| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

FIRST OFFENSIVE: The Marine Campaign for Guadalcanal by Henry I. Shaw, Jr. November and the Continuing Buildup While the soldiers and Marines were battling the Japanese ashore, a patrol plane sighted a large Japanese fleet near the Santa Cruz Islands to the east of the Solomons. The enemy force was formidable, 4 carriers and 4 battleships, 8 cruisers and 28 destroyers, all poised for a victorious attack when Maruyama's capture of Henderson Field was signalled. Admiral Halsey's reaction to the inviting targets was characteristic, he signaled Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, with the Hornet and Enterprise carrier groups located north of the New Hebrides: "Attack Repeat Attack." Early on 26 October, American SBDs located the Japanese carriers at about the same time Japanese scout planes spotted the American carriers. The Japanese Zuiho's flight deck was holed by the scout bombers, cancelling flight operations, but the other three enemy carriers launched strikes. The two air armadas tangled as each strove to reach the other's carriers. The Hornet was hit repeatedly by bombs and torpedoes; two Japanese pilots also crashed their planes on board. The damage to the ship was so extensive, the Hornet was abandoned and sunk. The Enterprise, the battleship South Dakota, the light cruiser San Juan (CL-54), and the destroyer Porter (DD-356) were sunk. On the Japanese side, no ships were sunk, but three carriers and two destroyers were damaged. One hundred Japanese planes were lost; 74 U.S. planes went down. Taken together, the results of the Battle of Santa Cruz were a standoff. The Japanese naval leaders might have continued their attacks, but instead, disheartened by the defeat of their ground forces on Guadalcanal, withdrew to attack another day.

The departure of the enemy naval force marked a period in which substantial reinforcements reached the island. The headquarters of the 2d Marines had finally found transport space to come up from Espiritu Santo and on 29 and 30 October, Colonel Arthur moved his regiment from Tulagi to Guadalcanal, exchanging his 1st and 2d Battalions for the well-blooded 3d, which took up the Tulagi duties. The 2d Marines' battalions at Tulagi had performed the very necessary task of scouting and securing all the small islands of the Florida group while they had camped, frustrated, watching the battles across Sealark Channel. The men now would no longer be spectators at the big show. On 2 November, planes from VMSB-132 and VMF-211 flew into the Cactus fields from New Caledonia. MAG-11 squadrons moved forward from New Caledonia to Espiritu Santo to be closer to the battle scene; the flight echelons now could operate forward to Guadalcanal and with relative ease. On the ground side, two batteries of 155mm guns, one Army and one Marine, landed on 2 November, providing Vandegrift with his first artillery units capable of matching the enemy's long-range 150mm guns. On the 4th and 5th, the 8th Marines (Colonel Richard H.J. Jeschke) arrived from American Samoa. The full-strength regiment, reinforced by the 75mm howitzers of the 1st Battalion, 10th Marines, added another 4,000 men to the defending forces. All the fresh troops reflected a renewed emphasis at all levels of command on making sure Guadalcanal would be held. The reinforcement-replacement pipeline was being filled. In the offing as part of the Guadalcanal defending force were the rest of the Americal Division, the remainder of the 2d Marine Division, and the Army's 25th Infantry Division, then in Hawaii. More planes of every type and from Allied as well as American sources were slated to reinforce and replace the battered and battle-weary Cactus veterans.

