|

Kenai Fjords

A Stern and Rock-Bound Coast: Historic Resource Study |

|

Chapter 7:

THE LURE OF GOLD

Most of the Kenai Peninsula exhibits little evidence of mineralization, and mines on the peninsula, while numerous, have contributed only a minor portion of the state's mineral output. Few economically viable mines have been established on the eastern or western part of the peninsula. Extending in a generally north-south direction across the peninsula's central portion, however, is a belt of country rock consisting of alternating beds of slate and graywacke. Igneous dikes that are currently referred to as greenstones have locally intruded that rock mass. The dikes occupy fractures of irregular form and moderate extent; free gold is the primary mineral with economic importance, though sulfides are by no means uncommon. (The dikes also contain minor quantities of silver, copper, lead, and zinc.) Those dikes are found in an irregular belt that extended from the Hope and Sunrise areas south to Kenai Lake, while others are found along the North and West arms of Nuka Bay. Other mineralized areas on the peninsula are found on both the eastern and western slopes fronting on Resurrection Bay, along the Resurrection River, and additional sites scattered across the peninsula. [1]

Early Kenai Peninsula

Exploration

|

| Map 7-1. Historic Sites-Gold Mining. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

As noted in Chapter 3, the first known mine on Kenai Peninsula was started at the behest of Peter Doroshin, a Russian mining engineer who visited the American colonies in search of potential mineral resources. In addition to the Port Graham coal deposits (which were mined during the 1850s and 1860s), Doroshin also found minor gold deposits along both the Kenai and Russian rivers. Little additional prospecting took place until the early 1880s, when Joseph M. Cooper sought gold near present-day Cooper Landing. In 1889, coal was extracted near present-day Homer, and the following year gold was obtained near Anchor Point. Both endeavors were commercially unsuccessful. [2]

More promising gold deposits were found along the peninsula's northern shore. A man named King discovered gold near present-day Hope about 1888, and shortly afterward, Charles Miller staked a gold claim on Resurrection Creek. The area remained fairly quiet, however, until 1893 when the creek witnessed new discoveries. Increasing numbers of miners arrived in 1894, and a remarkable find in July 1895 by John Renner and Robert Michaelson brought a major rush–perhaps 3,000 men and women–to the shores of Turnagain Arm the following year. Scores if not hundreds of claims were made in the Sixmile and Canyon creek drainages as well as within the Resurrection Creek drainage system. The towns of Hope and Sunrise boomed for the remainder of the decade, both diminishing in importance in later years. By 1911, Sunrise was practically deserted and by the 1930s most of the buildings had vanished. [3] Hope lost most of its population, too, but unlike Sunrise, Hope never "ghosted."

By the early twentieth century, prospectors had begun locating minerals in the southern peninsula as well. This may have been a result of the Hope-Sunrise excitement; the commencement of a large copper mine on nearby Latouche Island may have played a role; and the establishment of Seward in 1903 doubtless encouraged local mineral prospecting. Regardless of the reason, two claims had been staked in the Seward area by October 1904; both were located in Sunny Bay (present-day Humpy Cove) on the east side of Resurrection Bay. During the next several years, copper was found at a number of Resurrection Peninsula sites, and a minor (if well-publicized) copper rush ensued. Although the early reports on the copper claims appeared promising, no development occurred to compare with the copper mines of Latouche Island, and copper miners turned their interest elsewhere. Gold was also found in the area, most notably the Gateway Group along Tonsina Creek, but little if any production took place. By 1910, all development work for both copper and gold had ceased. [4]

Prospecting also took place during this period at the Kenai Peninsula's southwestern tip. A 1909 report noted that gold and other prospects had been located (probably since 1905) both at the west end of Windy Bay and near Port Dick. Ore quantities, however, were insufficient to justify production. [5]

Of particular interest to both prospectors and government geologists were the chromite (chromic iron) deposits west of Port Dick. Two deposits were known: one at Chrome Bay, near the mouth of Port Chatham, the other on the north side of Red Mountain, southeast of Seldovia. These deposits were known prior to 1910, but the Port Chatham deposit became of commercial interest only in 1917, when the price of ore rose because of wartime needs. [6] Whitney and Lass produced about a thousand tons of ore both that year and in 1918. By 1919, a "considerable plant investment" had been made, resulting in the production of "chrome of good quality." The company, however, mined no ore that year due to a return to prewar price levels. The plant soon closed and did not reopen. [7] At Red Mountain, commercial development did not take place until World War II. The mine operated from 1942 to 1944, and again from 1954 to 1957. [8]

Nuka Bay Gold Mining: A

Chronology

Government geologist U. S. Grant noted, after traveling through the area in 1909, that the outer coast was "entirely uninhabited." Prospectors, however, had previously visited the area. As noted in Chapter 5, George Stinson may have been one of the present-day park's first prospectors, in 1896. A group of miners were heading up the coast to the Hope-Sunrise diggings that year when a storm forced them to retreat to Nuka Bay. Stinson was intrigued by "rich-looking float" he found on the beach. The find, however, did not deter him from continuing on to Turnagain Arm, and the incident was soon forgotten. [9] Several years later, other prospectors (as noted above) located claims at Windy Bay and Port Dick and doubtless searched in many other locations.

Grant's report noted that prospecting parties had made gold claims in two general areas within the present park. One area was Two Arm Bay. It stated that on the mountain at the head of Taroka Arm, John Kusturin and Gus Johansen had staked nine claims on three quartz veins. [10] Development work had been limited to "some small stripping" of the veins. Grant also wrote that the east side of nearby Paguna Arm had "a few small quartz veins," an assay from which showed no gold. Near the head of Paguna Arm were seen "a few granite dikes." An assay from that deposit showed $1.80 per ton in gold, an amount that was insufficient to justify development work. This activity appears to have taken place between 1907 and 1909. The claims soon lapsed, and the area has remained idle ever since. [11]

The other area that had incited the interest of early prospectors was Nuka Bay. During the first decade of the twentieth century, the bay's East Arm (McCarty Fjord) was relatively short–McCarty Glacier extended some fifteen miles farther south than it does today–and the glacier's face reached from the southern end of James Lagoon to the mouth of McCarty Lagoon. A four-man prospecting party–Daniel Morris, James Sheridan, George W. Kuppler, and John H. Lee–located three deposits in 1909, two on East Arm and a third on North Arm. [12] One of the East Arm deposits was on the flat at the west side of the McCarty Glacier face; a "number of pieces" of float quartz were found, but no vein was located. The party also found a broken quartz vein "near the south point of the first ridge" west of McCarty Glacier. The vein, which was approximately 300 yards from the ice in July 1909, was opened for only two or three feet. On Nuka Bay's North Arm, they discovered a third deposit, located near the center of the arm's west side. The party did not engage in development work. Since that time, the East Arm sites have probably lain fallow, but the North Arm deposit was later relocated and became part of the Rosness and Larson prospect. [13]

U. S. Grant, the geologist who visited the area in 1909, took samples of several of the area's quartz-arsenopyrite veins. He later assayed the samples but found that "the results of these assays ... is not encouraging." His report, which was published in preliminary form in 1910 and in final form in 1915, may have put a damper on area prospecting, inasmuch as no known deposits were discovered along the park's coastline between 1909 and 1917. [14]

When gold was next discovered in the area is open to some dispute. A government report written in 1918 noted that "a quartz lode carrying free gold discovered on Nuka Bay in 1917 has attracted some attention, and it is reported that this lode was being developed in 1918." But another such report, written years later, said that Nuka Bay gold had been discovered in 1918 by Frank Case and Otis Harrington. The gold discovery, regardless of when it happened, took place at the Alaska Hills deposit, two miles up the Nuka River from Beauty Bay. [15]

Additional claim filing apparently followed these early discoveries, and by the spring of 1920, a bullish article in The Pathfinder stated that

Nuku Bay [sic], about eighty miles distant from Seward, is a quartz mining district. Although only discovered a few years ago, three large plants are operating continuously, and the average values are very high. This district is attracting considerable attention. [16]

The Alaska Hills deposit was probably one of the three "plants" in operation that spring. The identity of the remaining mines, however, is unknown, and it is doubtful if more than rudimentary excavations took place at those sites during this period.

