|

Alaska Subsistence

A National Park Service Management History |

|

Chapter 8:

NPS SUBSISTENCE MANAGEMENT ACTIVITIES, 1990-PRESENT

A. Status of the NPS Subsistence Program, 1990-1991

As noted in Chapter 6, a major action of the various NPS subsistence resource commissions during the late 1980s had been the submission of hunting plan recommendations. These recommendations had been submitted, for the most part, in 1986 and 1987, and representatives of the Interior Secretary had responded to those submissions between March and May 1988. Inasmuch as these submissions had comprised the first official exchange between the SRCs and the Interior Secretary's office, it is perhaps unsurprising that the Secretary accepted some recommendations, rejected others, and modified still others. The Secretary's office, it appears in retrospect, applied a strict-constructionist approach in its interpretation of the subsistence regulations.

In general, the submission-and-response process was valuable in an educational sense, because it clarified specifics of regulations whose interpretations had not previously been meted out. In many instances, SRCs tacitly accepted the Interior Secretary's opinions. But regarding a number of issues, SRC members patently disagreed with the Secretary's rulings and vowed to re-submit either the same or similar recommendations all over again. Such was the state of affairs during the waning months of the 1980s.

Little change was in evidence during the first year or two of the 1990s. SRC activity, on the whole, seemed sluggish (see Appendix 5); during 1990, four of the state's seven SRCs did not meet, and one other SRC, from Aniakchak National Monument, met but was unable to muster a quorum. (The Denali SRC, normally active, stayed dormant that year; chair Florence Collins opted out of a proposed October 1990 Commission meeting in order "to keep the Park Service from spending money for a meeting we felt could accomplish little.") [1] The following year, activity picked up considerably—five of the seven SRCs were able to hold a legally-constituted meeting—but between January 1990 and the fall of 1991, few official expressions of opinion emerged from the various SRC meetings. During this period, most of the SRCs mulled over recommendations that the Interior Secretary had rejected back in 1988. [2]

|

| Alaska's NPS superintendents, gathered for a 1991 conference. They included (left to right): Ernest Suazo (BELA), Karen Wade (WRST), Andy Hutchison (LACL), Roger Siglin (GAAR), Alan Eliason (KATM), Ralph Tingey (NWAK), Russ Berry (DENA), Marv Jensen (GLBA), Don Chase (YUCH), Anne Castellina (KEFJ), Clay Alderson (KLGO), and Mickie Hellickson (SITK). NPS (AKSO) |

The only official SRC recommendation that found its way to the Interior Secretary's desk during 1990 or 1991 was a proposal that had been finalized years earlier. This proposal, a combined recommendation of the Cape Krusenstern and Kobuk Valley SRCs to combine resident-zone communities within the boundaries of the NANA Regional Corporation, had been readied for submission to the Interior Secretary back in 1986; but for reasons that were discussed in Chapter 6, the proposal had gone into bureaucratic limbo. It resurfaced because of a chance question posed by Walter Sampson, the Kobuk Valley SRC head, at the SRC chairs' meeting in December 1989. Sampson, angry at NPS officials, claimed that the incident "causes me to question the commitment of some of the personnel in your agency" regarding the SRCs; furthermore, it "emphasizes the inadequate support that we have received from NPS personnel over the years." NPS officials, however, tactfully defended their actions. A year later, on March 12, 1991, the proposal was officially submitted to the Interior Secretary. [3]

One reason for the relative paucity of activity—which, in large part, was a continuation of the state of affairs that had existed during the mid- to late 1980s—was the relative lack of staff and budget that the NPS provided for subsistence program management. As noted in chapters 5 and 6, the agency's Alaska Regional Office had hired a full-time Subsistence Coordinator in early 1984, and during 1987-88, the addition of new (if short-term) staff members brought about the establishment of a separate Subsistence Division. Between 1989 and 1991, as noted in Chapter 7, the regional office's subsistence staff swelled from one to six. [4] (See Appendix 3.) At the field level, however, subsistence-related matters continued to be handled as one of many collateral duties of a park's superintendent, management assistant, chief ranger, or resource management specialist.

The lack of staff time that could be devoted to subsistence matters, plus the small ($10,000) budget allotted to each of the SRCs, meant that subsistence concerns maintained a relatively low profile among park priorities. Moreover, few within the agency were in a position to advocate for the needs of park-area subsistence users. This state of affairs caused a state of widespread restiveness among some SRC members; one member later noted that the NPS during this period was "trying to eliminate subsistence as soon as possible," while another charged that "Any component of a hunting plan which is outside the scope of what NPS feels 'could prove detrimental to the satisfaction of subsistence needs of local residents' [is] unilaterally rejected without full consideration." [5] SRC members constructively reacted to the situation by calling for an increase in the SRC budgets, for an increase in the number of yearly meetings, [6] for new opportunities to communicate with other SRCs, [7] and for funding to travel to meetings of the State Game Board, the newly-established Federal Subsistence Board, or other regulatory bodies. [8] But agency officials, in response, typically denied these requests. The frustration level was such that SRC members occasionally resigned their positions with a strongly-worded letter to the agency, while those who remained in their positions sometimes complained about the intransigence and insensitivity of NPS officials, both at the park and regional levels. [9]

As noted above, a troubling undercurrent during this period—and an underlying concern of the subsistence community ever since ANILCA's passage—was that NPS officials were trying to curtail subsistence use in the various Alaska park units. During the 1970s, when Congress considered various Alaska lands questions, both Natives and non-Natives openly worried that subsistence, in the face of technological change and widespread economic development, might be on the verge of extinction. In May 1979, for example, House Interior Committee Chairman Morris Udall noted,

... change is occurring very rapidly in rural Alaska and it seems to me that as rural Alaskan people become more dependent on a cash economy, fewer and fewer will be dependent on subsistence resources and even fewer would qualify under our priority system. [10]

Despite that worry, however, the language contained in ANILCA (as noted in Chapter 4) clearly told rural Alaskans that the federal government would "protect and provide the opportunity for continued subsistence uses on the public lands by Native and non-Native rural residents." Furthermore, the bill's access provisions ensured that subsistence users would continue to "have reasonable access to subsistence resources on the public lands," and that methods of access could legally include "snowmobiles, motorboats, and other means of surface transportation...." [11]

During the years that followed ANILCA, Udall's prediction turned out to be wide of the mark; "living off the land" continued to a viable, sought-after lifestyle choice by some rural-based non-Natives, and for many Natives, keeping a subsistence-based lifestyle became an increasingly important aspect of cultural identification. Subsistence, it was clear, was not going to fade away any time soon. From time to time, however, frustrated SRC members charged that the NPS was trying to hamstring subsistence opportunities, and some subsistence users—mindful of traditional policies in parks outside of Alaska—may have felt that the agency's long-term goal was to eliminate subsistence activities in the parks altogether. Agency officials, in fact, had no such intention, but the NPS's perceived intransigence on various subsistence policy matters implicitly suggested that the agency had little interest in either supporting or encouraging subsistence uses.

