|

ACADIA

Man and Nature Sieur de Monts Publications VII |

|

|

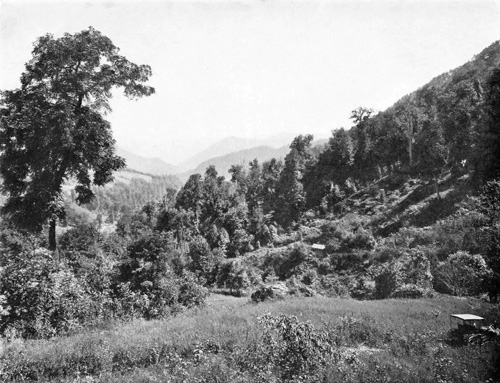

| A beautiful landscape in the Southern Appalachians |

Man and Nature

By GEORGE B. DORR.

A paper written in 1913, when plans now realized for the creation of a national park upon Mount Desert Island were first brought forward.

The question of Public Reservations is of paramount importance in the eastern portion of our country, where we have already got a dense population swiftly created and swiftly growing denser without apparent limit.

Magnificent reservations have been created in the West, with wise prevision; nothing similar, save the recent first establishment of national forests in the Northern and the Southern Appalachians, has yet been undertaken in the East, with its far greater human need, its beautiful scenery, ready accessibility and permanently productive territory.

We are passing into a new phase of human life where men are congregating in vast multitudes, for industrial purposes, for trade and intercourse; the population of the future must inevitably be many times the population of the present, and the need of conserving now, while there is time, pleasant, wholesome breathing-places for these coming multitudes is great. How great, we can with difficulty realize in our country yet so newly occupied and in a period so new of growth and vast industrial change, but what such open spaces in the form of commons have meant to England in the past, the long struggle to prevent their enclosure by the few shows strikingly, and what is lost by their absence in densely peopled regions of China, where every rod of ground is given up to the material struggle for existence, the accounts of all returning travellers tell.

But it is not a question of breathing-spaces and physical well-being only; it goes far beyond that and is deeply concerned with the inner life of men. With Nature in her beauty and freedom shut out from so many lives in these industrial and city-dwelling time, it is going to become—has, indeed, become already—a matter of supreme importance to preserve in their openness, in their unspoiled beauty and the charm of their wildlife, their native trees and plants, their birds and animals, the places where the wealth or significance of these thing is greatest, the places where the influence of Nature will be felt the most or where the life with which she has peopled the world, and man or chance has not destroyed, may be enjoyed and studied at its fullest.

The times are moving fast in the destruction of beautiful and interesting things. The lost opportunity of one year becomes the bitter regret of thinking people in a few years more. Valuable and interesting species of birds, that were still familiar a generation since and that might have added to the delight or wealth of the world forever, have now become extinct—as hopeless of resurrection as if we had known them only in fossil forms. Many a landscape and forest-land that should have remained for ever unspoilt and public in the crowded eastern regions of the future has been ruined needlessly or locked up in private ownership.

|

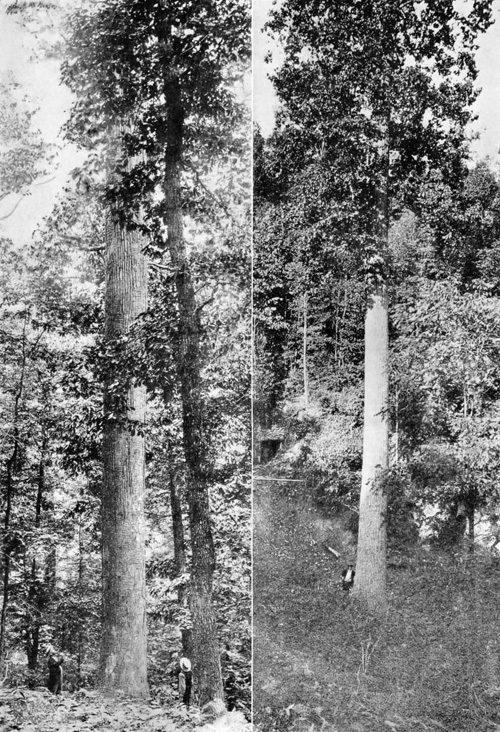

| Giant tulip trees: North Carolina, on the left; Virginia, on the right |

In nothing is conservation needed more than in saving all that is economically possible of the pleasantness and freedom of Nature in regions accessible, even by travel, to the vast, town-dwelling populations of the future; in preserving the features of scientific interest or landscape beauty that widen men's horizon or quicken their imagination. City parks and playgrounds, valuable and necessary as they are, cannot do this, nor can cultivated fields and motor-traversed roads. The bold hilltops and mountain-heights which the ancient Hebrews felt were God-inhabited; the clear springs in Syria over which the Greeks built temples through whose ruined stones the crystal water still comes gushing; the sacred groves of Italy and Druid oaks of Northern Europe, tell a story of the deep influence of such things upon the hearts and lives of men, an influence we cannot afford to lose today in our mechanism-shrunken modern world of immeasurably growing population.

