craft to the seaward side of the reef. Boats would pull alongside in deep water; the crane would lift nets filled with combat cargo from the boats into the open hatches of a DUKW or LVT waiting on the shoreward side for the final run to the beach. This worked so well that the division had to divide its assets among the other divisions within the Tenth Army. Beach congestion also slowed the process. Both Marine divisions resorted to using their replacement drafts as shore party teams. Their in experience in this vital work, combined with the constant call for groups as replacements, caused problems of traffic control, establishment of functional supply dumps, and pilferage. This was nothing new; other divisions in earlier operations had encountered the same circumstances. The rapidly advancing assault divisions had a critical need for motor transport and bulk fuel, but these proved slow to land and distribute. Okinawa's rudimentary road network further compounded the problem. Colonel Edward W. Snedeker, commanding the 7th Marines, summarized the situation after the landing in this candid report: "The movement from the west coast landing beaches of Okinawa across the island was most difficult because of the rugged terrain crossed. It was physically exhausting for personnel who had been on transports a long time. It also presented initially an impossible supply problem in the Seventh's zone of action because of the lack of roads."

General Mulcahy did not hesitate to move the command post of the Tactical Air Force ashore as early as L plus 1. Operating from crude quarters between Yontan and Kadena, Mulcahy kept a close eye on the progress the SeaBees and Marine and Army engineers were making on repairing both captured airfields. The first American aircraft, a Marine observation plane, landed on 2 April. Two days later the fields were ready to accept fighters. By the eighth day, Mulcahy could accommodate medium bombers and announced to the Fleet his assumption of control of all aircraft ashore. By then his fighter arm, the Air Defense Command, had been established ashore nearby under the leadership of Marine Brigadier General William J. Wallace. With that, the graceful F4U Corsairs of Colonel John C. Munn's Marine Aircraft Group (MAG) 31 and Colonel Ward E. Dickey's MAG-33 began flying in from their escort carriers. Wallace immediately tasked them to fly combat air patrols (CAP) over the fleet, already seriously embattled by massed kamikaze attacks. Ironically, most of the Marine fighter pilots' initial missions consisted of CAP assignments, while the Navy squadrons on board the escort carriers picked up the close air support jobs. Dawn of each new day would provide the spectacle of Marine Corsairs taking off from land to fly CAP over the far-flung Fifth Fleet, passing Navy Hellcats from the fleet coming in take station in support of the Marines fighting on the ground. Other air units poured into the two airfields as well: air warning squadrons, night fighters, torpedo bombers, and an Army Air Forces fighter wing. While neither Yontan nor Kadena were ex actly safe havens — each received nightly artillery shelling and long-range bombing for the first full month ashore — the two airfields remained in operation around the clock, an invaluable asset to both Admiral Spruance and General Buckner.

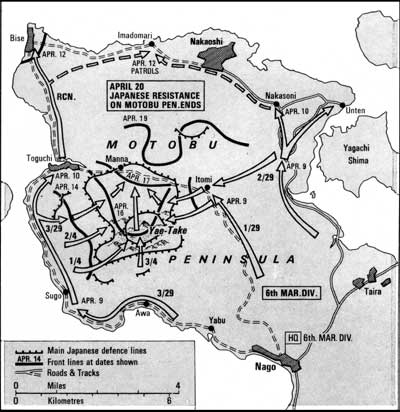

While the 1st Marine Division continued to hunt down small bands of enemy guerrillas and infiltrators throughout the center of the island, General Geiger unleased the 6th Marine Division to sweep north. These were heady days for General Shepherd's troops: riflemen clustered topside on tanks and self-propelled guns, streaming northward against a fleeing foe. Not since Tinian had Marines enjoyed such exhilarating mobility. By 7 April the division had seized Nago, the largest town in northern Okinawa, and the U.S. Navy obligingly swept for mines and employed underwater demolition teams (UDT) to breach obstacles in order to open the port for direct, sea-borne delivery of critical supplies to the Marines. Corporal Day marveled at the rapidity of their advance so far. "Hell, here we were in Nago. It was not tough at all. Up to that time [our squad] had not lost a man." The 22d Marines continued north through broken country, reaching Hedo Misaki at the far end of the island on L plus 12, having covered 55 miles from the Hagushi landing beaches. For the remainder of the 6th Marine Division, the honeymoon was about to end. Just northwest of Nago the great bulbous nose of Motobu Peninsula juts out into the East China Sea. There, in a six-square-mile area around 1,200-foot Mount Yae Take, Colonel Takesiko Udo and his Kunigami Detachment ended their delaying tactics and assumed prepared defensive positions. Udo's force consisted of two rifle battalions, a regimental gun company and an antitank company from the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade, in all about two thousand seasoned troops.