B. NPS Subsistence Program Changes, 1991-1993

The McDowell court decision of December 1989, as noted in Chapter 7, had a profound, dramatic effect on how subsistence management activities throughout Alaska, and to a large extent, the changes that the McDowell decision wrought inevitably began to affect the process by which the National Park Service administered subsistence activities on its parklands. The most obvious result of McDowell took place on July 1, 1990, when federal officials assumed responsibility for overseeing subsistence activities on the three-fifths of Alaska's land mass that was administered by various federal land management agencies. The State of Alaska, as has been stated, vociferously opposed this action and attempted, through various means, to regain management authority. Alaska's three-man Congressional delegation, for its part, also preferred a unified system of state management rather than a strong federal management role. The delegation, however, recognized that the federal government, at least in the interim, needed a secure funding base for its management efforts. To that end, therefore, Senator Ted Stevens earmarked $11.3 million in Fiscal Year 1991 appropriations "to fund the management of subsistence hunting and fishing on federal lands." Much of that funding allotment was funneled to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which was the lead agency administering the federal government's subsistence program; portions of it, however, were distributed to the National Park Service and other federal land management agencies. [12]

As noted above, some of the NPS's budgetary allotment was directed to the Alaska Regional Office, and the agency was able to hire three new Subsistence Division personnel in 1991. But parks were the primary recipients of the NPS's allotment. [13] By November 1990, at least one Alaska park superintendent had told his SRC that federal assumption would result in new subsistence staff, and by March 1991, other park units had received word that new Subsistence Specialists would be joining the ranks. [14] (See Appendix 3.) But subsistence staff was not the parks' only priority, so when Lou Waller, in conjunction with other regional officials, decided to allot funds to each park unit in which subsistence activities took place, superintendents reacted in a variety of ways. Some, as suggested above, hired new individuals to manage park subsistence activities, but at other parks, existing staff—chief rangers, management assistants, or cultural resource specialists—readjusted their duties to accommodate subsistence-related concerns and spent the bulk of the new subsistence funds on equipment or other priorities. [15] Subsistence funds, moreover, were gradually phased in; the first subsistence coordinators were hired during the summer of 1991, but some hiring and other subsistence-related expenditures did not take place until the following year. By mid-1992, each park had designated an employee to oversee subsistence-related concerns. [16]

A primary aspect of the subsistence coordinators' job was to provide a local contact for the implementation of subsistence policies and regulations. In that capacity, the coordinators organized and helped conduct SRC meetings, approved various subsistence-related permits, and discussed subsistence problems with both park staff and subsistence users. The interpersonal nature of those interactions, and the fact that the agency, at long last, had personnel in place who could focus on subsistence concerns, inevitably meant that the agency's policies could be described and explained more effectively to users than was previously the case. Subsistence users, however, also benefited; NPS representatives, having more time to listen to users, began to more fully understand their lives, their subsistence patterns, and their concerns with federal policies. In a number of cases, subsistence coordinators—several of whom had lived in rural Alaska prior to assuming their jobs—empathized with the users' concerns. They also came to recognize, all too often, that users had legitimate grievances against the agency's interpretation of various subsistence regulations, and as a result, they took an advocacy role with park and regional officials in an attempt to modify the agency's stance. [17] Not surprisingly, NPS employees who were primarily or exclusively involved with subsistence matters were more likely to empathize with the plight of subsistence users than those to whom subsistence duties were a tangential part of their job.

Perhaps the first evidence of this empathy was manifested not long after the first subsistence coordinators began working at the parks. As noted above, several SRCs spent time during 1990 and 1991 mulling over how to react to the Interior Secretary's responses to their initial hunting plan recommendations, and in late 1991, they began sending revised recommendations back to Secretary Lujan. The Wrangell-St. Elias SRC sent him two recommendations in December 1991; its action was followed three months later by a similar letter from the Gates of the Arctic SRC, which made three recommendations. Both of the SRC letters contained at least one recommendation that was similar if not identical to those that had been rejected in 1988.

|

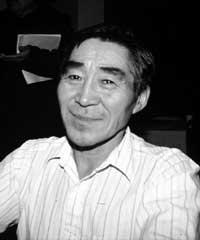

| Roger Siglin, who served as Gates of the Arctic's superintendent from 1986 to 1993, occasionally clashed with regional officials on subsistence-related issues. NPS (AKSO) |

Recognizing that part of the SRCs' ire toward the government was based on its lackadaisical response to their hunting plan recommendation, the Interior Secretary began to formulate a response to both letters soon after they arrived in Washington. Regarding the Wrangell-St. Elias letter, there was apparently little controversy over what the Interior Secretary should say; steering a cautious course, the Secretary's office urged further study for both of the issues that the SRC had raised. [18] But in regard to the Gates of the Arctic SRC's recommendations, a diversity of opinion emerged. In his initial overview of the SRC's letter, park superintendent Roger Siglin unequivocally stated that all three SRC recommendations—related to resident zones, access, and traditional use zones [19] — were "reasonable and within the purview of the commission." Siglin stopped short of wholeheartedly endorsing the three recommendations—he was cautious in his support for the first two and remained neutral on the third—but he did not reject any of them out of hand. [20]

Shortly after he sent the letter, however, several members of the region's Subsistence Division met with park staff in Fairbanks. Siglin, in response, penned a revised letter. He thanked Division personnel for "clarifying the appropriate format, timing, and content for these comments now and in the future;" he did, however, "feel strongly that park staff perspective ... is a necessary element if background is required for Secretarial analysis and response." Siglin reiterated that each of the SRC's recommendations were "reasonable and within the purview of the commission," but perhaps at the region's insistence, numerous clarifying comments were added to each discussion item. [21] The recommendations were then forwarded to Washington, where they were reviewed by Deputy Undersecretary Vernon R. Wiggins and other Interior Department officials. As a result of that review, the Secretary's office stated that the first recommendation was "consistent with Congress' intent to protect opportunities for subsistence users," and it further stated that "the NPS has drafted a proposed regulation" that would have implemented that recommendation. But the Secretary, taking the same protective stance that it had in 1988, rejected the SRC's other two recommendations. "Congress," the letter stated, "intended that NPS management relative to subsistence is to maintain traditional NPS management values," and the Secretary apparently felt that the SRC's two recommendations ran contrary to those "traditional ... values." [22]

During the same period in which the Secretary was considering Gates' SRC recommendations, the region's Subsistence Division staff was producing the first of several subsistence issue papers. By December 1992, two such papers—dealing with ORV/ATV use and the construction of structures in park areas—had been completed in draft form and circulated to the various subsistence superintendents. These thematic papers were an attempt to simplify the complexity of concerns surrounding various subsistence issues; each began with a reiteration of the 1981 regulations and pertinent language from the Congressional Record, to which were added opinions and interpretations previously expressed by Washington-based Interior personnel as well as regional NPS officials. No attempt was made to forge new policy; instead, these papers provided the opportunity to express existing policy in the simplest possible terms. [23]

Gates of the Arctic Superintendent Roger Siglin reacted strongly to both the substance and the implications of the two draft issue papers. In a December 1992 letter to regional Subsistence Division head Lou Waller, Siglin declared that "a piece meal policy-setting approach without the benefits of a coherent regional subsistence policy built on reasoned debate and consensus is premature at this time." He complained that

there is still a general tendency for managers to react to consumptive subsistence activities as an adverse use within these vast park system units. This tendency has been widespread and debilitating with respect to the process of seeking creative management solutions to these critical issues. We have made very little progress [in this area] since the passage of ANILCA.

Siglin also decried the "years of restrained funding" in the subsistence arena, and he vowed that "We must be in this for the long haul and reject simplistic or shortsighted solutions that unnecessarily restrict the options of future managers." Siglin, by this time, knew that regional subsistence head Lou Waller had organized a brief Subsistence Workshop, which was to be held in January 1993. Perhaps in anticipation of that upcoming event, he requested "that superintendents and subsistence managers from the parks have the opportunity to discuss these critical regulatory position statements as well as other concerns as a group." [24]

|

| John M. (Jack) Morehead served as the Regional Director for Alaska's NPS units from 1991 to 1994. NPS (AKSO) |