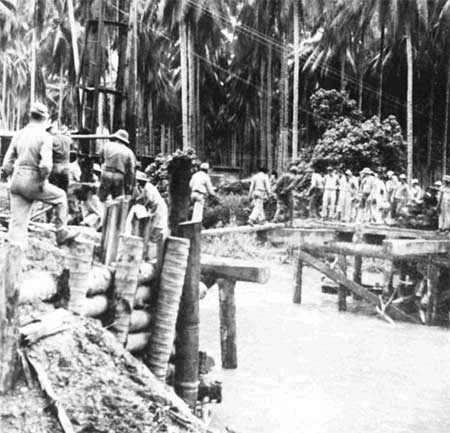

The impetus for the heightened pace of reinforcement had been provided by President Roosevelt. Cutting through the myriad demands for American forces worldwide, he had told each of the Joint Chiefs on 24 October that Guadalcanal must be reinforced, and without delay. On the island, the pace of operations did not slacken after the Maruyama offensive was beaten back. General Vandegrift wanted to clear the area immediately west of the Matanikau of all Japanese troops, forestalling, if he could, another buildup of attacking forces. Admiral Tanaka's Tokyo Express was still operating and despite punishing attacks by Cactus aircraft and new and deadly opponents, American motor torpedo boats, now based at Tulagi. On 1 November, the 5th Marines, backed up by the newly arrived 2d Marines, attacked across bridges engineers had laid over the Matanikau during the previous night. Inland, Colonel Whaling led his scout-snipers and the 3d Battalion, 7th Marines, in a screening movement to protect the flank of the main attack. Opposition was fierce in the shore area where the 1st Battalion, 5th, drove forward toward Point Cruz, but inland the 2d Battalion and Whaling's group encountered slight opposition. By nightfall, when the Marines dug in, it was clear that the only sizable enemy force was in the Point Cruz area. In the day's bitter fighting, Corporal Anthony Casamento, a badly wounded machine gun squad leader in Edson's 1st Battalion, had so distinguished himself that he was recommended for a Navy Cross; many years later, in August 1980, President Jimmy Carter approved the award of the Medal of Honor in its stead.

On the 2d, the attack continued with the reserve 3d Battalion moving into the fight and all three 5th Marines units moving to surround the enemy defenders. On 3 November, the Japanese pocket just west of the base at Point Cruz was eliminated; well over 300 enemy had been killed. Elsewhere, the attacking Marines had encountered spotty resistance and advanced slowly across difficult terrain to a point about 1,000 yards beyond the 5th Marines' action. There, just as the offensive's objectives seemed well in hand, the advance was halted. Again, the intelligence that a massive enemy reinforcement attempt was pending forced Vandegrift to pull back most of his men to safeguard the all-important airfield perimeter. This time, however, he left a regiment to outpost the ground that had been gained, Colonel Arthur's 2d Marines, reinforced by the Army's 1st Battalion, 164th Infantry. Emphasizing the need for caution in Vandegrift's mind was the fact that the Japanese were again discovered in strength east of the perimeter. On 3 November, Lieutenant Colonel Hanneken's 23d Battalion, 7th Marines, on a reconnaissance in force towards Kili Point, could see the Japanese ships clustered near Tetere, eight miles from the perimeter. His Marines encountered strong Japanese resistance from obviously fresh troops and he began to pull back. A regiment of the enemy's 38th Division had landed, as Hyakutake experimented with a Japanese Navy-promoted scheme of attacking the perimeter from both flanks.

As Hanneken's battalion executed a fighting withdrawal along the beach, it began to receive fire from the jungle inland, too. A rescue force was soon put together under General Rupertus: two tank companies, the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, and the 2d and 3d Battalions of the 164th. The Japanese troops, members of the 38th Division regiment and remnants of Kawaguchi's brigade, fought doggedly to hold their ground as the Marines drove forward along the coast and the soldiers attempted to outflank the enemy in the jungle. The running battle continued for days, supported by Cactus air, naval gunfire, and the newly landed 155mm guns.