Yae Take proved to be a defender's dream, broken into steep ravines and tangled with dense vegetation. The Japanese sowed the approaches with mines and mounted 20mm dual purpose machine-cannons and heavier weapons deep within caves. As Colonel Krulak recalled: "They were just there — they weren't going anywhere — they were going to fight to the death. They had a lot of naval guns that had come off disabled ships, and they dug them way back in holes where their arc of fire was not more than 10 or 12 degrees." One of the artillery battalions of the 15th Marines had the misfortune to lay their guns directly within the narrow arc of a hidden 150mm cannon. "They lost two howitzers before you could spell cat," said Krulak. The battle of Yae Take became the 6th Marine Division's first real fight, five days of difficult and deadly combat against an exceptionally determined enemy. Both the 4th and 29th Marines earned their spurs here, developing teamwork and tactics that would put them in good stead during the long campaign ahead.

Part of General Shepherd's success in this battle stemmed from his desire to provide proven leaders in command of his troops. On the 15th, Shepherd relieved Colonel Victor F. Bleasdale, a well-decorated World War I Marine, to install Guadalcanal veteran Colonel William J. Whaling as commanding officer of the 29th Marines. When Japanese gunners killed Major Bernard W. Green, commanding the 1st Battalion, 4th Marines, Colonel Shapley assigned his own executive officer, Lieutenant Colonel Fred D. Beans, a former Marine raider, as his replacement. The savage fighting continued, with three battalions attacking from the west, two from the east — protected against friendly fire by the steep pinnacle between them. Logistic support to the fighting became so critical that every man, from private to general, who ascended the mountain to the front lines carried either a five-gallon water can or a case of ammo. And all hands coming down the mountain had to help bear stretchers of wounded Marines. On 15 April, one company of the 2d Battalion, 4th Marines, suffered 65 casualties, including three consecutive company commanders. On 16 April, two companies of the 1st Battalion, 4th Marines, seized the topographic crest. On the following day, the 29th Marines received exceptional fire support from the 14-inch guns of the old battleship Tennessee and low-level, in-your-pocket bombing from the Corsairs of Marine Fighter Squadron 322.

Colonel Udo and his Kunigami Detachment died to the man at Yae Take. On 20 April General Shepherd declared the Motobu Peninsula secured. His division had earned a valuable victory, but the cost had not been cheap. The 6th Marine Division suffered the loss of 207 killed and 757 wounded in the battle. The division's overall performance impressed General Oliver P. Smith, who recorded in his journal:

During the battle for Motobu Peninsula, the 77th Infantry Division once again displayed its amphibious prowess by landing on the island of Ie Shima to seize its airfields. On 16 April, Major Jones' force reconnaissance Marines again helped pave the way by seizing Minna Shima, a tiny islet about 6,000 yards off shore from Ie Shima. Here the soldiers positioned a 105mm battery to further support operations ashore. The 77th needed plenty of fire support. Nearly 5,000 Japanese defended the island. The soldiers overwhelmed them in six days of very hard fighting at a cost of 1,100 casualties. One of these was the popular war correspondent Ernie Pyle, who had landed with the Marines on L-Day. A Japanese Nambu gunner on Ie Shima shot Pyle in the head, killing him instantly. Soldiers and Marines alike grieved over Pyle's death, just as they had six days earlier with the news of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's passing.

The 1st Marine Division fought a different campaign in April than their sister division to the north. Their days were filled with processing refugees and their nights with patrols and ambushes. Guerrillas and snipers exacted a small but steady toll. The 7th Marines became engaged in a hot firefight near Hizaonna, but most of the action remained small-unit and nocturnal. The "Old Breed" Marines welcomed the cycle of low intensity. After so many months in the tropics, they found Okinawa refreshingly cool and pastoral. The Marines grew concerned about the welfare of the thousands of Okinawan refugees who straggled northwards from the heavy fighting. As Private First Class Eugene Sledge observed, "The most pitiful things about the Okinawan civilians were that they were totally bewildered by the shock of our invasion, and they were scared to death of us. Countless times they passed us on the way to the rear with fear, dismay, and confusion on their faces." Sledge and his companions in the 5th Marines could tell by the sound of intense artillery fire to the south that the XXIV Corps had collided with General Ushijima's outer defenses. Within the first week the soldiers of the 7th and 96th Divisions had answered the riddle of "where are the Japs?" By the second week, both General Hodge and General Buckner were painfully aware of Ushijima's intentions and the range and depth of his defensive positions. In addition to their multitude of caves, minefields, and reverse-slope emplacements, the Japanese in the Shuri complex featured the greatest number of large-caliber weapons the Americans had ever faced in the Pacific. All major positions enjoyed mutually supporting fires from adjacent and interior hills and ridgelines, themselves honeycombed with caves and fighting holes. Maintaining rigid adherence to these intricate networks of mutually supporting positions required iron discipline on the part of the Japanese troops. To the extent this discipline prevailed, the Americans found themselves entering killing zones of savage lethality.