Area mineral activity began to revive in 1922 when Charles Emsweiler, a Seward-based game guide and policeman, located a vein of free milling gold at the head of Beauty Bay. Emsweiler, working alone, mined one thousand pounds of ore from the outcrop of his find and packed it on his back to tide water. He took it to Seward and then transshipped it to the smelter at Tacoma. The shipment netted $80. The ore doubtless increased interest among some area miners, but the area received little additional publicity. [17]

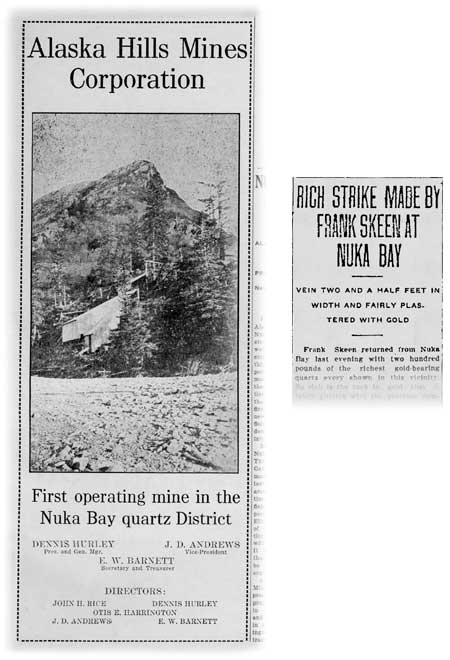

Frank P. Skeen, who had been prospecting in the area for more than 15 years, [18] then relocated the veins–350 feet southeast of the Emsweiler deposit–that Case and Harrington had discovered five years earlier. Skeen's "discovery," which took place in late June 1923, made front-page headlines in the July 2 issue of the Seward Gateway:

RICH STRIKE MADE BY FRANK SKEEN AT NUKA BAY

Vein Two and a Half Feet in Width

and Fairly Plastered with GoldFrank Skeen returned from Nuka Bay last evening with two hundred pounds of the richest gold-bearing quartz ever shown in this vicinity. So rich is the rock in gold that it fairly glitters with the precious mineral, and old timers who have seen the samples state they are better than have been shown in Alaska for many a day.

The vein, which is two and a half feet wide at the surface, was found by Mr. Skeen while burning off the grass around a property held by him at Nuka Bay. A piece about as large as one's fist was discovered sticking out of the ground, and upon examination the larger vein was found. Mr. Skeen stripped the vein for fifty feet and it showed the same high values at all points with no diminution in width. The vein is in block slate formation similar to the deep mines of California, and has every sign of permanency.

The new strike is about a mile and a half from salt water, on the Nuka River, and at about 500 feet in elevation. A wagon could be driven from the saltchuck to the mine. [19]

|

| Frank Skeen's June 1923 gold discovery led to the Alaska Hills Mine, which was the first commercially productive mine in the Nuka Bay district. The mill, shown in the photograph, was completed in November 1924; it operated until 1928. Seward Gateway, December 5, 1925, 9. |

Skeen soon returned to Nuka Bay to develop his property, and before long he brought back to Seward further proof of the claim's wealth. In late August, he exhibited a half ounce of gold that had been washed out from ten ounces of rock, and he also announced, based on recent assay results, that he had specimens showing values of more than $3000 per ton. These yields, according to newspaper reports, "caused considerable excitement among the old timers of this vicinity, and a number of prospectors and their outfits have taken gas boats for the scene of the strike." [20] A minor rush ensued, with Anchorage as well as Seward residents taking part; by early September, there were "some 65 miners and prospectors at the scene of the strike." One visitor to the claim announced that the strike "was all that it was reported to be, and more. Mr. Skeen has a wonderfully rich property there." [21]

The Pathfinder of Alaska gave an enthusiastic, detailed account of Skeen's discovery:

A sensationally rich gold quartz strike has been made in the Nuka Bay section, a short distance from Anchorage. Samples taken from the lead, which is exposed on the surface for a hundred or more feet, are said to go into the hundreds and even thousands of dollars. The silver content goes about $50 per ton, according to the assays.

The find was first made in June by Frank P. Skeen, an experienced hard-rock man of 25 years' residence in the north. The discovery was made as a result of finding a piece of quartz that was literally alive with gold, according to Skeen. Using his prospector's pick he began to dig around in the grass covered ground near the spot where the float was found and luckily encountered the vein. Skeen uncovered it for about 20 feet, enough to show that he had found a wonderful prospect. The vein at this point was about 20 inches in width and is what is termed a true fissure vein, crosscutting the formation. There is a sort of gouge in both walls, Skeen says, from which he picked out pieces that appeared to be plated with gold. Gold, he says, can be seen in much of the quartz, although there is a heavier concentration along the walls.

Subsequent development has revealed an ore body estimated to contain approximately $200,000 in what can be seen of it. The formation of the district is a black slate, occurring in blocks, and acidic and porphry [porphyry] dikes running through the country which are said to give encouraging prospects. [22]

The prospectors who invaded the area on the heels of Skeen's strike doubtless investigated the area surrounding his claims. Finding little, they fanned out across Nuka Bay and beyond, and scores registered claims. (Most claims were located near either the North Arm or West Arm of Nuka Bay, but some were made as far south as Tonsina Bay or as far north as Aialik Bay.) [23] By the summer of 1924, development work had taken place on at least six prospects, and work began on perhaps a dozen others as the decade wore on. [24]

Prospecting continued in the Nuka Bay area throughout the 1920s, but well before the end of the decade it became increasingly obvious that paying properties would be few and far between. As government geologist J. G. Shepard noted in a 1925 report, "it is not likely that the District will ever be an important producer, although small tonnages of commercial ore will probably be worked from time to time." [25] Factors such as remoteness, poor transportation, snowslides, and late-spring snow accumulations doubtlessly retarded progress. Another retarding factor, common to small-scale operations, was poor management. As geologist Robert Heath noted in 1932 after a visit to the area,

The greatest obstacle seems to be lack of men who understand the business and technique of mining. There have been many expensive mistakes made in the past by the pioneer operators that could be avoided by a new company just entering the field.... Practically all of the attempts at mining have been promoted and conducted by men who were trained in other kinds of work.

Primarily, however, the area's lack of development was due to a lack of economically extractable gold. [26]

During the 1920s, relatively few properties had sufficient ore to justify production. Two mines produced gold: the first, beginning in 1924, was the Alaska Hills Mine, which had been "rediscovered" by Frank Skeen just the year before. Four years later, the Sonny Fox Mine, at the head of Surprise Bay, was the second Nuka Bay mine to commence production. That so few properties were able to operate during the 1920s was, in large part, due to conditions that prevailed throughout the Territory; gold production in general, and lode gold production in particular, dipped to its lowest level in more than a decade. [27]

The Great Depression years of the 1930s were poor for the nation's business, but judging by production figures, they were relatively favorable for the Alaska gold mining industry. Gold production rose gradually during the early 1930s. Then, in January 1934, gold mining received a further boost when the U.S. government (which was the only legal gold buyer) raised the price of gold from $20.67 to $35 per troy ounce. In the Nuka Bay area, production rose and new properties began milling gold. The Rosness and Larson mine, on the west side of North Arm, began operating in 1931; the Goyne Prospect, on Surprise Bay, sent out its first ore the same year; and in 1934, the year gold prices rose, the Nukalaska Mine commenced production. [28]

A government report published in 1931 was bullish about the district. It noted that the Sonny Fox mine, in operation since 1926, was the area's top producer. In addition,

there are more than a dozen other properties in the district on which development work was in progress, and of these at least three shipped some ore or concentrates to smelters in the States for treatment. The properties at which work was in progress are widely distributed through the district, indicating that the mineralization is not localized at a few points. The success that already attended the operations of the Sonny Fox mine and the samples that have been assayed from many of the other properties give assurance that the mineralization in many places has produced ores that, if skillfully mined and milled, are of commercial grade. [29]

By 1933, however, optimism about the district had begun to dim. A U.S. Geological Survey report noted that "on the whole, small-scale prospecting does not appear to have been so active during 1933 as in the preceding year," and prospecting continued to decrease in 1934. Even the local chamber of commerce, which had been publicizing its potential just two years earlier, chose not to recommend the area as a potential mining area in a December 1934 letter. [30]

During the late 1930s, interest in the Nuka Bay mines continued to subside. The Geological Survey's 1937 report on Alaska mining noted that "mining was carried on at a somewhat slower rate than formerly." There were three producing properties–Nukalaska, Sonny Fox, and Alaska Hills–but "at none of the other mines were any notable new developments in progress, and no new prospecting enterprises are reported to have been started during the year." The following year's report stated that

perhaps half a dozen properties on which some work was done during the year, but the wave of interest that brought this camp to notice a few years ago seems to have subsided, so that many of the early comers have drifted away and mining has dropped to a low stage.