The enemy commander received new orders as he was struggling to hold off the Americans. He was to break off the action, move inland, and march to rejoin the main Japanese forces west of the perimeter, a tall order to fulfill. The two-pronged attack scheme had been abandoned. The Japanese managed the first part; on the 11th the enemy force found a gap in the 164th's line and broke through along a meandering jungle stream. Behind they left 450 dead over the course of a seven-day battle; the Marines and soldiers had lost 40 dead and 120 wounded. Essentially, the Japanese who broke out of the encircling Americans escaped from the frying pan only to fall into the fire. Admiral Turner finally had been ably to effect one of his several schemes for alternative landings and beachheads, all of which General Vandegrift vehemently opposed. At Aola Bay, 40 miles east of the main perimeter, the Navy put an airfield construction and defense force ashore on 4 November. Then, while the Japanese were still battling the Marines near Tetere, Vandegrift was able to persuade Turner to detach part of this landing force, the 2d Raider Battalion, to sweep west, to discover and destroy any enemy forces it encountered. Lieutenant Colonel Evans F. Carlson's raider battalion already had seen action before it reached Guadalcanal. Two companies had reinforced the defenders of Midway Island when the Japanese attacked there in June. The rest of the battalion had landed from submarines on Makin Island in the Gilberts on 17-18 August, destroying the garrison there. For his part in the fighting on Makin, Sergeant Clyde Thomason had been awarded a Medal of Honor posthumously, the first Marine enlisted man to receive his country's highest award in World War II. In its march from Aola Bay, the 2d Raider Battalion encountered the Japanese who were attempting to retreat to the west. On 12 November, the raiders beat off attacks by two enemy companies and they relentlessly pursued the Japanese, fighting a series of small actions over the next five days before the contacted the main Japanese body. From 17 November to 4 December, when the raiders finally came down out of the jungled ridges into the perimeter, Carlson's men harried the retreating enemy. They killed nearly 500 Japanese. Their own losses were 16 killed and 18 wounded. The Aola Bay venture, which had provided the 2d Raider Battalion a starting point for its month-long jungle campaign, proved a bust. The site chosen for a new airfield was unsuitable, too wet and unstable, and the whole force moved to Koli Point in early December, where another airfield eventually was constructed. The buildup on Guadalcanal continued, by both sides. On 11 November, guarded by a cruiser-destroyer covering force, a convoy ran in carrying the 182d Infantry, another regiment of the Americal Division. The ships were pounded by enemy bombers and three transports were hit, but the men landed. General Vandegrift needed the new men badly. His veterans were truly ready for replacement; more than a thousand new cases of malaria and related diseases were reported each week. The Japanese who had been on the island any length of time were no better off; they were, in fact, in worse shape. Medical supplies and rations were in short supply. The whole thrust of the Japanese reinforcement effort continued to be to get troops and combat equipment ashore. The idea prevailed in Tokyo, despite all evidence to the contrary, that one overwhelming coordinated assault would crush the American resistance. The enemy drive to take Port Moresby on New Guinea was put on hold to concentrate all efforts on driving the Americans off of Guadalcanal.

On 12 November, a multifaceted Japanese naval force converged on Guadalcanal to cover the landing of the main body of the 38th Division. Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan's cruisers and destroyers, the close-in protection for the 182d's transports, moved to stop the enemy. Coastwatcher and scout plane sightings and radio traffic intercepts had identified two battleships, two carriers, four cruisers, and a host of destroyers all headed toward Guadalcanal. A bombardment group led by the battleships Hiei and Kirishima, with the light cruiser Nagura, and 15 destroyers spearheaded the attack. Shortly after midnight, near Savo Island, Callaghan's cruisers picked up the Japanese on radar and continued to close. The battle was joined at such short range that each side fired at times on their own ships. Callaghan's flagship, the San Francisco, was hit 15 times, Callaghan was killed, and the ship had to limp away. The cruiser Atlanta (CL-104) was also hit and set afire. Rear Admiral Norman Scott, who was on board, was killed. Despite the hammering by Japanese fire, the Americans held and continued fighting. The battleship Hiei, hit by more than 80 shells, retired and with it went the rest of the bombardment force. Three destroyers were sunk and four others damaged. The Americans had accomplished their purpose; they had forced the Japanese to turn back. The cost was high. Two antiaircraft cruisers, the Atlanta and the Juneau (CL-52), were sunk; four destroyers, the Barton (DD-599), Cushing (DD-376), Monssen (DD-436), and Laffey (DD-459), also went to the bottom. In addition to the San Francisco, the heavy cruiser Portland and the destroyers Sterret (DD-407), and Aaron Ward (DD-483) were damaged. One one destroyer of the 13 American ships engaged, the Fletcher (DD-445), was unscathed when the survivors retired to the New Hebrides. With daylight came the Cactus bombers and fighters; they found the crippled Hiei and pounded it mercilessly. On the 14th the Japanese were forced to scuttle it. Admiral Halsey ordered his only surviving carrier, the Enterprise, out of the Guadalcanal area to get it out of reach of Japanese aircraft and sent his battleships Washington (BB-56) and South Dakota with four escorting destroyers north to meet the Japanese. Some of the Enterprise's planes flew in to Henderson Field to help even the odds.

