|

ZION

Plants of Zion National Park |

|

Zion-Bryce Museum Bulletin

Number 1

PLANTS OF ZION NATIONAL PARK

Vegetation and Climate

The vegetation of Zion National Park is an interesting mixture of desert and mountain flora, due to the contrasting kinds of country within the park, which is located on the boundary between the high cool plateaus of Utah and the hot desert of the southwest. Here, at the southern edge of the Markagunt Plateau, the Virgin River (a tributary of the Colorado) has cut many deep canyons that open out on the deserts to the south; so that the park consists of three kinds of country, each with its distinctive climate and vegetation: cool plateaus 6500 to 7500 feet altitude in the north; a small strip of hot desert below 4000 feet altitude in the south; and a network of canyons between, which have an intermediate climate.

The plateaus, including numerous flat-topped peaks and mesas, are covered with chaparral and forests in which yellow pine is the dominant tree, with douglas firs end aspens in moist places. This indicates that they are in what is termed the Transition Zone, or Yellow Pine Belt; in other words, the climate and vegetation is similar to that found at low altitudes in the northern states where there is a transition between hot southern climate and the colder conditions of Canada.

Typical plateau scene in Zion National Park, showing oak chaparral and a

small grove of quaking aspen in front of the belt of yellow pines and

firs, — N.P.S. photo.

In the canyons, between 7000 and 4000 feet altitude, the climate is somewhat warner, usually too warm for yellow pines, but favorable for such trees as Utah junipers and the pinyon pines, which form a sparse pygmy forest on all the dry s1opes and flats between these altitudes. Along stream banks and other moist places in the canyons the firs and aspens of the plateaus are usually replaced by cottonwoods, ashes, and boxelders. This belt of climate and vegetation is termed the Upper Sonoran Zone.

Along the southern border of the park, where the canyons open out upon relatively flat semi-desert country, the pygmy forest gives way to desert chaparral, in which creosote bushes and black brush are the dominant shrubs. This is known as the Lower Sonoran Zone, and although only a few square miles of park territory are within this zone, yet it is important botanically because of the large number of species peculiar to it, and because of the interesting ways in which many of these species survive the extreme heat and drought.

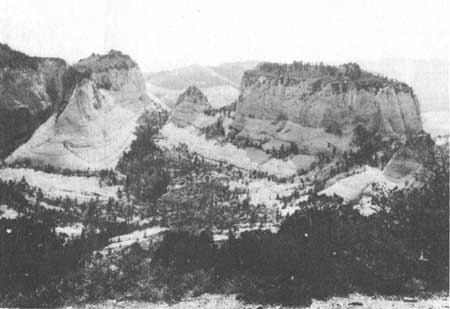

Typical Zion Park scene, showing various vegetation types on the

temperate plateaus, the warm talus slopes and semi-barren rocks, end the

cool narrow canyons. —N.P.S. photo.

These three climatic zones can be easily recognized by any park visitor. Desert shrubs indicate Lower Sonoran Zone, pygmy forest indicates Upper Sonoran Zone, and yellow pines indicate Transition Zone. The vegetation is so naturally divided into these three groups that in this bulletin the distribution of many plants is given simply by zones.

However, one should not think that as soon as he passes above an altitude of 7000 feet on a trail or road, he will abruptly pass from scrub junipers to stately yellow pines. The change is always gradual, and may occur 1000 feet or more above or below the 7000-foot average. In a shaded canyon the climate will be much cooler at 5500 feet than at 6500 feet on a sunny south slope. For example, in going up the West Rim Trail, one finds yellow pines and aspens growing in a shady spot above Scout Lookout at 5600 feet, while at 7200 feet, on the south slope of Horse Pasture Plateau he will pass through groves of pinyon and juniper. The complex system of canyons in Zion causes many such reversals of the normal zonal distribution of plants. In this region the life zone idea should be considered as the basic pattern in which intricate variations have been produced by differences in sunlight, moisture, and soil.

The most noticeable of these variations is to be seen in the bottom of nearly every canyon, where much moisture and shade favor the growth of Transition or even Canadian Zone species no matter what may be the actual altitude. In canyons where water seeps continually from the cliffs there are great "hanging gardens" of ferns and other plants that would normally be found at a much higher altitude. The Narrows is the classic example of this, but dozens of other canyons have the same type of vegetation.

Aside from zonal distribution, the climate produces another entirely different phenomenum—a yearly cycle of blooming periods. The moisture and moderate temperature of spring causes the most varied flower display of the year during March, April and May. In early summer, as the result of a hot drouth period during June, there are only a few species in bloom, mostly night-bloomers. From August to October the late summer thunder storms cause a second flower display nearly equalling that of the spring months.

(Note: Authorities for scientific names have been omitted, in the interest of economy of space. Nomenclature is chiefly according to the "Flora of Utah and Nevada", by Tidestrom. In grasses we have followed "Manual of the Grasses of the United States" by Hitchcock; and in trees, "Check List of the Forest Trees of the United States" by Sudworth.)

One of the many "hanging gardens" in The Narrows, where seepage water in

a cool shaded nook has produced a luxuriant growth of ferns, grasses and

flowers.