The 1939 report noted that work continued on six properties, "but at only three of them [the same three noted above] was the work much more than casual prospecting." [31] By the end of 1941, production had ceased throughout the district; the area remained idle until after World War II.

Between 1924 and 1941, a total of five mines produced and shipped gold ore. Two of the five (the Sonny Fox Mining Company and the Alaska Hills Mine) operated for ten or more years; one mine (the Nukalaska Mine) operated for five to nine years, and the final two (the Rosness and Larson Mine and the Goyne Prospect) produced gold for fewer than five years. Most of the mines were small in scale, with a crew numbering six or fewer, and in almost all cases the operations were seasonal, usually lasting from late April or early May until September or October. [32]

Little if any gold production data was ever published from these mines. [33] In the 1960s, however, geologist Donald Richter estimated production quantities based on mill capacities, gold values, yields per ton and scattered unofficial reports. On that basis, he estimated that the district produced perhaps $166,000 in gold between 1924 and 1940. The largest producer, the Sonny Fox Mine, yielded some $70,000 in gold. Production from the Alaska Hills Mine was $45,000; from the Nukalaska Mine, $35,000; and from the Rosness and Larson Mine, $15,000. (All figures are approximate.) The Goyne Prospect yielded an insignificant amount of gold–less than $1,000, according to Richter's estimate. [34]

By any measure, the yields from the Nuka Bay district were minor. The district yielded an average annual total of $10,000 in gold during the 1924-1940 period. [35] During those 17 years, however, the annual total of lode gold production in Alaska ranged from $2.7 million to $8.3 million, and the annual total of Alaska gold production (from both lode and placer mines) ranged from $5.9 million to $26.2 million. Using the most conservative measurement, therefore, the Nuka Bay mines do not appear to have ever contributed more than one percent of Alaska's lode production, and they consistently produced less than 0.3% of Alaska's total gold production. [36] Based on those yields, it is not surprising that the Nuka Bay mines (and other Kenai Peninsula gold mines) were consistently described in the "other districts" section of the U.S. Geological Survey's annual reports.

Mining on the Kenai Peninsula, as elsewhere in Alaska, revived slowly during the postwar years. Economic prosperity brought more jobs and rising wages, luring miners to the cities. The prices of mining equipment, moreover, increased along with other products. The price of gold, however, held steady at $35 per ounce. [37]

Because of those obstacles, and because the most promising veins had already been tapped, the level of Nuka Bay mining activity was far less than it had been before World War II. Sometime during the postwar period, the Golden Horn group unsuccessfully attempted to reopen the Goyne prospect on Surprise Bay. In July 1951, Wyman Anderson and B. C. Rick expressed an interest in the old Sonny Fox mine; they transferred the property to the Alaska Exploration and Development Corporation, which held the property for the next several years. Sometime in the 1950s a group from Hawaii, locally known as the Honolulu Group, unsuccessfully attempted to reopen the Nukalaska Mine but the venture was apparently short-lived. In 1959 and 1960, several Seward residents conducted development work at the Little Creek (Glass and Heifner) prospect, near the head of Beauty Bay. None of these attempts resulted in commercial production, however, and after a 1967 visit, geologist Donald Richter noted "today the area has been virtually forgotten." [38]

|

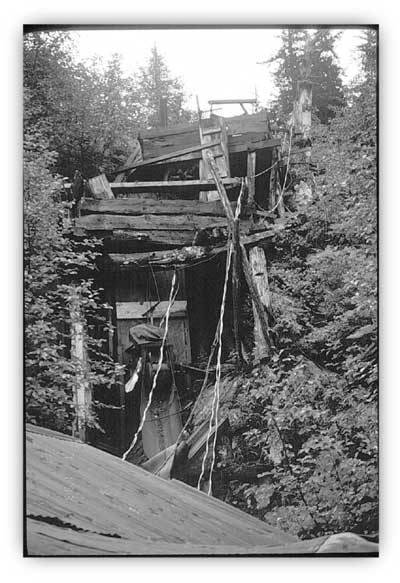

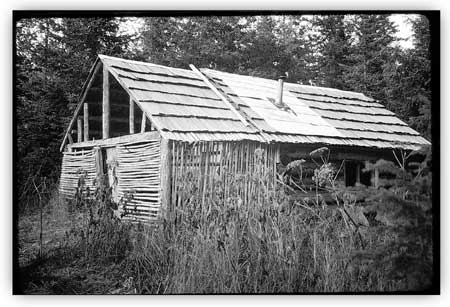

| Remains of tunnels, mining equipment, camp buildings and roads are scattered throughout the West Arm and North Arm of Nuka Bay. This 1970s-era photo may have been taken at the Goyne/Golden Horn prospect. Don Follows photo, NPS/Alaska Area Office print file, NARA Anchorage. |

The dramatic rise in the price of gold, beginning in 1968, favorably affected gold mining operations throughout the United States. Perhaps as a result, at least one recently active Nuka Bay mine has produced commercial quantities of gold, and small-scale activity has taken place elsewhere. In 1965, a group from Jamestown, Ohio, acquired the former Little Creek prospect; soon afterward, they constructed a small mill and mined "a limited amount" of ore. The pair operated on an intermittent, small-scale basis until the early 1980s; since then, others have extracted ore from time to time. At the Sonny Fox mine site, the ground was re-staked in 1968 and it remained an active claim site for more than twenty years thereafter. Other active development work in recent years has taken place at the old Goyne-Golden Horn prospect. During the early 1970s, there was also a purported barium deposit on the east side of Harris Bay. The four claims that encompassed that deposit, however, lapsed before the end of the decade. [39]

Nuka Bay Mining Sites: Beauty

Bay

Alaska Hills Mines Corporation

The first gold known to be discovered in the area surrounding Beauty Bay took place at the Alaska Hills deposit, two miles up the Nuka River from Beauty Bay. When the discovery took place is open to debate. As noted in the section above, a government report written in 1918 stated that "a quartz lode carrying free gold discovered on Nuka Bay in 1917 has attracted some attention, and it is reported that this lode was being developed in 1918." But a similar report, written during the mid-1930s, said that the gold discovery, by Frank Case and Otis Harrington, took place in 1918. [40] Additional claim filing may have followed that discovery, but no development work immediately ensued, and by the early 1920s, Case and Harrington had either relinquished or sold their claim.

Mineral activity in the area remained quiet until the early 1920s. As noted above, one source notes that gold was discovered nearby, in 1922, by Charles Emsweiler, a Seward-based game guide and policeman. Emsweiler apparently extracted a half ton of ore and sent it to Tacoma for smelting. [41] Then, a year later, the Case-Harrington claim was rediscovered by Frank P. Skeen, a prospector who had been living and working on the peninsula since 1907 if not before. Skeen had apparently acquired Case and Harrington's claim and, as noted above, was "burning off the grass" around his property in late June 1923 when he located a quartz vein that was "two and a half feet in width and fairly plastered with gold." Skeen stripped the vein for fifty feet and found it to be consistently rich; he then extracted two hundred pounds of ore and took it back to Seward for assaying. [42]

Table 7-1. Elements Comprising the Nuka Bay Mining District

| Mine Area and Name | Years of Commerical Operation | Identified Historical Register (pre-1948) Elements | National Register Eligibility |