Other superintendents shared Siglin's concerns. [25] The tone of the various draft issue papers, combined with the Interior Secretary's narrowly-focused response to the Wrangell-St. Elias and Gates of the Arctic recommendations and the restrictive way in which regional subsistence officials were handling the Wrangell-St. Elias resident zone boundary issue, made park personnel feel increasingly empathetic toward subsistence users. Indeed, several superintendents were convinced that if the present regime continued, subsistence activities would begin to decline, and there was a vague perception that, given a continuation of existing policies, subsistence might well be regulated out of the parks. [26] Moreover, a perceived gap between how field personnel and regional personnel were interpreting subsistence regulations suggested that a reassessment of subsistence management policies was in order. Inasmuch as Regional Director John M. Morehead was himself a strong advocate for the rights of subsistence users, he readily agreed to a request from various superintendents that the January subsistence workshop be scuttled in favor of an extended conference that would allow a broad discussion of subsistence matters. As noted in one of Gates of the Arctic SRC's newsletters, the week of March 22-26, 1993 would be spent

thoroughly evaluating the statewide subsistence management program. The Regional Director and staff will meet with Superintendents and staff ... in a variety of sessions designed to identify problem areas within the programs and develop solutions. The Alaska Regional Director will make the final decision regarding the general agency philosophy toward subsistence in the parks, the appropriate balance between field areas and the Anchorage office in staffing and funds, and just how policies will be developed in the future. [27]

The conference, held in Anchorage, took place much as had been planned. [28] A variety of officials—superintendents and subsistence coordinators, regional managers, a Solicitor's Office representative and a cultural resource expert—shared ideas on philosophy, problem areas and possible solutions. As Lake Clark superintendent Ralph Tingey noted, "A major benefit of this conference is that it finally focuses all managers on a single important issue." The tone of the meeting was set by retired NPS historian William E. Brown, who gave the first oration. Many who attended the conference were stirred by both the power of his verbiage and his iconoclasm, and the daring tone he set as the conference's self-described "point man" may well have allowed other attendees to pursue similarly independent policy positions. [29]

One of the most-discussed problem areas was the degree to which parks should be involved in the subsistence decisionmaking process. Siglin, the first superintendent to speak, stated that frustration levels in the parks were high and that parks wanted more of a direct role in the decision making process; Karen Wade, from Wrangell-St. Elias, said that the agency needed a decentralized and localized approach to subsistence management; and Deputy Regional Director Paul Anderson advocated an approach that encouraged greater involvement of front-line employees. Bob Gerhard, from the Northwest Areas Office, also appeared to be arguing for a change in the decision making structure when he posed the rhetorical question, "Is subsistence here to stay or are we going to try to nitpick it apart and have it go away?" But others appeared to disagree with these viewpoints. Marvin Jensen, from Glacier Bay, argued for a more unified approach to subsistence and more teamwork with the regional office, and Joe Fowler from Lake Clark also bemoaned that there was a lack of consistency in how the agency dealt with subsistence. Chris Bockmon, from the Solicitor's office, concluded that the various laws and regulations under which the NPS operated argued for a unified approach to subsistence management. "Management must be more consistent than divergent in approach," he added. Regional subsistence chief Lou Waller, trying to steer a path midway between these viewpoints, said that subsistence management latitude was analogous to a "broad road with white outer markers. It is possible to maneuver within the lines, but we must avoid going over them and totally off the route intended by Congress." ("Management of ... the Alaska national parks," Waller said later, "should not be management by popularity.") Cary Brown, from Yukon-Charley Rivers, also appeared to espouse portions of both viewpoints when he averred that the agency needed a "system that allowed for local determinations with consistency between parks." [30]

Beyond that central question, participants presented a broad array of subsistence-related problems. One of the few commonly-held problem areas lay in education and training; several NPS field personnel readily admitted their ignorance regarding subsistence matters, and in addition, field staff repeatedly mentioned that SRC members needed periodic training. Finally, those who were involved in subsistence admitted to a general lack of direction; in order to gain a renewed orientation, therefore, the assembled participants completed a draft policy statement for the regional subsistence program. For the next four years, that draft document remained the region's best statement of subsistence policy direction. [31]

Perhaps because the conference was the first time in which such a diversity of decision-makers had met on the topic, few new policy directions were established. [32] Even so, the conference was widely perceived as being successful. At a mid-April meeting of the Gates of the Arctic SRC, for example, Superintendent Siglin felt that

changes will be seen as a result of that conference. One is that subsistence is a legitimate use of park resources, strongly endorsed by Morehead. Also he expects stronger general support for SRCs. ... SRC members [however] must also respect the constraints that laws put on subsistence users, seek ways to minimize conflicts between wilderness and subsistence users, and support sound wildlife practices. [33]

One organizational change that resulted from the March 1993 conference was the establishment of an ad hoc Superintendents' Subsistence Committee. By June 1993, this group had already held two teleconferences, and briefing papers had been completed on several of the major topics that had been addressed at the conference. In addition to completing the remainder of the briefing papers, two goals that the ad hoc committee hoped to pursue were the establishment of an annual meeting of the various SRC chairs and further training for rank-and-file SRC members. [34]

|

| Regional NPS officials in 1993 included (top row, left to right): Clay Alderson (KLGO), Bill Welch (ARO), Steve Martin (GAAR), Bob Gerhard (NWAK). Second row: Mickie Hellickson (SITK), Karen Wade (WRST), Anne Castellina (KEFJ), Dave Ames (ARO). Third row: Jack Morehead (ARO), Paul Haertel (ARO), Judy Gottlieb (ARO), Don Chase (BELA). Fourth row: Paul Anderson (ARO), Janet McCabe (ARO), Russell Berry (DENA), Marvin Jensen (GLBA), Will Tipton (KATM). Front row: Ralph Tingey (ARO), Paul Guraedy (YUCH). NPS (AKSO) |

During the summer of 1993, however, the momentum that had been established in the wake of the subsistence conference apparently dissipated. [35] Perhaps because of the July 1993 retirement of Roger Siglin, who had played a crucial role in organizing the subsistence conference, no further meetings of the Superintendents' Subsistence Committee took place.

In many respects, it appeared that the subsistence conference, at best, had had a temporary impact on long-established decision making patterns. Despite the urgings of two SRCs as well as the Superintendents' Subsistence Committee, the agency made no move during the summer or fall of 1993 to convene a meeting of the SRC chairs; similarly, nothing was done regarding training for SRC members. And subsistence users continued to be vexed by departmental inaction on several key SRC resolutions; in one particularly flagrant case, a resolution put forth by the Lake Clark SRC calling for so-called roster regulations, foot-dragging at the Secretarial level was such that the SRC was forced to send a reminder note to the Interior Secretary asking for a response. That letter, sent in August 1992—more than six years after the SRC had sent its resolution—brought forth only a lukewarm response from the NPS's Washington office. No one appeared willing or able to break the bureaucratic logjam. By the fall of 1993, these and similar actions (or inactions) were causing park superintendents to again voice the same complaints that had been heard prior to the March conference. Many of those complaints were directed at the Subsistence Division's chief who, in the opinion of many superintendents, refused to consult or coordinate with them on various subsistence proposals and activities. [36]

C. Agency Program Modifications, 1993-1996

|

| Bob Gerhard, who served as the superintendent for the Northwest Alaska Areas from 1992 to 1996, has been involved with subsistence issues in Alaska since the 1970s. He currently serves as a program manager in the regional office. NPS (AKSO) |

Regardless of the success or failure of the March 1993 conference, the issues that had been raised there refused to go away; and before long, conflict arose once again between park and regional officials. The next area of contention took place in the Northwest Alaska Areas Office as a result of nearly-identical hunting plans that the Cape Krusenstern and Kobuk Valley SRCs had forwarded to the Interior Secretary. (This plan included six thematic areas; the first such area included a critical recommendation calling for a huge resident zone to include all residents within the NANA Regional Corporation boundaries, while other recommendations dealt with aircraft and ATV access, traditional use areas, and sundry topics. (Portions of the plan, as noted in Chapter 6 as well as in Section A [above], had been finalized back in the mid-1980s but had never been sent to Washington.) These resolutions were finally mailed to Secretary Babbitt shortly after an August 1993 joint SRC meeting.