In typical fighting along this front, the Japanese would contain and isolate an American penetration (Army or Marine) by grazing fire from supporting positions, then smother the exposed troops on top of the initial objective with a rain of preregistered heavy mortar shells until fresh Japanese troops could swarm out of their reverse-slope tunnels in a counterattack. Often the Japanese shot down more Americans during their extraction from some fire-swept hilltop than they did in the initial advance. These early U.S. assaults set the pattern to be encountered for the duration of the campaign in the south. General Buckner quickly committed the 27th Infantry Division to the southern front. He also directed General Geiger to loan his corps artillery and the heretofore lightly committed 11th Marines to beef up the fire support to XXIV Corps. This temporary assignment provided four 155mm battalions, three 105mm battalions, and one residual 75mm pack howitzer battalion (1/11) to the general bombardment underway of Ushijima's outer defenses. Lieutenant Colonel Frederick P. Henderson, USMC, took command of a provisional field artillery group comprised of the Marine 155mm gun battalions and an Army 8-inch howitzer battalion — the "Henderson Group" — which provided massive fire support to all elements of the Tenth Army. Readjusting the front lines of XXIV Corps to allow room for the 27th Division took time; so did building up adequate units of fire for field artillery battalions to support the mammoth, three-division offensive General Buckner wanted. A week of general inactivity passed along the southern front, which inadvertently allowed the Japanese to make their own adjustments and preparations for the coming offensive. On 18 April (L plus 17) Buckner moved the command post of the Tenth Army ashore. The offensive began the next morning, preceded by the ungodliest preliminary bombardment of the ground war, a virtual "typhoon of steel" delivered by 27 artillery batteries, 18 ships, and 650 aircraft. But the Japanese simply burrowed deeper into their underground fortifications and waited for the infernal pounding to cease and for American infantry to advance into their well-designed killing traps.

The XXIV Corps executed the assault on 19 April with great valor, made some gains, then were thrown back with heavy casualties. The Japanese also exacted a heavy toll of U.S. tanks, especially those supporting the 27th Infantry Division. In the fighting around Kakazu Ridge, the Japanese had separated the tanks from their supporting infantry by fire, then knocked off 22 of the 30 Shermans with everything from 47mm guns to hand-delivered satchel charges. The disastrous battle of 19 April provided an essential dose of reality to the Tenth Army. The so-called "walk in the sun" had ended. Overcoming the concentric Japanese defenses around Shuri was going to require several divisions, massive firepower, and time — perhaps a very long time. Buckner needed immediate help along the Machinato Kakazu lines. His operations officer requested General Geiger to provide the 1st Tank Battalion to the 27th Division. Hearing this, General del Valle became furious. "They can have my division," he complained to Geiger, "but not piece-meal." Del Valle had other concerns. Marine Corps tankers and infantry trained together as teams. The 1st Marine Division had perfected tank-infantry offensive attacks in the crucible of Peleliu. Committing the tanks to the Army without their trained infantry squads could have proven disastrous. Fortunately, Geiger and Oliver P. Smith made these points clear to General Buckner. The Tenth Army commander agreed to refrain from piece-meal commitments of the Marines. Instead, on 24 April, he re quested Geiger to designate one division as Tenth Army Reserve and make one regiment in that division ready to move south in 12 hours. Geiger gave the mission to the 1st Marine Division; del Valle alerted the 1st Marines to be ready to move south. These decisions occurred while Buckner and his senior Marines were still debating the possibility of opening a second front with an amphibious landing on the Minatoga Beaches. But the continued bloody fighting along the Shuri front received the forefront of Buckner's attention. As his casualties grew alarmingly, Buckner decided to concentrate all his resources on a single front. On 27 April he assigned the 1st Marine Division to XXIV Corps. During the next three days the division moved south to relieve the shot-up 27th Infantry Division on the western (right) flank of the lines. The 6th Marine Division received a warning order to prepare for a similar displacement to the south. The long battle for Okinawa's southern highlands was shifting into high gear. Meanwhile, throughout April and with unprecedented ferocity, the Japanese kamikazes had punished the ships of the Fifth Fleet supporting the operation. So intense had the aerial battles become that the western beaches, so beguilingly harmless on L-Day, became positively deadly each night with the steady rain of shell fragments from thousands of antiaircraft guns in the fleet. Ashore or afloat, there were no safe havens in this protracted battle.

|