Beauty Bay: | |||

| Alaska Hills Mining Corp. | 1925-28, 1931, 1937-41 | mill, adits (4), improved trail, tramway, log bunkhouses (2) | not evaluated |

| Nuka Bay Mining Company (Harrington Prospect) |

[none] | adits (2), open cuts, small mill, trail, upper camp, lower camp [cabins?] | not evaluated |

| Nukalaska Mining Company | 1934-38 (+1939-41?) |

road, tramway (2), mill (old and new), machine shop; camp buildings (4) and tents (2); bunkhouse/ore bin/tram terminal at adit #1; compressor shed at adit #2, tents (2); cabin and storehouse at beach | yes, 1991; SHPO concurs |

| Glass and Heifner Mine (Earl Mount/Little Creek Prospects) |

1965-85? | Open cuts, adit, camp, shaft, raise (all probably obliterated by 1965-85 work) | not evaluated |

| Miscellaneous Sites | [none] | adit, cabins (2) | not evaluated |

North Arm: | |||

| Rosness and Larson Property | 1931-33 | surface trenching, bulkhead, hoist, adits (3), winze, mill, log cabin, tents (2) | not evaluated |

| Kasanek-Smith Prospect | [none] | adit, surface trenches; cabin at nearby cove | not evaluated |

| Robert Hatcher Prospects | [none] | open cut, adits (4), cabin | not evaluated |

| Charles Frank Prospect | [none] | adit, cabin | not evaluated |

Surprise and Quartz Bays: | |||

| Sonny Fox Mine (Babcock and Downey Mine) |

1928-40 | trail, mill (old and new, surface tram, aerial tram, dock, adits (6), open cuts, camp buildings (5) | yes, 1991; SHPO concurs |

| Skinner Prospect #1 | [none] | adit | not evaluated |

| Johnston and Deegan Property | [none] | surface trenches, cabins (2), trails | not evaluated |

| Goyne Prospect (Golden Horn Property] |

1931-34 | tunnels (2), shallow pits, cabin, trail; bunkhouse? | not evaluated |

West Arm and Yalik Bay: | |||

| Lang-Skinner Prospect | [none] | open cuts, tunnels (4), frame house, log cabin; another cabin at "Lang's Beach" | unable to locate |

| Blair-Sather Prospect | [none] | adits (2), frame house | not evaluated |

Skeen soon returned to Nuka Bay to develop his claim. In late August, he exhibited a half ounce of gold that had been washed out from ten ounces of rock, and he also announced that he had specimens showing values of more than $3000 per ton. These yields, as noted above, "caused considerable excitement among the old timers of this vicinity" and caused a minor rush to the area; "some 65 miners and prospectors" had flocked to the area by early September. One visitor to the claim announced that the strike "was all that it was reported to be, and more. Mr. Skeen has a wonderfully rich property there." [43] Skeen called his claim the Paystreak.

Whether Skeen was the sole claimant at the time of his discovery is unknown, but by late August he had acquired several partners, including Earl W. Barnett and J. D. Andrews. [44]

During the winter of 1923-24, Skeen and his partners organized the Alaska Hills Mines Corporation. By the following summer, people working for the company had begun to dig two tunnels: an upper tunnel, at 570 feet above sea level and located on the vein, and a lower tunnel, 495 feet above sea level with drifting on the vein. Also under construction that summer was a mill, located at 40 feet above sea level and adjacent to left bank of Nuka River. The mill building contained a small Blake jaw crusher; a Worthington overflow-type, 5' x 5' ball mill; a drag classifier; amalgam plates; and a concentrating table. Its capacity was 40 tons per 24 hours. A 1,605-foot jigback aerial tramway, completed that year, connected the lower tunnel entrance with the mill, and "substantial camp buildings" (which probably consisted of two log bunkhouses) were also constructed. A two-mile trail connected the mill and adjacent camp with Beauty Bay, but it was so narrow that all the supplies for the mine had to be brought up the Nuka River on a barge. The mill was finally completed in November; a test run of ore was then processed, apparently with favorable results. [45]

In 1925, both the Paystreak Mine and the mill were active from May until November. By year's end, a tunnel (probably the upper tunnel) had been dug 200 feet into the hill and was following a vein 2 feet wide. The mill that year produced, in the opinion of government geologists, "a substantial production of lode gold;" the local newspaper reported that "about $12,000 in bullion" was produced. [46]

Based on that activity, the Alaska Road Commission agreed to improve the trail to the mine. The trail was "cleared, grubbed and graded 1_ miles for an average width of 7 feet." The grading included the blasting away of 1,507 cubic yards of solid rock, much of it along a narrow ledge; in addition, 200 linear feet of corduroy was laid and five timber culverts were constructed. By summer's end, the trail, which cost some $4,300, was "suitable for pack horses or double enders." The local newspaper editor judged the new trail to be "splendid." [47]

The Corporation held a stockholders' meeting in Seward in October and declared its first dividend. The directors had high hopes; they envisioned a post office and "a port for ocean-going steamers." Skeen was no longer part of the company; the primary participants at this time were J. D. Andrews and E. W. Barnett (who had been Frank Skeen's partners in 1923), who now served as the corporation's vice-president and secretary-treasurer, respectively. Other members of the board of directors included Dennis Hurley (president and general manager), Otis E. Harrington and John H. Rice. Miners included Jack Coffey and Jim Foster. [48]

The operation, however, was not without its problems. One major difficulty was an improperly designed mill. Noted one observer, "a great deal of gold has been lost in the tailings [because of the] failure of the concentrating tables to recover all of the sulphides in the ore." A properly designed flotation plant was recommended. Another visitor, moreover, criticized the extraction operation. Geologist J. G. Shepard noted that "the mine was poorly worked, no attention [having] been given to either chutes or manways." [49] In a late 1925 newspaper article, the company admitted that the mill had "been giving the company more or less difficulty during the first year's operations." They confidently stated, however, that it was "now doing much better and little future trouble is anticipated," and went on to describe that a cyanide plant, which had been recently installed, had "started up immediately and from last reports the recovery has been extremely gratifying." [50] Milling efficiency, however, continued to lag for the next several years.

Underlying the operation's difficulties was a lack of experience in commercial mining by company managers. E. W. Barnett, for example, was an engineer with the Alaska Railroad, and Otis Harrington, John Rice, and J. D. Andrews were all known to be prospectors. Given that background, J. G. Shepard roundly criticized the operation, noting that

The management of this property has been very inefficient. Nothing was known as to the value to the ore milled. The value of the tailings was an unknown quantity. A total lack of knowledge of the principles of mill operation was displayed. Mining was poorly done. In short it has been an operation such as might be expected, of men who had no conception of current mining practice.... [A] haphazard operation, such as [has] been carried on in the past, is bound to be a failure. [51]

Robert Heath, who visited the site in 1932, made a similar assessment, which pertained both to the Nuka Bay area generally as well as to the specific operation at Alaska Hills. He noted the following:

The greatest obstacle seems to be lack of men who understand the business and technique of mining. There have been many expensive mistakes made in the past by the pioneer operators that could be avoided by a new company just entering the field.... Practically all of the attempts at mining have been promoted and conducted by men who were trained in other kinds of work. [52]

Despite those difficulties, the Alaska Hills Mines Corporation continued to produce commercial quantities of gold for the next several years. The U.S. Geological Survey's annual report for 1926 noted that

the only [Nuka Bay] mine from which any considerable production of gold was reported was on the Paystreak claim of the Alaska Hills Mines. This mine increased its output considerable over the preceding year and appears to have had an especially successful season, being enabled to run practically without interruption from early in May until November. [53]

The mine remained active in 1927 and 1928; the Seward Gateway during that period faithfully reported the travels of Barnett, Coffey, and others involved with the company. In the spring of 1927, Territorial Highway Engineer R. J. Sommers visited the mill. Shortly afterwards ARC personnel were undertaking "small improvements ... desired by the operators in that district" to the two-year-old trail that connected the mill with tidewater. [54]

By 1928, the Alaska Hills operation was no longer the chief Nuka Bay producer, having been surpassed by the Babcock and Downey (Sonny Fox) mine in Surprise Bay. Production at Alaska Hills that year closed early owing to a snowslide that destroyed "several of the buildings." Perhaps as a result of the slide, "only the usual assessment work was done" in 1929. The following year, the mine apparently continued to be unproductive. [55]

By the summer of 1931, however, the damaged buildings had been either restored or replaced, and the Alaska Hills mine was one of two area mines "producing in a small way," the other mine being the Babcock and Downey outfit. Engineer Earl Pilgrim that year made a thorough investigation of the property for the Territorial Bureau of Mines. He noted that the property consisted of five mining claims: Pay Streak No. 1, Pay Streak No. 2, Pay Streak Extension, Pay Streak Fraction, and Fairweather. Four tunnels were dug on those claims: an upper tunnel, now 125 feet long; a lower tunnel, now 550 feet long; a crosscut tunnel (280 feet northwest of the lower tunnel and at a 370-foot elevation) which was 165 feet long; and a fourth tunnel, at the Emsweiler vein, which was 75 feet long. Pilgrim noted that a crew of three was working at the site that summer; they milled 267-1/2 tons of gold ore and reported a profitable operation. John H. Rice and E. W. Barnett, both of whom had been with the company since the mid-1920s, were the principal company officers. [56]

Production lapsed again after the 1931 season. In 1933, the USGS's annual report noted that "the principal producing mines in the Nuka Bay District" included "the Alaska Hills mine, under the management of E. W. Barnett." But little, apparently, was produced that year, inasmuch as Stephen Capps's 1936 report stated that "only a small amount of mining" had been done since 1931; work in 1936, moreover, was limited to assessment work. [57] For the remainder of the decade, U.S. Geological Survey officials provided bullish (if vague) statements about the mine's activity; in 1937, Alaska Hills was listed as one of three "principal producing properties" in the Nuka Bay area, and in 1939, it was listed as one of the three Nuka Bay properties where "more than casual prospecting" had taken place that year. [58]