Superintendent Bob Gerhard, hoping to influence the agency's actions or at least hoping to crystallize agency opinions, sent Regional Subsistence Chief Lou Waller what was admittedly a "very rough draft" of a response letter in October 1993. In that letter, he noted that the SRCs' proposed resident-zone idea was "generally within the guidelines stated in ANILCA §808, and to be consistent with the intent of the legislation," and regarding other SRC recommendations, Gerhard appeared eager to be as amenable as the laws and regulations allowed.

The regional office responded by meeting with park staff in mid-November; then, three weeks later, it penned its own response letter which dealt less liberally with the SRCs' recommendations. Park staff, who had been promised that they would be immediately apprised of all regional-office actions in the matter, had to wait more than two weeks before hearing about the region's draft letter. Gerhard, clearly taken aback by the turn of events, told regional officials that "if we are supposed to be working together on this project, I do not think we are doing it well." [37] He made a renewed attempt to ink a mutually-acceptable draft response letter, but as the files on this subject clearly indicate, park and regional officials were unable to forge a final response letter. Finally, in June 1994, the two SRCs signaled that their patience had worn thin. In identical letters written to Interior Secretary Babbitt, Cape Krusenstern SRC chair Pete Schaeffer and Kobuk Valley SRC chair Walter Sampson let it be known that because "we have not received a response to our recommendations ... further meetings of the Commission will be contingent upon the receipt of a formal response to the recommendations contained in the proposed hunting plan." [38]

|

| Ralph Tingey, the superintendent for Lake Clark National Park and Preserve from 1992 to 1996, was a key member of a 1994 task force that produced a draft review of subsistence laws and agency regulations. Ralph Tingey photo |

|

| Jon Jarvis, who was Wrangell-St. Elias's superintendent from 1994 to 1999, was the principal author of a report that reviewed of the region's natural resources program. One outcome of that report was the dissolution of the region's subsistence division. NPS (AKSO) |

By this time, new pressures were beginning to confront the Park Service. Beginning in late 1993, Clinton administration officials let it be known that the NPS, along with other government agencies, would be facing likely budget cutbacks and a staff reorganization. The NPS, in response, recognized the necessity of moving many personnel to the parks from central and regional office positions. But regional officials were also aware that reorganization methods that might work at other regional offices would hold little relevance in Alaska, where subsistence management was a major agency function. And as suggested above, it was becoming increasingly obvious that the subsistence problems that had brought about the Spring 1993 superintendents' conference had not been solved, and there was almost a complete breakdown in communications between regional subsistence officials and several park superintendents. In the spring of 1994, therefore, Regional Director John M. Morehead (in the words of one subsistence expert) "threw up his hands" over the continuing difficulties between the regional office and the field and demanded that the major subsistence problems be re-analyzed by establishing a regional subsistence working group or task force. As Gates of the Arctic Superintendent Steve Martin explained, "the task force was a working group of NPS managers [intended] to assess the subsistence management program and identify issues requiring policy development." The group, which was asked to look "at subsistence issues on a regional basis," was selected by Deputy Director Paul Anderson and Management Assistant William Welch; it consisted of superintendents Ralph Tingey and Steve Martin along with subsistence specialists Lou Waller, Hollis Twitchell, and Jay Wells. Others attended meetings and contributed to the discussion from time to time. [39]

The task force, which met for the first time on May 12, quickly recognized that its primary task would be the compilation of a subsistence issues paper that would clearly and explicitly describe the major subsistence management issues. It may be recalled that the regional subsistence division, back in late 1992, had written a few draft position papers on specific thematic topics, but the 1994 task force wanted consistency in how a wide variety of subsistence laws and regulations was being interpreted. The task force, therefore, undertook a comprehensive review of laws and regulations that affected Alaskan subsistence activities. It met some twenty times over the next several months (primarily but not exclusively in Anchorage), and by the fall of 1994 it had completed a "Draft Review of Subsistence Laws and National Park Service Regulations." The group felt that it had broken much new ground during the discussions that resulted in that document; at the same time, however, members felt that there was little need to distribute the document to anyone outside of the agency. As a result, only a few copies of the draft document were produced, and for more than a year the document was largely ignored. [40]

During 1994 and 1995, the specific direction in which the agency's reorganization was to take place became increasingly clear. Former regional offices, for example, were cleaved into either field offices or system support offices, and funding allocation authority was significantly shifted from the old regional offices to the newly-formed Alaska Cluster of Superintendents. Months after implementing that change, however, it became increasingly obvious to officials at the park level that the call for reorganization as detailed in the NPS Restructuring Plan—particularly as it related to natural resource management—had not yet been implemented at the regional level; in addition, the new balance of power between the regional office and the parks (from "directing" the parks to providing "support" to them) was not being applied in Alaska. To overcome these structural problems, Field Director Robert Barbee in early December 1995 organized a four-person team, headed by Wrangell-St. Elias superintendent Jon Jarvis, to analyze the problem and recommend workable solutions. [41]

The team soon ascertained that the existing natural resource management system (consisting of the Subsistence, Natural Resources, Minerals Management and Environmental Quality divisions) was an inefficient organizational breakdown. Rather than subdividing tasks by program or issue, it argued, tasks should instead be based upon discipline or function. It thus recommended that natural resource programs be undertaken by four new divisions (or "teams"), plus one existing division that would assume a new function. The plan called for seven of the nine staff members who then comprised the Subsistence Division to be included in either the Biological Resources or Program Support Teams, both of which were new; the remaining two staffers would be added to the long-established Cultural Resource Division. The plan, to a large extent, was worked out in a series of meetings in mid-February 1996. Agency leadership broadly approved the plan during the last of those meetings, and a report delineating the reorganization process—dubbed the "Jarvis report"—was prepared soon afterward. [42] By May of 1996 the Subsistence Division ceased to exist; most of its former functions were assumed by interdisciplinary teams of new and old staff and by other members of the natural resource and cultural resource teams. [43] Paul Anderson, who had assumed leadership of the NPS's subsistence program in late 1994, continued to guide the agency's subsistence efforts during this transition period; key to his management style was the promotion of a more consultative and participatory approach to addressing and resolving subsistence issues.

D. The NPS Subsistence Program, 1996-present

|

| Paul Anderson served as the Alaska Region's Deputy Superintendent from 1992 to 2002. From 1994 to 1999, he served as the NPS's representative to the Federal Subsistence Board. NPS (AKSO) |

No sooner had the mid-February meetings taken place than SRC members and other observers began to recognize, to an ever-increasing degree, that NPS staff bore a new attitude toward subsistence issues. (Superintendent Jarvis himself called it a "new paradigm.") Personnel at both the support office as well as the various parks listened anew to subsistence users' concerns, and agency personnel made renewed attempts to solve long-simmering issues related to eligibility, access, and similar topics. And as if to underscore the agency's willingness to sound out subsistence users' concerns, Deputy Regional Director Paul Anderson invited the various SRC chairs to an Anchorage workshop on June 1, 1996. It was the first time that the chairs had met in more than six years; furthermore, the NPS noted that "the meeting was a very positive and productive session and several recommendations resulted." [44]

Even before reorganization was complete, several subsistence experts felt that one significant way the agency could display a new openness toward subsistence issues was by preparing a public document explaining its stance on eligibility, access, and similar matters. As noted above, the NPS had expended a great effort two years earlier in order to prepare a "Draft Review of Subsistence Law and National Park Service Regulations," and shortly after Alaska's NPS superintendents met in mid-October 1995, agency officials decided that this document should be dusted off and used as the basis for public comment. [45] Over the next few months, members of all of the active SRCs were given a copy of the document and asked to comment on it. Copies were also distributed to state officials, regional advisory councils, representatives of Native corporations and conservation groups, post office boxholders in resident zone communities, and others interested in subsistence activities on NPS lands. [46] Bob Gerhard, an ad hoc subsistence coordinator in the regional office, played the lead role in distributing the document and receiving comments related to its strengths and weaknesses.