On 14 November Cactus and Enterprise flyers found a Japanese cruiser-destroyer force that had pounded the island on the night of 13 November. They damaged four cruisers and a destroyer. After refueling and rearming they went after the approaching Japanese troop convoy. They hit several transports in one attack and sank one when they came back again. Army B-17s up from Espiritu Santo scored one hit and several near misses, bombing from 17,000 feet. Moving in a continuous pattern of attack, return, refuel, rearm, and attack again, the planes from Guadalcanal hit nine transports, sinking seven. Many of the 5,000 troops on the stricken ships were rescued by Tanaka's destroyers, which were firing furiously and laying smoke screens in an attempt to protect the transports. The admiral later recalled that day as indelible in his mind, with memories of "bombs wobbling down from high-flying B-17s; of carrier bombers roaring towards targets as though to plunge full into the water, releasing bombs and pulling out barely in time, each miss sending up towering clouds of mist and spray, every hit raising clouds of smoke and fire." Despite the intensive aerial attack, Tanaka continued on to Guadalcanal with four destroyers and four transports. Japanese intelligence had picked up the approaching American battleship force and warned Tanaka of its advent. In turn, the enemy admirals sent their own battleship-cruiser force to intercept. The Americans, led by Rear Admiral Willis A. Lee in the Washington, reached Sealark Channel about 2100 on the 14th. An hour later, a Japanese cruiser was picked up north of Savo. Battleship fire soon turned it away. The Japanese now learned that their opponents would not be the cruisers they expected. The resulting clash, fought in the glare of gunfire and Japanese searchlights, was perhaps the most significant fought at sea for Guadalcanal. When the melee was over, the American battleships' 16-inch guns had more than matched the Japanese. Both the South Dakota and the Washington were damaged badly enough to force their retirement, but the Kirishima was punished to its abandonment and death. One Japanese and three American destroyers, the Benham (DD-796), the Walke (DD-416), and the Preston (DD-379), were sunk. When the Japanese attack force retired, Admiral Tanaka ran his four transports onto the beach, knowing they would be sitting targets at daylight. Most of the men on board, however, did manage to get ashore before the inevitable pounding by American planes, warships, and artillery.

Ten thousand troops of the 38th Division had landed, but the Japanese were in no shape to ever again attempt a massive reinforcement. The horrific losses in the frequent naval clashes, which seemed at times to favor the Japanese, did not really represent a standoff. Every American ship lost or damaged could and would be replaced; every Japanese ship lost meant a steadily diminishing fleet. In the air, the losses on both sides were daunting, but the enemy naval air arm would never recover from its losses of experienced carrier pilots. Two years later, the Battle of the Philippine Sea between American and Japanese carriers would aptly be called the "Marianas Turkey Shoot" because of the ineptitude of the Japanese trainee pilots.

The enemy troops who had been fortunate enough to reach land were not immediately ready to assault the American positions. The 38th Division and the remnants of the various Japanese units that had previously tried to penetrate the Marine lines needed to be shaped into a coherent attack force before General Hyakutake could again attempt to take Henderson Field. General Vandegrift now had enough fresh units to begin to replace his veteran troops along the front lines. The decision to replace the 1st Marine Division with the Army's 25th Infantry Division had been made. Admiral Turner had told Vandegrift to leave all of his heavy equipment on the island when he did pull out "in hopes of getting your units re-equipped when you come out." He also told the Marine general that the Army would command the final phases of the Guadalcanal operation since it would provide the majority of the combat forces once the 1st Division departed. Major General Alexander M. Patch, commander of the Americal Division. would relieve Vandegrift as senior American officer ashore. His air support would continue to be Marine-dominated as General Geiger, now located on Espiritu Santo with 1st Wing headquarters, fed his squadrons forward to maintain the offensive. And the air command on Guadalcanal itself would continue to be a mixed bag of Army, Navy, Marine, and Allied squadrons. The sick list of the 1st Marine Division in November included more than 3,200 men with malaria. The men of the 1st still manning the frontline foxholes and the rear areas—if anyplace within Guadalcanal's perimeter could properly be called a rear area—were plain worn out. They had done their part and they knew it. On 29 November, General Vandegrift was handed a message from the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The crux of it read: "1st MarDiv is to be relived without delay ... and will proceed to Australia for rehabilitation and employment." The word soon spread that the 1st was leaving and where it was going. Australia was not yet the cherished place it would become in the division's future, but any place was preferable to Guadalcanal.

|