The summer of 1940 again witnessed a minimum of activity. That October, however, the property was leased to partners Dave Andrews and John Coffey who, with two others, conducted gold mining and milling operations until late July 1941. The lessees, during that period, milled 160 tons of ore. Inasmuch as the two upper tunnels had caved in, the partnership worked in the two lower tunnels and operated a 1200-foot, two-bucket tramway between one of the tunnel openings and the top of the mill building. The mill, at this time, had a Blake type crusher (as before) but a Union Iron Works ball mill; its capacity was one ton per hour, some 40 percent less than the 1924-era Worthington ball mill had offered. Three men operated at once, two in the mine, the other doing the tramming and crushing. [59]

When Andrews and Coffey ceased operations, mining at the site had been taking place, off and on, for almost 20 years. [60] The property boasted some 900 feet of underground workings, and an estimated $45,000 of gold ore had been extracted, milled, and shipped. After July 1941, however, no known mining operations took place at the site. (The claims were soon relinquished, and unlike many Nuka Bay properties, no new claimants attempted to develop the property during the postwar period.) The site slowly decayed, and by June 1967, the mill had been "dismantled and burned and all the camp buildings were collapsed." Donald Richter, the geologist who investigated the property that year, was able to find just one of the four tunnel entrances (the others were either caved in or covered with snow), and the mid-1920s ARC trail along the Nuka River had been abandoned. [61]

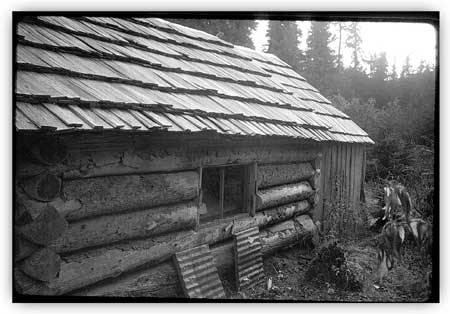

In July 1991, National Park Service personnel visited the property's mill area and main camp as part of the agency's Mining Inventory and Monitoring Program. They made a detailed reconnaissance, spending two days at the site. At that time, the mill consisted of "rusted machinery and artifacts that are partially covered by lumber and metal remains of the collapsed walls and roof of the mill building. Much of the mill machinery is apparently missing." The nearby camp consisted of a log cabin ruin, specifically "sill logs covered with collapsed corrugated metal roofing. Very few artifacts were observed around the camp structure." Agency personnel made no attempt, as a result of the site visit, to nominate the property to the National Register of Historic Places.

|

| Crews from NPS's Mining Inventory and Monitoring Program visited various Nuka Bay-area historic sites during the late 1980s and early 1990s. They encountered hundreds of artifacts--tramways (top), classifiers (bottom), and other items--that remain from the mines' heyday in the 1920s and 1930s. NPS photos. |

Nuka Bay Mining Company (Harrington Prospect)

Shortly after Frank Skeen found gold at what became known as the Alaska Hills Mines Corporation site, Otis Harrington located gold at a site two miles south of Skeen's find. (Harrington was no newcomer to the area; he, along with Frank Case, had claimed the Alaska Hills site in 1917 or 1918 but had subsequently abandoned it.) The new deposit was located 1,470 feet above the waters of Beauty Bay, near the crest of Storm Mountain's southern ridge. Harrington located the quartz vein, thereafter called the Harrington prospect, in either late 1923 or early 1924.

Inasmuch as Harrington apparently worked alone, development proceeded slowly. When geologist H. H. Townsend visited the site in 1924, the deposit sported several open cuts and one timbered shaft. During the year that followed, "very little development work" took place at the so-called "Nuka Claims;" the only improvement was a 20-foot tunnel. Harrington, by the summer of 1925, had taken a partner and was planning to install a small mill that winter. (News reports at the time noted that an Ellis ball mill was on its way to one of the area's mines; it may have been headed for Harrington's property.) The geologist that visited the property, however, told him that there was "not sufficient ore of a rich value in sight to warrant this expenditure." Perhaps on the basis of that advice, no mill was installed. [62] Harrington soon turned his interest in the property over to Denis Hurley. Hurley's interest in the site, however, was brief; that October, he relinquished all rights at the property to Calvin M. Brosius.

Brosius, a prominent Seward resident, was a lumber and building materials dealer. He had no direct interest in mining. Having supplied many area miners, however, it is not surprising that he became active in mining operations. In addition to the Nuka Bay property, he and partner Bill Knaak also had interests in mines at Crown Point (near Lawing, north of Seward) and on Stetson Creek (just south of Cooper Landing). Knaak was a miner by profession; he did most of the development work, while Brosius's support appears to have been primarily financial. [63]

The Nuka Bay property lay idle until 1928, when "some work" took place there. By the following year, Brosius and his associates had established the Nuka Bay Mining Company. Brosius let a contract to Alec Erickson to dig 100 feet of tunnel at the site. Another worker soon joined him. By year's end, "about 95 feet of tunnel was driven" and a mill (probably a "small gasoline-driven Gibson mill") had been delivered to a location "near the portal of the tunnel," but the mill was never operated. Access to the site was via the ARC trail for about three-quarters of a mile north from Beauty Bay; at that point stood a Nuka Bay Mining Company-owned log cabin, from which a 3,400-foot trail led eastward (and up a steep slope) to the mine. [64]

Development work appears to have continued at the mine for the next two years. By the summer of 1931, Earl Pilgrim noted that the "principal owners" of the "Nuka Bay Mines Company" were Brosius and Mrs. E. B. Weybrecht. The mine site consisted of three lode claims: Nooka, Nooka Extension, and Nooka No. 1. The complex consisted of the now-abandoned upper tunnel, at elevation 1,470 feet, where Harrington had carried on his early work; a lower tunnel, nearly 400 feet long, at elevation 1,140 feet; and an open cut at elevation 1,240 feet. An upper camp was located at elevation 1,200 feet. (A lower camp was not mentioned, but it probably consisted of the log cabin, and perhaps ancillary buildings as well, at the ARC trail junction.) The mill was situated at the mouth of the lower tunnel, where most of Brosius's activity appears to have taken place, but according to a 1936 report, the mill was probably never used. [65]

After 1931, the operation lapsed into idleness. In 1933, Charles Goyne may have spent time at the site (his Surprise Bay property was being worked by others that year), and plans were also announced to have miner John Soble drive a 30-foot tunnel there. The tunnel, however, was apparently never begun, and no further development work took place at the site. Brosius, who still controlled the property, continued to perform annual assessment work until 1941. The following year, Brosius was killed in an accident at his lumber store, and the claims were apparently relinquished soon afterward. [66] In 1968, two new mining claims (North Beauty No. 1 and No. 2) were made at the property, and the following year the Snowlevel claim was located, possibly at the same site as the North Beauty claims. The owners, all of whom held other area claims, were Donald Glass of Jamestown, Ohio; Martin L. Goreson of Seward; J. L. Young of Kenai; and Ray Wells, address unknown. No development work took place as a result of these claims. The two North Beauty claims were abandoned, and by the early 1980s the Snowlevel claim had been relinquished. [67]

The camp, last actively used in 1931, deteriorated quickly. In 1936, the mill was "exposed to the weather and in bad condition." By 1967, Donald Richter noted during a site visit that "no buildings remain standing in the prospect area, and the tailing pile at the portal of the [lower] exploration tunnel is largely grown over with alder." The portal of the tunnel, with its "410 feet of underground workings," was still open and accessible. The trail from the ARC trail to the camp, however, was "almost completely covered with growth" and the cabin where the trail commenced was in a collapsed state. [68]

In July 1991, the mine and camp were visited by National Park Service personnel as part of the agency's Mining Inventory and Monitoring Program. As part of their detailed reconnaissance, they noted that "the site consists of a large concentration of mining equipment and machinery, an adit with associated ore cart track, a large spoil pile, and two prospect pits." No buildings were found, and artifacts were "composed mainly of tool fragments and industrial debris." This group, like Richter 24 years earlier, was unable to locate the upper tunnel. A few days later, members of the group visited the collapsed log cabin, at the base of the trail, that may have served as the lower camp. They found that "some courses" remained on all four walls; no roof existed, however, and the logs were "punky and sodden." A few associated artifacts were found nearby. Agency personnel made no attempt to nominate either property to the National Register of Historic Places.