NPS subsistence staff, after receiving a broad array of comments, held a subsistence workshop in Anchorage on April 14-15, 1997 and hammered out a final draft, which was issued that July. This paper was critiqued once again, and a final copy was completed and distributed a month later. Despite the "final" nature of the August 1997 paper, those who coordinated its completion were careful to note that "the document is living and will continue to evolve." As if to emphasize the open process that produced the paper, each section of it included not only the final text but all comments to the draft and the NPS's response to those comments. Just a week after it was completed, the issues paper was distributed to an assembled meeting of SRC chairs; soon afterward, it was mailed out to local fish and game advisory committees, Native organizations, federal and state agencies, conservation groups, and interested individuals. The NPS produced and distributed more than 250 copies of the issues paper to a broad array of interested individuals: federal and state legislators, SRC members, and other subsistence users as well as to NPS staff. [47]

A project far more massive, and no less important to the various SRCs, was the preparation of a series of subsistence management plans. As has been noted above, Title VIII of ANILCA gave few specifics as to what specifically constituted a "program for subsistence hunting" in the various park units, and because of that lack, the SRCs provided widely varying versions of what, in their opinion, fulfilled that requirement. The NPS, as a result, occasionally fumed that what the SRCs submitted fell short of a "program for subsistence hunting," and although various general management plans called for the preparation of a subsistence management plan, agency officials were loathe to make specific suggestions for what specifically was needed.

Shortly after the reorganization was completed, Superintendent Jarvis suggested that what constituted a "subsistence management plan" was, to a large degree, a compendium of all subsistence-related actions—Congressional laws, departmental regulations, agency interpretations and SRC recommendations—pertaining to a particular park unit. Given that administrative road map, he asked if subsistence specialist Janis Meldrum would be able to work together with Jay Wells, his chief ranger and subsistence coordinator, to assemble such a record for Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. Work began in the spring of 1996, and by February 1997 Meldrum had an initial draft ready for distribution to the park's SRC members. For the next two years, the park's SRC reviewed and critiqued the plan at its semiannual meetings; in response to members' comments, Meldrum revised and expanded the draft plan. Finally, in November 1998, the public review process had been completed, and Meldrum and the SRC declared that a mutually satisfactory product was at hand. [48]

|

| The Denali National Park Subsistence Resource Commission has had the same chairperson—Florence Collins of Lake Minchumina—since its inception in 1984. Since 1993, communications from Denali's SRC have sported this handsome letterhead. NPS (DENA) |

Meldrum has also compiled two other subsistence management plans. In the spring of 1997, she began work on the Denali National Park SMP and was able to complete an initial draft plan in time for the SRC's July 1997 meeting; the plan, however, did not go through its ninety-day public review period until the fall of 1999, and the SRC did not officially approve it until August 2000. And in the fall of 1997, she began work on a similar effort for Lake Clark National Park. She distributed an initial draft of the volume at the park SRC's February 1998 meeting, and after a ninety-day public review period, the Lake Clark SRC declared the plan complete at its October 2000 meeting. [49]

Two other subsistence management plans were guided, to some extent, by the efforts of subsistence specialist Clarence Summers. In mid-1997, Summers assisted Steve Ulvi on a plan for Gates of the Arctic National Park, and during the same period he started work with Susan Savage (and later with Donald Mike) on a similar volume for Aniakchak National Monument. The Gates of the Arctic volume was initially shown to park's SRC in January 1998, but a draft of the Aniakchak volume was not ready until its SRC met in November 2000. The Gates of the Arctic SRC, along with Superintendent Dave Mills, declared that its subsistence management plan was complete at the November 14, 2000 SRC meeting; as for Aniakchak, the monument's SRC approved its hunting plan at a Chignik Lake meeting on February 20, 2002. [50]

The success of the various subsistence management plans has spawned similar educational efforts at various park units. The goal of some of these efforts has been to educate subsistence users about basic hunting rules and regulations, while other efforts have attempted to educate the general public about subsistence activities and their role in Alaska's national park units.

The first such effort, begun in February 1998 at the request of the Denali National Park SRC, was the preparation of a users' guide that would give condensed, pertinent information about subsistence rules and regulations as they pertained to Denali-area subsistence users. This short report was first presented to the SRC at its August 1998 meeting; the SRC approved a final version six months later, and in August 1999 copies were mailed to all postal boxholders in Denali's four resident zone communities.

Soon after work began on the Denali report, park and support-office staff began work on a similar effort at Wrangell-St. Elias. But based on suggestions from the park's SRC, the agency decided, in lieu of a users' guide, to compile a series of public-education hunting maps and a brochure briefly describing the park's subsistence program to area subsistence users. By early May 1998, the NPS had produced maps for the Northway and Tanacross areas for caribou, for sheep, and for moose. The maps were well received by the residents of those communities. By the following March, copies of the final brochure had been mailed out to all boxholders in the park's 18 resident-zone communities, and two months later, a new set of hunting maps (for sheep, caribou, and moose) was made available to residents of twelve area communities.

At other park units, SRCs have suggested new ways to publicize the agency's subsistence program. In the fall of 1998, work began on a Lake Clark National Park users' guide, and two years later a similar effort began at Gates of the Arctic National Park. The Lake Clark guide was completed in March 2001, while the Gates of the Arctic guide has been finished in draft form. At Denali National Park and Preserve, the SRC opted for a subsistence brochure; unlike its equivalent at Wrangell-St. Elias, this was intended primarily for park visitors rather than area subsistence users. Alaska Support Office staff completed this task in early 2001. [51]

In the years since the issuance of the so-called "Jarvis report," relations between NPS staff and subsistence users have been fairly amicable. This "era of good feeling"—which was a decided change from the storminess that had characterized relations in past years—has emerged for several reasons. First, both park staff and support-office (regional) staff came to recognize both the necessity and desirability of finding common solutions to subsistence-related problems. And as a corollary to that mutual recognition, the agency has been able to provide sufficient staff time and financial support to allow SRC members and other subsistence users to periodically and democratically express their opinions on subsistence-related issues.

Communication has been a key to this "new paradigm." The agency, for example, has encouraged each of the SRCs to meet as often as necessary and has consistently provided funding for travel and per diem expenses, even when meeting in remote, rural locations. In addition, the agency has arranged for annual opportunities for the SRC chairs to meet, discuss common problems, and formulate resolutions of mutual interest. [52] The SRCs, with the agency's blessing, have made recommendations on a wide variety of topics in recent years, and their advice is now sought by the various regional advisory committees on matters pertaining to wildlife and fisheries management within the areas of their jurisdiction. In recognition of that expanded role, the SRCs now often schedule their meetings so that they can take maximum advantage of either 1) submitting new wildlife and fish proposals so they can be considered by a regional advisory committee, or 2) evaluating previously-submitted proposals that affect wildlife and fish populations within a given park unit.

|

| Since 1996, the various SRC chairs have met each year to discuss common issues and concerns, both with each other and with NPS officials. Photographed at their October 2001 meeting, chairs included (left to right): Pete Schaeffer (CAKR), Ray Sensmeier (WRST), Florence Collins (DENA), Jack Reakoff (GAAR vice-chair), and Walter Sampson (KOVA). Author's collection |

Managing Alaskan subsistence resources in recent years has been a more decentralized process than had been the case prior to the Subsistence Division's dissolution. The so-called Jarvis report had suggested one possible management solution—in lieu of a formalized divisional structure, "interdisciplinary teams (IDTs) would be formed to handle existing and new issues ... each IDT would be ... temporary or long term as the project dictated." Indeed, an ad hoc IDT structure was employed during much of 1996 and 1997 (i.e., during the completion of the issues paper) to accomplish subsistence-related goals; the only formal structure was that provided by a so-called Subsistence Committee of the Alaska Cluster of Superintendents. [53] But as the issues paper neared its completion, subsistence personnel began to recognize the need for some form of regularized organization. In order to provide a periodic forum for the discussion of common subsistence issues, Bob Gerhard—who had been serving as an ad hoc subsistence facilitator since his return to Anchorage in September 1996—convened a monthly teleconference beginning in June 1997. [54] This meeting, which provided the opportunity for park subsistence coordinators, superintendents, regional managers and regional subsistence staff to share ideas and opinions, met each month on a fairly regular basis.