By taking thought in season, little need be sacrificed to secure incalculable benefits in Nature's wilder near-by regions, in her grander landscapes that lie within the reach of busy men; in refreshing forests, not too limited; in picturesque and open downs beside the sea; or along the pleasant, wooded side of streams with unpolluted water. When coal become exhausted, water-power or other form of energy will take its place, but nothing will ever compensate for natural beauty permanently ruined within the narrowing bounds of modern life.

|

| Lakes in the Sieur de Monts national park—Looking north toward the Mainland |

Life will always be a compromise between conflicting needs, but its needs are not material only. Man's future is deeply concerned with recognition of its spiritual side, and if there be anything in the world, next to the opportunity to gain the necessities of life, to meet disease or find the means of education, that should be kept open to right use by all, it is the wholesome freedom of Nature and opportunity for contact with her beauty and many-sided interest in appropriate tracts. The day will ultimately come when to provide such will be felt to one of the most essential duties of the state or greatest privileges of wealthy citizens. For wiser and better gifts than these, to be public heritages forever, it were hard to find. Permanent as few others can be, they will only gain with time, in beauty often and in richness of association always. Changes in science or social organization, altered standards of artistic interest or change in charitable method will not destroy their value.

There are landscapes and tracts of land which for their beauty and exceptional interest—or their close relation to important centers—should be inalienably public, forever free to all. Our metropolitan parks and reservations are a first step in this direction, as are the national parks out West, but with increasing private ownership and rapidly increasing population, the movement is one that will need to go far eventually.

The earth is our common heritage. It is both right and needful that it should be kept widely free in the portions that the homes of men, industry and agriculture do not claim. Personal possession reaches out at widest but a little way, and passes quickly in the present day, gathering about itself little of that greater charm which time alone can give. If men of wealth would spend but a fraction of what they do for themselves alone, with brief result, in making the landscape about them beautiful for the benefit of all in permanent and simple ways, the result would be to give extraordinary interest—of a steadily accumulative kind—to every residential section of the land; and it would tend, besides, to give all men living in or passing through it a sense of personal possession in the landscape instead of injury at exclusion from it, and to give them, too, a freedom of wandering and a beauty by the way which do not lie within the reach of anyone today.

|

| Water lending beauty and refreshment to a Southern Woodland |

And with such gifts would also go the pleasant sense of sharing, of participation in a wholesome joy which each recurrent year would bring afresh. No monument could be a better one to leave behind, no memorial pleasanter—whether for one's self or others—than gifts like these, to be public heritages forever, it were hard to find. Permanent as few others can be, they will only gain with time, in beauty often and in richness of association always. Changes in science or social organization, altered standards of artistic interest or change in charitable method will not destroy their value.

There are landscapes and tracts of land which for their beauty and exceptional interest—or their close relation to important centers—should be inalienably public, forever free to all. Our metropolitan parks and reservations are a first step in this direction, as are the national parks out West, but with increasing private ownership and rapidly increasing population, the movement is one that will need to go far eventually.

The earth is our common heritage. It is both right and needful that it should be kept widely free in the portions that the homes of men, industry and agriculture do not claim. Personal possession reaches out at widest but a little way, and passes quickly in the present day, gathering about itself little of that greater charm which time alone can give. If men of wealth would spend but a fraction of what they do for themselves alone, with brief result, in making the landscape about them beautiful for the benefit of all in permanent and simple ways, the result would be to give extraordinary interest—of a steadily accumulative kind—to every residential section of the land; and it would tend, besides, to give them, all men living in or passing through it a sense of personal possession in the landscape instead of injury at exclusion from it, and to give them, too, a freedom of wondering and a beauty by the way which do not lie within the reach of anyone today.

And with such gifts would also go the pleasant sense of sharing, of participation in a wholesome joy which each recurrent year would bring afresh. No monument could be a better one to leave behind, no memorial pleasanter—whether for one's self or others—than gifts like these that make the earth a happier, a more interesting or delightful place for other men to live upon.

That this movement must grow, no one who has thought upon the matter can doubt—the movement for public parks and open spaces, near or far, not as playgrounds simply but as opportunities for Nature in her deep appeal and various beauty to remain an influence in human life; for places, too, where such features of wild life as may coexist with man can be preserved, and where plant life, whether in forest growths or the infinite detail of flowering plants and lowly forms, may still continue a source of health and happiness in man's environment.

The movement will grow, as all great movements do, because a great truth—man's need for Nature—lies behind it. The essentially important thing is to save now what opportunity we can for its expansion later.

| <<< Previous | Next >>> |

sieur_de_monts/7/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 25-Mar-2016