Nukalaska Mining Company

The Nukalaska Mine, located on a near-vertical, north-facing slope high above Beauty Bay, was the last significant prospect in the Nuka Bay area to be located, and also the last to be commercially developed. Al Blair, who had previously developed the Blair-Sather prospect in Yalik Bay, discovered the vein and made three mineral claims in 1926. He appears to have remained active at the site through the summer of 1927. [69] Soon afterward, however, he lost interest in the area. In September 1931, veteran prospector Robert Hatcher (who was also active elsewhere in Nuka Bay) and fellow Sewardite T. S. McDougal claimed the vein but did little if any site work. [70] Hatcher apparently hired Ray Russell, who developed the site sufficiently to interest mining developer M. B. Parker from Hollywood, California, along with Edward P. Heck of Fellows, California and F. G. Manley of San Francisco. The group bought the property in early 1933. By the end of that year, a government geologist was probably referring to this site when he noted that "rumors were afloat of a number of deals pending with a view to the undertaking of more intensive work." [71]

By early 1934, Parker had formed the Nukalaska Mining Company. Commercial development proceeded immediately. Geologist Stephen Capps noted that the improvements included:

the construction of 1-1/4 miles of road from the beach to the camp and thence to the lower terminal of the tramway, 2,000 feet upstream from the mill; a 3,500-foot 2-bucket 7/8-inch cable gravity tramway from the mine to the lower terminal...; and a mill, office, bunk houses, cook house, and blacksmith shop. The [flotation] mill is equipped with jaw crusher [and] ore bin, with a capacity of 1 ton an hour.... [72]

The original or western quartz vein, according to Capps, "crops out on the crest of a high, rugged ridge" at elevation 2,280 feet and "is so steep as to be difficultly [sic] accessible." To mine it, an adit (or tunnel) was driven into the cliff face 200 feet below the outcrop. Workers found the vein after digging into the mountain for 230 feet; once encountered, they began crosscut tunnels that, by August 1936, had been driven 175 feet to the west and 200 feet to the east. Active stoping was also carried on; in one section, stopes reached 80 feet above the adit level. At the mine portal stood a bunkhouse, ore bin and tram terminal, with an enclosed blacksmith shop. [73]

Development proved so promising that in 1935, the company staked 15 additional mining claims. The size of the crew also increased; in 1934, the crew was evidently fairly small, but by 1936 the company had 20 workers at the site, enough for one daily shift in the mine and three shifts in the mill. [74] Workers in 1935 included Don McGee and Amos Buffin; company managers included Parker, his assistant Z. N. Marcott, and Ray Russell. [75]

During 1936 and 1937, good news prevailed at the Nukalaska Mine. After an August 1936 visit, for example, geologist Stephen Capps noted that "the material milled was yielding about $100 to the ton in gold, notwithstanding the fact that about two-thirds of it was country rock that had to be mined along with the vein quartz." Based on such promising results, a crew numbering either 19 or 20 people (including one woman) worked a six-month season, from May to November. [76]

Despite the company's success, managers recognized that the existing system of ore removal needed to be changed. Snowslides each year destroyed the 2,000-foot road that connected the camp with the lower tramway terminal; nearly every year, moreover, snowslides swept the towers away from the tramway that connected the mine entrance to the road terminus. The destruction caused by those events limited the milling season to three months annually. [77] In order to circumvent those problems, managers by the end of 1937 unveiled plans to drive a new, eastern tunnel "on the opposite side of the creek from the old workings." [78] Work both that year and in 1938, however, was limited to the western workings.

In June 1938, a fire "destroyed part of the buildings comprising its surface plant;" the milling plant (perhaps the only building involved) was "completely destroyed." The company, as a result, gained new management; the new managers, who resided in Los Angeles, included W. V. (Vince) Conley, President; W. R. Foster, Treasurer; and J. S. Mathews, Secretary. Mining was suspended for the remainder of the year. [79]

That winter, another tragedy struck as "heavy snow slides ... damaged some of the surface equipment at the Nukalaska property." The twin disasters forced the company to lay off two-thirds of its workers. The remainder of the work force soldiered on, however, and "in spite of the delays required for these repairs, the operators [in 1939] were able to extend the long crosscut they had been driving about 350 feet." By year's end, the length of the crosscut tunnels that branched off the main, 230-foot tunnel reached 200 feet (to the west) and 490 feet (to the east). The western tunnel was abandoned thereafter. [80]

On June 1, 1940, the company began to develop the long-planned eastern or lower tunnel, the portal of which was at elevation 1,300 feet. Work on the new tunnel continued all summer and by early September, 1,250 feet had been dug. [81]

By the following July, 90 feet had been added to it. At its portal stood a compressor shed; between there and the mine camp stretched a 2200-foot aerial tramway with a single 5/8" cable and a 3/8" carrier cable. A 1941 visitor to the camp noted that "safety conditions are none too good: the men ride to and from work on the power tram on a two-wheel carrier, which almost touches the ground in two places, and the carrier cable drags on bedrock in several places forming grooves." The tram to the mine's western tunnel workings, described as a 3,700-foot aerial tram with a double 7/8" cable, was no longer used but had not been removed. [82] The camp and the surrounding area had changed little since the mid-1930s. The main camp consisted of three wooden buildings–the office, a bunk house, and cook house–plus two tents. A machine shop was located 300 feet above the camp; at the beach, 1-1/4 miles northeast of the main camp, stood a cabin and a small storehouse. Miners lived in the bunkhouse, the tents, and the beach cabin; the crew in 1940 numbered 12 to 15 people, which included a tram operator, a blacksmith, and site manager Vince Conley. Two men lived with their wives, and one of the couples had their two young children in residence. [83]

During the summer of 1941, mining was concentrated on a western extension of the eastern workings. According to a mine resident, however, production had to be curtailed because of falling rocks and because so much water was encountered that fuses could not stay lit. After that season, production shut down for a decade or more. During the 1950s some Hawaiians, locally called the Honolulu group, tried to rework the mine but the venture was apparently short-lived. [84] The site appears to have lain idle until 1969, when J. L. Young, V. J. Wright, and Ray Wells claimed the property as the Lucky Devil Mine. No known production took place there, however; they last performed assessment work on the property in 1971, and there have been no mining claims on the property since then. In 1976, the property was assessed at a rock-bottom valuation of $250. [85]

The Nukalaska Mine, in retrospect, was one of the largest mines in the Nuka Bay area. Although activity took place at the site off and on between 1926 and the 1950s, it appears to have operated commercially only from 1934 until 1938. (No commercial production took place after 1938 because no mill was in place.) During that time, two widely varying estimates have emerged of its gold yield. J. C. Roehm, in 1941, reported that "the total production ... was reported at 2,320 tons of ore milled" and a "total production figure of $116,000." But Donald H. Richter, who based production figures solely on years of activity and an assumed volume of 200 tons of gold ore per year, estimated the mine's yield to be approximately $35,000. Based on the size of the crew, the length of the workings, and (admittedly anecdotal) descriptions of the ore's value, Roehm's yield appears to be the more accurate of the two. [86]

This property, along with most sites in the Nuka Bay area, has significantly deteriorated over the years. When Richter visited the site in June 1967, he wrote that the

road from Shelter Cove to the mill & camp ... was obscured by vegetation, and the mill equipment and camp buildings had been destroyed by man and weather. An aerial tram, however, was still standing; it has a vertical drop of about 1,900 feet and extends from the mine adit to a terminus three-eighths of a mile west of the mill. Southwest of the mill the remains of another aerial tram, or possibly one that was under construction in 1940, extends up the east face of the mountain.... The mine workings were inaccessible owing to caved timbers at the portal. Four hundred feet west of the mine ... a small bunkhouse still stands cabled onto a narrow ledge. [87]

Despite its relatively advanced state of decay, the remaining site evidence has intrigued visitors. By the early 1980s, a National Park Service report noted that "the access road to the complex is extremely overgrown, and the effects of past mining activities are not readily visible." Even so, archeologist Harvey Shields called the site a "Jewel in the Jungle." At the old camp, he noted that

Because of the underbrush and overgrowth it was difficult to get a truly accurate idea of what was there. However, several collapsed buildings were seen along with many pieces of large equipment such as generators, a possible flotation cell, a Model A Ford, and an assay office. This was in addition to many smaller tools and household items.... Cables could still be discerned high overhead that relate to the system bringing ore down from the mine. The actual shaft was not located but local knowledge suggests that it was intentionally sealed off with a great deal of equipment stored inside. [The complex] has a great deal to offer the National Park Service and the nation. Most obviously it is a time capsule for understanding early to mid-twentieth century mining in Kenai Fjords.