The latest change to the subsistence management structure took place in 1999. In mid-February of that year, the various park subsistence coordinators, along with other subsistence experts, convened for several days in Anchorage and established a regional Subsistence Advisory Committee. By forming such a committee, subsistence personnel were provided a designated conduit for evaluating subsistence projects; as such, it put them on a par with their co-workers in the natural resource and cultural resource spheres. [55] Several months later, the Alaska Cluster of Superintendents approved the petition that officially sanctioned the committee. Ever since that time, subsistence personnel have continued to meet once each month; meetings of the Subsistence Advisory Committee have alternated with meetings of the more loosely-affiliated group that had been meeting since June 1997. Another managerial change in 1999 was a direct outgrowth of the assumption of fisheries management on federal lands, which took place on October 1 (see Chapter 9). In recognition of that action, Sandy Rabinowitch became the de facto coordinator of wildlife-related subsistence activities—particularly as they related to the Federal Subsistence Board—while Bob Gerhard assumed a coordinating role over the agency's subsistence fisheries management efforts.

E. Subsistence in the Legislature, Part I: the Case of Glacier Bay

One of the most contentious subsistence-related issues that the NPS dealt with during the 1990s concerned subsistence harvesting in Glacier Bay and in adjacent waters within Glacier Bay National Park. As noted in Chapter 6, provisions within ANILCA had made it clear that subsistence uses in these areas were prohibited. The State of Alaska, however, had kept the issue alive, and owing in part to actions by Fish and Game Commissioner Don Collinsworth, the NPS and Hoonah residents narrowly avoided a confrontation over the issue during the summer of 1989.

That fall, many Hoonah residents renewed their intention to press for subsistence access to Glacier Bay, and before long, the NPS and the ADF&G were once again at loggerheads. Commissioner Collinsworth, as he had in 1989, moved to issue subsistence permits for Glacier Bay; and the state legislature, in a similar vein, passed a resolution asking that the NPS "amend its regulations in order to ... expressly provide for subsistence uses in the Park." The NPS, in response, told state authorities that the agency had "no administrative authority for allowing subsistence activities in the park." Having few other alternatives, it tried to dampen what had become a high-profile issue and announced that it would be "lenient in its enforcement" of the subsistence regulation. The agency encountered few enforcement problems that summer. [56]

By this time, authorities on both sides of the issue recognized that the only way to change the existing state of affairs—that is, the only way for local residents to gain legal, long-term subsistence access into Glacier Bay—lay in the passage of federal legislation. [57] Alaska's Congressional delegation took no immediate action in the matter. But in August 1990, the Alaska Wildlife Alliance filed suit against the NPS in the Anchorage District Court, claiming that the agency, among other things, was allowing illegal commercial and subsistence fishing to occur. A month earlier, on July 1, the NPS—perhaps knowing of the imminent AWA suit—made it known that it intended to issue a proposed rule regarding commercial fishing in the bay; that rule would state that commercial fishing in the bay's few wilderness waters would be immediately prohibited and that commercial fishing in the remainder of the bay be prohibited after December 1997. (Subsistence was not addressed in the proposed rule.) The Congressional delegation stridently opposed this proposed rule, which was issued on August 5, 1991. [58]

|

| Marvin Jensen served as the superintendent of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve from 1988 to 1995. Fishing issues, both commercial and subsistence, remained controversial throughout this period. NPS (AKSO) |

Anticipating that rule, both Senator Frank Murkowski and Representative Don Young introduced bills that summer that would authorize both commercial fishing and subsistence uses in Glacier Bay. (One other provision in these bills was related to cruise ship entry.) In September and October, the NPS held hearings on the proposed commercial fishing regulations in eight Alaskan communities as well as in Seattle. The following May, Murkowski's and Young's bills were addressed by their respective subcommittees; they were passed by voice votes in June and advanced to the full committee. In October 1992, however, the bill collapsed in the Senate during the waning hours of the 102nd Congress. [59] The status quo remained, at least for the time being. Although similar bills would be resurrected in the 103rd Congress, they would be no more successful than their predecessors. [60]

During the fall of 1992, in the midst of last-minute negotiations over Senator Murkowski's Glacier Bay bill, an incident took place in the bay that started a whole new round of controversy related to subsistence fishing's legal status. On October 6, NPS rangers observed Gregory Brown, a Tlingit residing in Hoonah, hauling a dead hair seal from a skiff to a seine boat. Inasmuch as the action took place near Garforth Island, which is located near Adams Inlet within the bay, the rangers cited Brown for violating the prohibition against subsistence harvesting. Brown readily admitted that he had killed the seal; it was needed, he claimed, for a "payback party" (a kind of potlatch) for a recently deceased relative. Given these circumstances, Brown's citation aroused strong feelings in Hoonah. The Huna Traditional Tribal Council soon sent a letter of protest to Alaska's Congressional delegation; it charged that "we are made criminals for our food" and reiterated longstanding concerns that the NPS was insensitive to the Hoonah's cultural and historical ties to Glacier Bay. [61]

Those who defended Brown checked the various federal regulations that pertained to the NPS's management of the park's marine waters. They evidently discovered that a 1987 technical amendment to the agency's 1983 regulations meant that the regulations specifically applied to privately owned lands but that it was "silent as to the applicability" of the regulations on other "non-federally owned lands and waters" within the boundaries of park areas. Therefore, the regulations as they existed in 1992 "had the unforseen and unintended affect [sic] of rendering ambiguous the applicability of NPS regulations to navigable waters in Glacier Bay National Park." Because the NPS did not have clear regulatory authority over the navigable waters of several NPS units—of which Glacier Bay was just one example—the Interior Department moved to dismiss the case in December 1993. [62]

The loss of this case, of course, meant that the NPS had no clear authority to enforce a broad range of regulations pertaining to Glacier Bay's marine waters. In order to reassert that authority, Russel Wilson of the NPS's Alaska Regional Office was asked to draft an interim rule that established the federal government's clear regulatory authority without addressing the larger question of who owned the park's submerged lands. This rule, which was promulgated "to insure the continued protection of park wildlife ... and to clearly inform the public that hunting continues to be prohibited," was published in the Federal Register on March 29, 1994; it became effective the same day and was to remain valid until January 1, 1996. The public was given ninety days—until June 27, 1994—to comment on the interim rule. After receiving and considering those comments, the NPS published a Proposed Rule, which was broadly applicable to units throughout the National Park System, in December 1995. [63] The rule called for another round of public comments, to end in February 1996, and during that period both the Alaska Attorney General and the state legislature (among other entities) submitted comments. Five months later, the NPS issued a final rule on the subject. The NPS, with this rule, thus regained the legal ability to enforce subsistence (and other) regulations on Glacier Bay's waters while sidestepping the complicated issue of submerged lands ownership. [64]

Meanwhile, NPS officials moved to curtail commercial fishing within the bay. As noted earlier in this chapter, activities during the early 1990s had led to a standoff; the NPS—faced with a wall of protest at a series of public meetings—had been unsuccessful in promulgating a commercial fishing ban in Glacier Bay National Park, but Alaska's congressional delegation had likewise been unsuccessful in two successive Congresses in implementing a bill that would have allowed subsistence fishing and mandated the continuation of commercial fishing. A small part of that standoff was resolved in conservationists' favor in 1994, when District Judge H. Russel Holland ruled, in Alaska Wildlife Alliance's lawsuit against the NPS, that commercial fishing was prohibited in the park's wilderness waters. Three years later, this decision was upheld in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. In other matters related to Glacier Bay fishing, however, the standoff continued. What eventually emerged from this standoff was a series of informal workshops among the major stakeholders—Interior Department officials, commercial fishermen, area residents, and others, collectively known as the cultural fishing working group—that made major strides in resolving outstanding issues. These meetings continued until the winter of 1997-98. [65]

|

| Frank Murkowski has been Alaska's junior U.S. Senator from 1981 to the present time. He introduced bills in 1991, 1993, 1997, and 1999 that would have legitimized or expanded fishing rights in Glacier Bay. Office of Sen. Murkowski |

In April 1997, NPS officials decided that they would once again issue a proposed rule that called for a termination of commercial fishing in Glacier Bay. The rule was similar to that proposed in August 1991, but it called for a 15-year rather than a 7-year phaseout period. The NPS's action, predictably, resulted in Senator Murkowski submitting a section into a larger bill (authorizing ANILCA amendments) that would have legalized both subsistence and commercial fishing in the bay. This bill was similar to bills that the Senator had submitted in both 1991 and 1993. [66] During the next several months, NPS staff began preparing an environmental assessment related to its proposed rule, and the agency held several public hearings in area communities as part of that effort. The NPS issued a final report on that topic in April 1998.