The property's value was reflected in Kenai Fjord National Park's General Management Plan, issued in July 1984. The plan noted that "the abandoned mine facility at Shelter Cove is an excellent representative of the type of mining operation which occurred in the Nuka Bay area." [88]

In 1989, a team from the NPS's Mining Inventory and Monitoring Program visited the mill and camp area. The description of the area is more accurate, if perhaps less dramatic, than that provided in 1983:

The Nukalaska mill and camp location consists of several collapsed structures with a large inventory of associated, in-place artifacts dating from the 1920s and 1930s. Buildings, for the most part, are in a state of total ruins. Several structures appear as diffuse lumber scatters with foundation remnants. Distinct but collapsed structures include three plank-framed cabins, a plank-framed cookhouse, a powerhouse/blacksmith shop, and a mill building. Associated with these last two features is a huge inventory of in-place artifacts and equipment associated with the processing of gold-bearing ore materials. Other associated features include a collapsed shed, an equipment scatter, a stationary engine, and a barrel scatter. Although the structures are in poor condition, site integrity is exceptional [89]

Personnel spent several days making a detailed description of the property. In the evaluation that followed that visit, agency personnel noted that the site was "probably eligible" to the National Register of Historic Places. A year later, historian Logan Hovis wrote a "Determination of Eligibility" report in which he concluded that the mine and camp was eligible for listing on the National Register under criteria A, C, and D. That report was forwarded to Alaska's State Historic Preservation Officer, Judith Bittner. On April 24, 1991, Bittner agreed, noting that "we concur that [the site is] eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places under the stated criteria."

During the summer of 1991, NPS personnel returned to the area and visited the Lucky Devil Mine (i.e., the west workings of the Nukalaska Mine). The site included a collapsed cabin with associated artifacts, a pit of unknown function, an unrecorded adit, and a nearby cable tram. It has not yet been evaluated for National Register eligibility. [90]

Glass and Heifner Mine (Earl Mount and Little Creek prospects)

In September 1923, shortly after Frank Steen's "discovery" attracted scores of miners to the area, Eric Burman and H. Carlson found four promising quartz veins near the head of Beauty Bay and dubbed it the Little Creek property. The site of their find was along Ferrum (Iron) Creek, just 0.9 miles from tidewater and less than three miles away from Frank Steen's Alaska Hills claim. The pair began developing their property that summer; they excavated a large number of open cuts, dug a 20-foot tunnel, and roughed out a trail between the claim and the bay. [91]

Carlson soon lost his interest in the property, and in June 1928 Burman sold his rights at the site to Earl Mount, a longtime Seward resident and proprietor of the Seward Leather Works. [92] In the summer of 1929, Mount hired a miner to help develop his property. The claimant periodically visited the prospect but probably spent little time there. [93]

By 1931, Mount had staked two claims–Little Creek No. 1 and Little Creek No. 2–and either he or his employees had performed development work on four of the property's quartz veins. On the vein that had been developed in 1924, a tunnel had now been extended another 30 feet. The other three veins, located to the south of the tunnel, featured open cuts and trenches. A small camp (of unspecified composition) had been established not far northeast of the tunnel. [94]

By the following year, Mount had staked an additional claim. Geologist Stephen Capps, who investigated the property in 1936, noted that Mount began leasing the property to others in 1932; either he or the lessee sank a 15-foot shaft that year. [95] For the next two years, Jack Morgan, Guy Kerns and other lessees extended the existing tunnel another 400 feet and completed a raise that extended to the surface. The lessees, however, failed to find enough gold to justify the purchase of a mill, and in 1934 they abandoned their lease. For years afterward, Mount continued to hold the property but limited his involvement to annual assessment work. [96] The claim was eventually abandoned.

In 1958, Seward residents William Knaak and Frank Cramer relocated the property, calling it the Beauty Bay Mine. They erected a cabin, built an arrastra, and treated 500 to 600 pounds of ore to determine its value. Cramer, a barber, and Knaak, a World War I veteran, carpenter, and longtime miner, attempted to develop it for the next few years. Knaak reportedly found several more ore bodies and remained active with development work until 1962, but the partners did not commercially develop the property. [97]

In 1965, two men from Jamestown, Ohio, geologist Don Glass and pharmacist Max Heifner, agreed to purchase the property for $52,500. They began making payments that year, and in 1968 they completed the purchase and secured a warranty deed from the former claim owners. Glass visited the property every year for more than a decade. Beginning in 1965, Glass worked the Beauty Bay claim. Then, in 1968, he staked the Glass-Heifner No. 1 and No. 2 claims. [98]

The new partnership reinvigorated activity at the mine. Heifner noted that soon after the partnership began purchasing the property, Glass "cleared out an ad hoc [aircraft] runway along the beach and made it sufficiently long by clearing out a lot of alders that grew above the high tide line." [99] He also widened the mile-long trail between the beach and mine with a bulldozer. In 1965, Glass purchased a used four-foot ball mill from the state and installed it on the property. By 1967 he had also lengthened the existing cabin by 15 to 18 feet and had added a machine shop. In addition to the ball mill, the milling equipment consisted of two jaw crushers and a concentrating table. By 1973, the partners had reportedly invested $230,000 in the operation. [100]

Records are not available regarding the amount of ore milled from the site, but it appears to have been a small-scale commercial operation. Donald Richter noted in 1967, for example, that "a limited amount of ore" had been mined, and the Seward City Council, in 1974, stated that $27,000 in gold had been extracted from the site during the previous year. George Moerlein, asked to assess the operation in July 1976, stated that the partners had produced "less than 100 tons" of ore over the last 12 years (although he also stated that "to date, the property has no recorded production"). He assessed the property, exclusive of improvements, at $30,000; this was more than twice that of any other Nuka Bay mining property. Heifner, in a recent interview, noted that the partners were "fairly successful" but that they didn't get rich. [101]

Glass returned to the site each year until 1979. By 1981, the partners had leased their property. They later sold the mine on contract to Harry Waterfield, who mined and performed assessment work. After Waterfield's death, Glass and Heifner again claimed the property and continued to hold it until 1994, when they sold it to Seward resident Tom DeMachele, the current claimant. Because mining has remained active in recent years, there are still two valid unpatented mining claims at the site: Glass-Heifner No. 1 and Glass-Heifner No. 2. [102]

Although development activities took place in the mid-1920s, early 1930s, and late 1950s, commercial mining took place only after 1965. Recent activity, moreover, has diminished whatever historic value the site may have acquired from pre-World War II developments. Shields, in 1983, noted that recent mining activities had "pretty much obliterated the traces of the early mining activity." [103]

In August 1989, a National Park Service team visited the site as part of the Mining Inventory and Monitoring Program. A report generated after that visit noted that the camp still contained all the buildings that had been constructed in the 1960s save the bunkhouse, which had burned. It also stated that "scattered pre-1940 artifacts were observed and recorded, although they have been displaced from their original contexts and integrated into the modern venture." Based on that evidence, investigator Logan Hovis stated that "it seems likely that this site is not eligible for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places," and no attempt was made to prepare such a nomination.

Miscellaneous Sites, Beauty Bay

Little is known about other mining sites adjacent to Beauty Bay. Somewhere along the bay's west side, perhaps midway between the head of the bay and Shelter Cove, was a prospect worked by Robert Evans. Evans, as noted in Chapter 6, was a homesteader who lived in a cabin near present-day McCarty Fjord. Nuka Island resident Josephine Sather recalled that when Evans "first came to this part of the country he did assessment work for others. Later he hunted seals, and finally he took to prospecting." Records related to Evans are few, but a May 1935 article from the Seward Gateway suggests that he remained at one site for an extended period:

Bob Evans came to town this morning riding his Speedboat "Nuka Bay Comet." It was his first visit from the gold camp in two and one-half years. He is doing development work on gold claims owned jointly by Mrs. P. C. McMullen and himself, driving a long tunnel into a rich lead. Mr. Evans, veteran prospector and amateur photographer of exceptional ability, is in town for a brief vacation and for supplies. [104]

Evans probably began working the claim in late 1931 or 1932; how long he worked the site is not known, although other comments by Mrs. Sather suggest that he may have intermittently returned to the site until just before his death in 1941. [105] Unfortunately, however, no area visitors ever noted the specific site of his claim, and the site may now be indistinguishable from the surrounding terrain. Evans probably never built a cabin at the site, preferring instead to travel there from his East Arm cabin, and inasmuch as no records establish specific development work, he probably never installed milling equipment.

Scattered sources refer to other ephemeral prospecting ventures. The Homestead and Anchor Group, purportedly located between the Alaska Hills Mine and Nuka Bay, was located shortly after Skeen's find in 1923, and it was visited by geological investigators in both 1924 and 1925. A 15-foot tunnel was driven on the property in 1924, but the prospects were so poor that it was probably abandoned after 1925. So far as is known, no recent investigators have rediscovered this site.

Two historic cabins were constructed on the shore of Beauty Bay which are not known to be related to a mining venture. Earl Pilgrim noted both during his 1931 investigation; both were located at the head of the bay. One, at the base of the trail to the mining development along Ferrum Creek, was probably built by Earl Mount (or someone in his employ) after Mount acquired the mining property in 1927. A field examination notes that the other cabin, at the northeast end of the bay, is located at the southern end of the old wagon road; in all probability, therefore, it was built in conjunction with either the Alaska Hills or Nuka Bay properties. Geologist Don Glass may have obliterated Mount's cabin as part of his airstrip development during the 1960s. If not, it may still exist, though in deteriorated condition. The other cabin is now just above the tidal zone, the land having subsided during the March 1964 earthquake; only a few base logs remain to identify it. [106]

Nuka Bay Mining Sites: North

Arm

Rosness and Larson Property

This property is located on the west side of North Arm, more specifically two miles northeast of Moss Point and surrounding a small cove. The mountain slope, in the area of the workings, juts up fairly steeply from the water's edge. All human activity at this site took place within several hundred yards of tidewater.

This site is one of the first places where minerals were recorded in the present park boundaries. When Ulysses S. Grant made the area's first geological investigation in 1909, he noted that a four-man prospecting party–Daniel Morris, James Sheridan, George W. Kuppler, and John H. Lee–had located several pyritized dikes at the site and staked a mineral claim. Grant recorded five mining sites that year along the park's southern seacoast; this site, however, was the only one that was later developed. [107]

The claim made by Morris and his fellow prospectors was quickly abandoned, and the property lay idle until Skeen's find brought renewed interest to the area. Soon afterward, "old John Gillespie" (as he was known locally) rediscovered the site. By the summer of 1924, he had teamed up with Albert Rosness. [108] An investigator that year noted that the partners were pursuing a quartz vein that was exposed at tide level, but "little exploratory work" had been done at that time. By the following summer, "a small amount of work" consisting "mostly of surface trenching" had taken place at the site. But the site investigator that year was pessimistic to an extreme; he stated that "nothing of any importance was discovered," and furthermore predicted that "it is not likely that the prospect will ever prove of commercial value." [109]

Nothing more was heard about the property for the next several years. By 1931, however, Gillespie had abandoned his interest in the site; Rosness's new partners were Josie Emsweiler and Frank Larson. [110] Investigator Earl Pilgrim, who visited the area that July, noted two men working there. At the quartz vein located in the southwest corner of the cove, they had erected a bulkhead to prevent waves from entering the workings. They had mined the decomposed surface material and hoisted it up to an ore bin by means of a trolley and windlass. Thirty feet to the south, a 28-foot tunnel had been dug; near the end of it, a winze had been sunk to a depth of 27 feet. Two hundred and fifty feet northwest of the beach workings, at an elevation of 110 feet, was a 20-foot tunnel. Seventy feet to the north was an open cut; below the cut was a 105-foot tunnel. In order to process the ore from the three tunnels and the various surface croppings, the partners had erected a gasoline-driven Ellis mill; the mill, located just below the 20-foot tunnel, was small, having a capacity of four tons per day. In addition, the site featured a small frame residence and two tents. [111]

By 1932, Emsweiler's interest in the property had been replaced by that of Nuka Island resident Peter Sather, and the mine continued to operate on a commercially-productive basis for another year. Donald Richter, who chronicled the site's history, was skeptical about the level of commercial activity, noting that the property "apparently produced some gold" during the 1931-33 period. Using rough calculations, however, he estimated a total production of about $15,000 in gold during that biennium. [112]

The property was probably not active after 1933, and by 1967, when Richter visited the site, he described the mill and camp buildings as "ruined." [113] In May 1969, the property was restaked as the North Nuka No. 1 and No. 2 claims by J. L. Young, V. J. Wright, and Ray Wells. The trio, however, apparently made no improvements to the site, and they abandoned their yearly assessment work after 1971. The site has lain idle since that time. [114]

In July 1991, National Park Service personnel visited the property as part of the Mining Inventory and Monitoring Program. The site that year featured "a power plant with a mill, two adits at tide level, an adit on a hillside, a penstock, a dam, and scattered artifacts." Power generating equipment was located on the floor of the ruined power plant, mining equipment was found outside of one of the adit portals, and scattered mining artifacts were found in the intertidal zone. The crew was not, however, able to locate either the cabin or the tent frames that comprised the former camp. Perhaps based on the poor condition and relative paucity of artifacts, the agency made no attempt to nominate the property to the National Register of Historic Places.

Kasanek-Smith Prospect

Southeast of the Rosness and Larson property, and directly across North Arm, is a small, unnamed cove. On a point of land, about one-half mile north of the cove, Alec Kasanek [115] and Jack Smith found a promising quartz vein in 1924 or early 1925. They called their claims the Butter Clam group. "Alex Kasenek" registered four claims in July 1925, and by September a tunnel 20 feet long had been dug near the high tide line. But ore values were apparently low; visiting geologist J. G. Shepard remarked that "the prospect does not seem to warrant further investigation." [116]

The partners, however, decided to press on. A Seward Gateway article in December 1925 stated that the pair were "remaining in the district over the winter." They remained active as late as 1927; that June, Kasanek was listed as one of several mining men who "will carry on development work on their various properties," and Smith was also at "the quartz camp" that year. The ever-bullish local newspaper stated that the partners were "developing one of the best looking properties in the Nuka Bay field." [117] Expectations, however, evidently exceeded reality, and by 1931 the property had been abandoned. The tunnel, at that time, was described as being 26 feet in length, which suggested that the partners undertook little development work after September 1925. (Based on evidence gained during a 1976 visit, the partners may also have dug out a surface trench above the adit; see discussion below.) Pilgrim noted a cabin, evidently associated with the tunnel; located in a small cove a few hundred feet south of the tunnel, it was probably built about 1925. So far as is known, no mill was ever brought to the property. [118]

Donald Richter, during his 1967 investigation, did not visit the property. But in July 1969, three prospectors–J. L. Young, V. J. Wright, and Ray Wells–established the Rainy Day claim there. They maintained yearly assessments until 1971, then abandoned the claim. George Moerlein, who visited the property in 1976, found "a 20 foot adit along the shore" and, at an elevation of 60 feet, "a shallow trench on a 3 foot wide quartz vein." [119] NPS personnel have since located the adit but no one, so far as is known, has visited the cabin site. The area has not been evaluated for National Register of Historic Places eligibility.

Robert Hatcher Prospects

Robert L. Hatcher was, according to one source, "one of the best known prospectors and miners of Alaska." Born in 1867, Hatcher first located Kenai Peninsula claims in 1910, near Moose Pass. Later, he staked the properties that became the well-known Independence Mine, north of Palmer. (Hatcher Pass, two miles southwest of the mine, is named in his honor.) During the mid-to-late 1930s, he returned to the Kenai and developed prospects on Palmer Creek (south of Hope) and Slate Creek (northeast of Cooper Landing). He remained active well into his dotage; at age 76, he located a new property between Lawing and Moose Pass. More successful than most, Hatcher was one of thousands who spent his life in search of gold and other "colors." [120]

From the mid-1920s through the early 1930s, some of Hatcher's energy was directed toward a series of prospects along Nuka Bay's North Arm. He located five or more properties, none of which proved commercially successful. His first prospect was apparently located in 1923 or 1924; a geologist visited the site, on the east side of the arm, in the summer of 1924 and noted that Hatcher's work consisted of a single open cut and a nearby adit.

By the following summer, Hatcher had not improved either site, and the geological investigator was pessimistic that future adit work would prove fruitful. Perhaps as a result, Hatcher pursued new properties. During the summer of 1925, he and a partner known only as Mr. T. McDonald staked some "quartz ground" in a valley on North Arm's western side. The site, opposite Pilot Harbor and three-quarters of a mile upstream from tidewater, contained two huge waterfalls, ten feet wide and more than a thousand feet high. So far as is known, Hatcher and McDonald never developed this claim. [121]