Before the NPS could issue a final rule, however, Senator Stevens was successful in implementing a compromise between the NPS's and Murkowski's position. In the waning hours of the 105th Congress, Stevens inserted a clause (Section 123) into the huge Omnibus Consolidated and Emergency Supplemental Act for Fiscal Year 1999 (P.L. 105-277), which was signed by President Clinton on October 21, 1998. Stevens's compromise allowed commercial fishing to continue unimpeded outside of Glacier Bay proper; within the bay, it delineated zones where commercial fishing would be prohibited. (The section made no mention of subsistence issues.) [67] Senator Murkowski and Representative Young reacted to the compromise by introducing legislation on March 2, 1999 that would have allowed commercial fishing to continue. (That bill remained alive for most of that session before stalling.) Senator Stevens, however, was more successful. In May 1999, Stevens was able to insert a paragraph (Section 501) in the 1999 Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act (P.L. 106-31) that provided a $23 million compensation package for commercial fishers who were impacted by the closures outlined in the October 1998 bill. Given those mandates, NPS officials began enforcing these closures in non-wilderness waters on June 15, 1999. (Enforcement of closures in wilderness waters had begun four months earlier.) [68] In the light of the two recent congressional measures, the agency re-issued a proposed rule on August 2. The new proposal proved uncontroversial, and a final rule on the subject was issued on October 20. [69]

Although Alaska's Congressional delegation was unable to overturn the ban on subsistence uses in Glacier Bay, park officials became increasingly sensitive to local concerns (some of which related to subsistence issues) and began meeting with local residents on items of mutual interest. A major outcome of a series of meetings with Hoonah residents was a Memorandum of Understanding, signed on September 30, 1995 and effective for five years, between Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve and the Hoonah Indian Association. The MOU had several objectives: "to formally recognize our government-to-government relations and recognize areas of mutual concern and support, establish a framework for cooperative relationships, and promote communication between both parties." Since that time the Hoonahs have discussed with NPS officials a number of subsistence-related concerns—a cultural fishery program, the gathering of berries and gull eggs, and other matters—which the agency has attempted to accommodate whenever possible. [70] The MOU was updated for an additional five years on September 29, 2000.

F. Subsistence in the Legislature, Part II: Gates of the Arctic ATV Use

Another contentious subsistence-related issue during this period dealt with the all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) in Gates of the Arctic National Park. As Chapter 6 has noted, the NPS determined during the early 1980s that ATVs were not a traditional means of access in the park; then, in January 1986, the NPS issued a memorandum stating that Anaktuvuk Pass residents' use of ATVs was nontraditional. But NPS officials, recognizing that the amount of ATV-accessible land was insufficient to support villagers' needs, had begun talks back in 1984 to resolve the situation, and in March 1986 the park's Subsistence Resource Commission passed a resolution supporting the concept of a three-way land exchange between the NPS, the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation (ASRC) and the Nunamiut Corporation. Work on an exchange agreement was finalized on January 20, 1989, when the NPS, ASRC, Nunamiut Corporation and the City of Anaktuvuk Pass signed a draft agreement. Among its other provisions, the agreement would have designated several thousand acres as wilderness (of both existing parkland and Native lands transferred to the federal government), and deauthorized wilderness on several thousand additional acres. [71] All parties knew that only Congress could approve these actions, so a team of 11 NPS officials set to work on a legislative environmental impact statement (LEIS) that would provide a factual basis for the proposed land transfers. In the meantime, all parties recognized that until a bill passed Congress, ATV use on park lands was technically illegal. To circumvent that technicality, and to serve the greater interest of a negotiated settlement, NPS officials granted a series of one-year extensions to the 1986-88 ATV impact study, because only under the guise of that study could park ATV use legally continue in areas where a historical pattern had been established. [72]

Work on the document consumed far longer than anyone expected; at least five working drafts were prepared. [73] A final version of the draft LEIS was issued in January 1991. It offered three alternatives, the first of which called for a continuation of the status quo. A second alternative, which combined a negotiated agreement with proposed legislation, was the NPS's proposed action. And a third alternative called for all elements of the second alternative plus a land transfer from the NPS to the ASRC; some 28,115 acres of NPS wilderness land northwest of Anaktuvuk Pass would be transferred to the ASRC, while a 38,840-acre parcel northeast of the village would be transferred from the ASRC and the Nunamiut Corporation to the NPS. This latter parcel would become designated wilderness land.

The second alternative—the NPS's proposed action—stated that 17,825 acres within Gates of the Arctic National Park would be designated as wilderness and would thus be prohibited to ATV use. It also called for the deauthorization of wilderness on 73,880 acres in the park, plus the allowance of dispersed ATV use for subsistence purposes on 83,441 acres of park nonwilderness. (Within the latter category, a network of designated ATV easements had existed since the 1983 Chandler Lake Exchange Agreement—in which ASRC had transferred key Native lands within the park to the federal government—but area residents soon found that access to caribou often took them well away from those easements.) As stated in the draft LEIS, the proposal was intended to "foster a more reasonable relationship between NPS, recreational users and the village residents and provide better public access across Native land to park land." [74]

During March 1991, the NPS held public hearings on the draft LEIS in Anchorage and Fairbanks as well as in Anaktuvuk Pass. [75] As a result of those meetings, the agency received six written replies plus additional oral input. It then commenced preparing its final LEIS, which was completed in February 1992 and issued two months later. In a surprising move, the agency adopted its third alternative—not the second alternative, which had been championed a year earlier. Due to slight variations in acreage calculation from the previous year's document, the NPS agreed to allow 73,992 acres of Gates of the Arctic National Park wilderness to be transferred to less restrictive uses: 46,231 acres would allow for dispersed ATV use, while another 27,762 acres would be transferred from NPS to ASRC ownership. In addition, the deal called for 17,985 acres of park land to be designated as new wilderness, and another 80,401 acres of nonwilderness park land to be opened to dispersed ATV use, and another 2,880 acres of nonwilderness park land to be transferred to Native ownership. A final aspect of the deal, as noted above, was that the ownership of a 38,840-acre parcel northeast of Anaktuvuk Pass would be transferred from Native corporations to the NPS; all of that acreage, moreover, would be designated wilderness. [76] On October 20, 1992, an Interior Department official issued a Record of Decision in favor of implementing the third alternative; that decision was then forwarded to the other three governments for their signature.

The NPS, it should be noted, was careful in its Anaktuvuk Pass-area negotiations to sidestep the larger question of whether ATVs were a traditional means of access in Alaska's national park units. As the Record of Decision noted, the agency still did "not consider ATVs a traditional means of access for subsistence use in Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve and prohibits their use on NPS land. The Native community of Anaktuvuk Pass contends, however, that ATVs have been traditionally used and are necessary to reach subsistence resources in the summer. ... The proposed agreement and legislation meet the objective of resolving the ATV controversy. ... The agreement will also avoid a legal battle over the meaning of the legislative phrase '...other means of surface transportation traditionally employed...' and the NPS position that ATVs are not a traditional means of surface transportation." [77]

The last of the four participants in the Anaktuvuk Pass-area land exchange signed the agreement on December 17, 1992. [78] Revised agreements were signed in both 1993 and 1994, and in June 1994 the administration finally submitted the proposal to Congress. A month later, on July 13, bills intended to implement the agreement were introduced. Two different bills were submitted in the U.S. House of Representatives that day: H.R. 4746, introduced by Rep. George Miller (D-Calif.) by request, and H.R. 4754, by Alaska Representative Don Young. [79] A third bill, S. 2303, was introduced a week later by Alaska Senator Frank Murkowski. The three bills, all called the "Anaktuvuk Pass Land Exchange and Wilderness Redesignation Act of 1994," were identical in asking for an additional 56,825 acres of park wilderness and the dedesignation of 73,993 acres of park wilderness. Where they differed, however, was whether new wilderness acreage was contemplated elsewhere. Miller's bill, which was backed by environmental interests, called for an additional 41,000 acres of Bureau of Land Management wilderness in the Nigu River valley adjacent to Noatak National Preserve, while Young's and Murkowski's bills made no such provision.

On September 21, the major players in this issue—George Miller, Bruce Vento (D-Minn.), and Don Young—brokered a deal and agreed to settle the differences in acreage, and on September 27 the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee issued a report on S. 2303 that called for an additional 17,168 acres of wilderness in the Nigu River Valley. (This figure was chosen so that the bill would result in no net change in wilderness acreage.) This acreage was also incorporated into H.R. 4746. During the closing weeks of the 103rd Congress, many additional NPS-related provisions were added onto H.R. 4746, so when the bill passed the House of Representatives on October 3, the various provisions related to Gates of the Arctic National Park were just one section of a much larger omnibus bill. H.R. 4746 was forwarded on to the Senate, which received the bill on October 8; the Senate, however, was unable to pass a bill containing an Anaktuvuk Pass land exchange during the waning hours of the 103rd Congress. [80]

A bill to implement the deal was quickly re-introduced in January 1995, and because it was fairly noncontroversial, it moved fairly quickly. H.R. 400, introduced on January 4 and calling for 17,168 acres of new wilderness acreage in the Upper Nigu River to be added to Noatak National Preserve, sailed through the House Resources Committee on January 18, and on February 1 the bill passed the full House on a unanimous 427-0 vote. [81] Action then shifted to the Senate, which waited for several months before considering it. The full Senate considered the measure on June 30. During those deliberations, Sen. Robert Dole (R-Kan.) introduced an amendment to the bill urging action on provisions unrelated to the Anaktuvuk Pass ATV issue. The bill, with Dole's amendment, passed the Senate that day on a voice vote. [82] That bill's provisions, however, were soon folded into an even larger bill, H.R. 1296, which passed the Senate on May 1, 1996. Four months later, during the waning weeks of the 104th Congress, legislators cobbled together an even more comprehensive bill, H.R. 4236. This bill, called the Omnibus Parks and Public Lands Management Act of 1996, was introduced on September 27, and within the next month it passed both houses of Congress. President Clinton signed the bill on November 12. [83] Twelve years after Anaktuvuk Pass residents and NPS officials began working on the problem, the land exchange was finally implemented. Anaktuvuk Pass residents responded by holding a festive November 14 celebration in the village's community hall. [84]

G. SRC Recommendations: Eligibility Issues

During the 1990s, SRC members and other subsistence users continued to be concerned over several eligibility-related issues. Among them were 1) the consideration of new resident-zone communities, 2) the delineation of resident-zone boundaries, 3) the establishment of a community-wide "roster system," and 4) the imposition of a residency requirement. These four topics will be discussed in the order listed above.

1. New Resident Zone Communities. As noted in Chapters 5 and 6, Alaska's national park units had 49 different resident zone communities at the close of the 1980s; this was the same number that had been listed in the June 1981 subsistence management regulations (see Table 5-1). [85] During the 1980s, SRCs had sent letters to the Interior Secretary recommending that Ugashik, Pilot Point and Northway be considered as new resident zone communities, but each had been rejected on the grounds that the NPS knew of no proven interest in subsistence hunting by residents of those communities.

During the 1990s, these and other communities were considered anew for resident zone status. At Aniakchak, SRC members recognized in 1990 that a logical first step to involve Ugashik and Pilot Point residents was to have them apply for 13.44 permits; given that option, the SRC received no further action for new resident zones. Seven years later, a similar scenario was played out at Denali; the SRC asked the park superintendent for assistance in obtaining resident zone status for Tanana, and in response, the NPS dispatched the park's subsistence coordinator to the community but found no one there interested in obtaining a 13.44 permit. [86]

All other activity pertaining to potential new resident zones occurred at Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. As has been noted in greater detail in the park's subsistence management plan, the SRC responded to the Interior Secretary's denial of eligibility for Northway by resubmitting, in December 1991, a recommendation that was similar in intent to that which it had submitted in August 1985. Seven months later, the Interior Secretary responded to the SRC by noting that "the NPS must first verify that [Northway has] a significant concentration of local rural residents with a history of subsistence use." [87] Four years later, the SRC also recommended the addition of Tetlin and Dot Lake as resident-zone communities, and before long Tanacross, Healy Lake, and Cordova were considered as well. The NPS responded to each of these requests by either 1) studying the situation (support-office staff wrote a 1998 environmental assessment regarding the eligibility of Northway, Tetlin, Tanacross, and Dot Lake), 2) holding a public hearing soliciting interest from townspeople, or 3) asking an agency anthropologist to visit each community and ask residents about local subsistence-harvesting patterns. [88] In time, the NPS found that five villages—Dot Lake, Healy Lake, Northway, Tanacross, and Tetlin—were eligible to be new resident zone communities. As a result, the agency published a proposed rule on the subject in June 2001 and a final rule in February 2002. The rule became effective on March 27, 2002. [89]

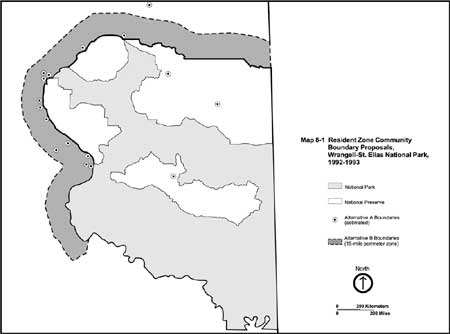

2. Resident Zone Boundaries. As noted in Chapter 6, NPS officials had made some attempts during the 1980s to establish boundaries around the resident zone communities, but their efforts had been only modestly successful. By 1990, in fact, only two resident zone communities had established boundaries, both of which were near Denali. The Wrangell-St. Elias SRC, by contrast, had dug in its heels and stated its refusal to establish any such boundary lines.

This halting progress continued during the 1990s. Communities adjacent to several park areas moved to establish resident zone boundaries, but elsewhere, NPS officials and SRC members skirmished over the issue, resulting in an awkward standoff. At Denali, for example, the park SRC decided in June 1994 to establish boundaries around the two resident-zone communities (Nikolai and Telida) that did not previously have one. [90] And at Gates of the Arctic, the park SRC responded to a request from the Wiseman Community Association by moving, in September 1991, to establish boundaries for Wiseman; the NPS responded to the SRC's proposal the following February by conditionally approving the proposed boundaries. [91]

|

| Karen Wade, Wrangell-St. Elias's superintendent from 1990 to 1994, weighed in on many subsistence issues. A particularly nettlesome issue was that of resident zone community boundaries: whether boundaries should be established, and if so, where they should be located. NPS (AKSO) |